Alexander Provan

Programme for the 2016 Benefit Event Honoring Julie Ault

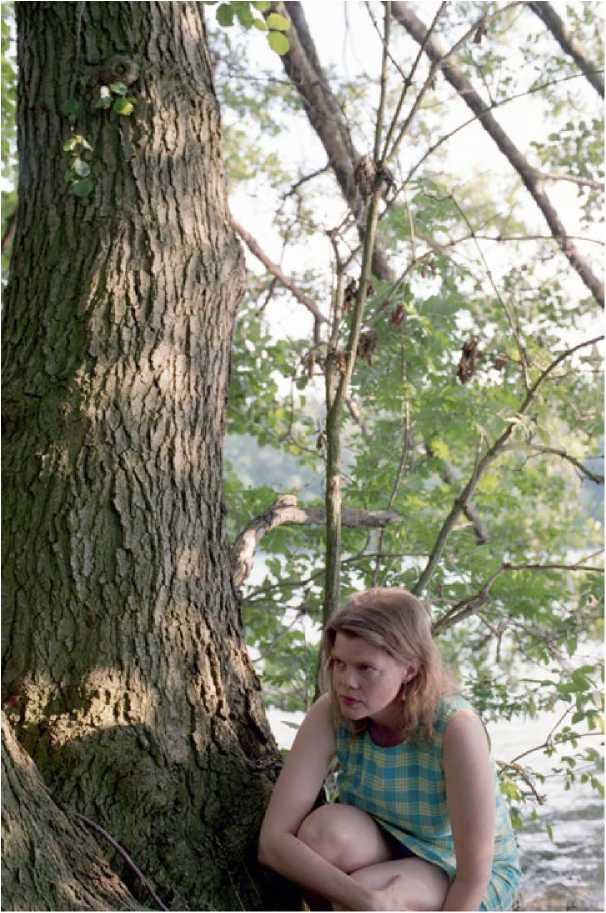

Cover and inside back cover:

Wolfgang Tillmans

Concorde L441-8A, 199Z

Portrait of Julie Ault, May 2010

Courtesy David Zwimer, New York,

Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin,

and Maureen Paley, London

A Benefit for Triple Canopy

Honoring Julie Ault

Jing Fong, 20 Elizabeth Street, New York, NY

November 16,2016

7:00 Cocktail reception

8:00 Dinner: family-style dishes, tea, and dessert

8:15 Welcome by director Peter J. Russo

and Board member Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy

Remarks by poet Cathy Park Hong,

introduced by editorial director Molly Kleiman

A word from Julie Ault

9:00 Final note by Board member Malik Gaines

9:30 Dinner concludes

After-party: drinks and music by DJs Yaeji and BEARCAT

Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy is a curator and writer. She is the curator of contemporary art at the Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. Hernandez was curator of the 9th Mercosul Biennial in Porto Alegre, 2013, and an agent for dOCUMENTA(13) in Kassel, 2012. She previously served as director of the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City. She held curatorial positions at Art in General and Americas Society and sits on the board of directors at both Triple Canopy and Creative Time, all based in New York. “Sanctuary: Andrea Bowers” and “Home: Andrea Aragon,” both part of a series of exhibitions organized by Hernandez, are currently on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Cathy Park Hong is a poet whose latest collection, Engine Empire, was published in 2012 by W. W. Norton. Her other collections include Dance Dance Revolution, chosen by Adrienne Rich for the Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Translating Mo’um. Hong is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. Her poems have been published in Poetry, A Public Space, the Paris Review, McSweeney’s, the Baffler, Boston Review, and the Nation, among other journals. Her writing on politics and her reviews have appeared in the Village Voice, the Guardian, Salon, the Christian Science Monitor, and the New Pork Times Magazine. She is the poetry editor of the New Republic and is an associate professor at Sarah Lawrence College. “Forecasts,” by Hong and artist Adam Sheerer, was included in “Negative Infinity,” the fifteenth issue of Triple Canopy, published in 2011.

Our enormous gratitude to the members of our Benefit Committee, whose kindness and generosity helped make this evening possible.

Honorary Committee

Eileen Cohen* & Michael Cohen, Alex Logsdail*

Patron Committee

Alexandra Economou*, Marian Goodman, Agnes Gund, Hauser & Wirth, Katy Lederer* & Ben Statz, Susanne Vielmetter, Begum Yasar

Support Committee

Marianne Boesky, Matt Brumberg and Ryan Brumberg, Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Muller, David Deitcher, Fairfax Dorn*, Heather Flow, Keith Fox, Gabrielle Giattino*, Barbara Gladstone, Regan Lin Grusy* & Anders Bergstrom, Nicholas Harteau, Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy*, Jim Hodges, Heather Hubbs, Karen Kelly and Barbara Schroder, Prem Krishnamurthy*, Margaret Lee & Oliver Newton, Susan & Harry Meltzer, Fraser D. Mooney*, Cory Nomura, Penny Pilkington and Wendy Osloff, Simon Preston, Steve Pulimood, Andrea Rosen, Jane Rosenblum, Mary Sabbatino, Kate Shepherd*, Kara Vander Weg & Brett Littman*, Thea Westreich Wagner & Ethan Wagner, Jeffrey Weiss*

Event Committee

Noreen Ahmad, Carolyn Alexander & Ted Bonin, Ian Alteveer, Augusto Ar\yao, Artforum, Roland Augustine, Beth Aviv, Alexandra Bowes, Caroline Bourgeois, James Keith Brown & Eric Diefenbach, Isabel Byron, Susan Cahan & Jurgen Bank, Kim Conaty, Gabriella De Ferrari, Katie Dixon & Richard Fleming, Bruce Ferguson, Alexander Ferrando, Michelle Finocchi, Richard Flood, Andrew Francis, Barry Frier, Malik Gaines*, Maia Gianakos, RoseLee Goldberg, Amy Goldrich, Claudia Gould, Joanne Greenbaum, Janice Guy, Michael Hainey*, Jane Hait, Kenan Halabi, Joy Harris, Pati Hertling, Steve Incontro & David Joselit, Hillary Jacobs, Carin Kuoni, Chiswell Langhorne, Barbara London, Isaac Lyles, Christopher Lyon, Kathleen Madden & Paul Frantz, Monica Manzutto & Jose Kuri, Christian Marclay, Jennifer McSweeney, Nicole Mercer, Gregory R. Miller* & Michael Weiner, Jonathan Miller, Roger Mooney & Donald Steele, Barbara & Howard Morse, Liz Mulholland, Philip Munger, Josephine Nash, Brooke Garber Neidich, Jody Oberfelder & Juergen Riehm, Mathieu Paris, Birgit Rathsmann, Charles Renfro, Allison Rodman, James Rondeau & Igor DaCosta, Esther Rosenberg, Natalie Rousso, Carol Salmanson, Jeanette Watson Sanger & Alexander Sanger, Susan Sawyers, Susan & Kent Seelig, Thor Shannon, Julia Sherman & Adam Katz, Yancey Strickler, Margaret Sundell, Julia Trotta & Davide Balula, Jasmin Tsou, Rachel Uffner, Scott Cameron Weaver, Allison Weisberg & Peter Barker-Huelster, Sam Wilson, Candace Worth, Alex Zachary, Bettina Zerza

Benefit Committee list current as of November 2,2016. Asterisks indicate current or emeritus members of Triple Canopy’s Board of Directors.

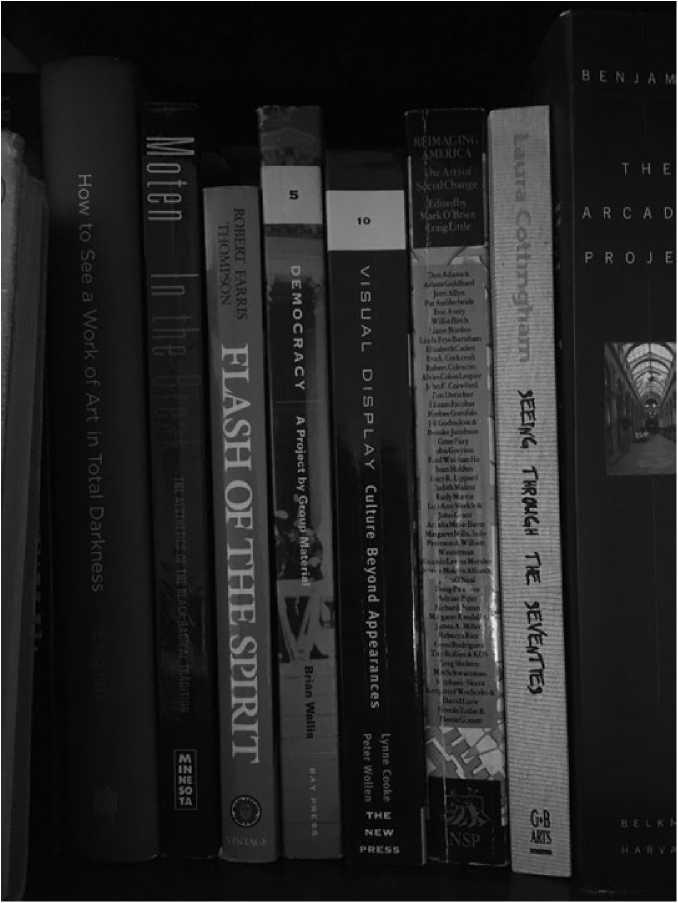

Details from Alejandro Cesarco, A Printed Portrait of Julie Ault, 2012

Sadie Benning

Psychic Portrait #5,2016

Aqua resin, acrylic, wood, photographs, and digital image 19.5" x 15"

Signed and dated by the artist

From Psychic Portraits, a series of six works created for the occasion of Triple Canopy’s 2016 benefit

Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter

Los Angeles Projects

For Psychic Portraits, Sadie Benning created six unique works based on artists and friends held in common with Ault. Benning, who has explored the relationship between painting and sculpture in recent years, here deepens an engagement with the photographic and filmic media of earlier works. Yet Benning’s handling of materials in Psychic Portraits borrows equally from all these art forms, combining materials and styles that do not conventionally merge. Each portrait features a dominant image that Benning disrupts by embedding digital snapshots, reproductions of found photographs, and other pictures onto its surface. The resulting construction is seemingly bound together by irregularities, complicating the viewer’s ability to make easy associations, especially concerning popular representations of gender and sexuality. With Psychic Portraits, Benning challenges stylistic norms and proves the infinite malleability of transitional identities and artistic genres alike.

Benning’s work is held in many museum collections and was recently included in “Greater New York,” MoMA PSI; “Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age,” Museum Brandhorst, Munich and MuMOK, Vienna; “The Carnegie International,” Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; and “Tell It to My Heart: Collected by Julie Ault,” Kunstmuseum Basel and Artists Space. This fall, Benning mounted solo exhibitions at Kaufmann Repetto, Milan; the Renaissance Society, Chicago; and Air de Paris, Paris.

Special thanks to Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects for its generous support.

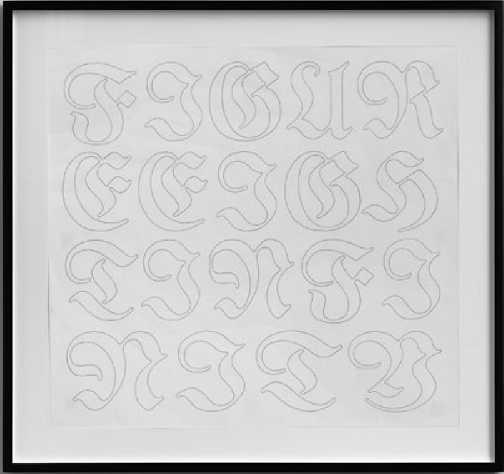

Danh Vo

Figure Eight Infinity, 2016

Pencil on Ingres d’Arches

20.5" x 22.5" (drawing); 23.5" x 24.25" x 1.5" (framed)

Certificate signed and dated by the artist

From a series of seven works created on the occasion of Triple Canopy’s 2016 benefit

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

For this series, Vo and Ault devised a series of psychic messages for seven individuals. Vo and Ault solicited the help of Elaine Ault, Julie’s mother, who is a psychic medium—a person who tunes in to spiritual energy to channel timely information and messages. Elaine relayed a sequence of symbolic phrases, such as “Figure Eight Infinity” or “Seven Gold Butterflies,” for each of the seven subjects, whose identities remain concealed. Phung Vo, Danh’s father and frequent collaborator, then rendered these texts by hand in a calligraphic blackletter script. As in many of Vos past works, the materialization of clairvoyant messages in this series speaks to the ways in which meaning (whether or not decipherable) is embedded in everyday objects, and the ways in which they constitute or represent us, even as they are displaced, fragmented, appropriated, and passed from hand to hand.

Danh Vos lauded series of sculptures We the people consists of full-scale facsimiles of New York’s Statue of Liberty; it was initiated in 2010 and continues to be exhibited around the world. Vos work has recently been presented at Museo Jumex, Mexico City; Nottingham Contemporary, UK; and The Kitchen, New York (all 2014). Vb was the recipient of the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize in 2012. He is represented by Marian Goodman Gallery in New York and London, where “Homosapiens” was on view in 2015.

Special thanks to Marian Goodman Gallery for its generous support.

As an artist, writer, and curator, Julie Ault has developed a model of creative research that engages with an ever growing circle of artists, writers, scholars, activists, and communities. These collaborations have led to countless exhibitions, books, and other projects that reveal pathways for artists whose work exceeds the gallery space or the printed page. On the occasion of its 2016 benefit, Triple Canopy invited a number of contributors and friends to consider a prompt inspired by her work: “The Internet has made the tracing of relationships between disparate cultural materials into a seemingly everyday maneuver. Which strategies might now be effective in rewriting dominant historical narratives, whether despite or because of the proliferation of new technologies?”

Here, thirty-five contributors—Fareed Armaly, Doug Ashford, James Benning, Jonathan Berger, Antonio Sergio Bessa, Nayland Blake, David Breslin, Andrianna Campbell, Moyra Davey, David Deitcher, Thomas Eggerer, Hu Fang, Juan Gaitan, Lia Gangitano, bell hooks, Roni Horn, Steffani Jemison, Branden Joseph, Isaac Julien & Mark Nash, Ted Kaczynski, Prem Krishnamurthy, Rachel Kushner, Zoe Leonard, Lauren Mackler, Lara Mimosa Montes, Christopher Muller, Lawrence Rinder, Tim Rollins, Andrea Rosen, Sarah Schulman, Felicity Scott, Matthew Shen Goodman, Jason Simon, and Marvin J. Taylor— present responses to this prompt, drawing upon their collaborative experiences, or affinities, with Ault and her work. Additionally, Jim Hodges contributed the insert in this booklet; Martin Beck created “earthquake,” a tote bag designed with Ault; and Andrew Durbin generously scribed our fortune cookie fortunes.

FAREED ARMALY

Last July 15 at the venerable British Library, Viv Albertine (guitaristsongwriter for punk icons the Slits) took issue with a wall panel in the exhibition “Punk 1976-78” that read: “Groups such as Sex Pistols, The Clash and Buzzcocks stimulated a nationwide wave of grassroots creativity, sparking a vital cultural legacy that endures to the present day.” Marker in hand, Albertine crossed through the veritable UK punk pantheon and added her former band, as well as X-Ray Spex and Siouxsie & the Banshees, signing “(What about the women!! Viv Albertine).” Images of her action upon the panel were duly amplified through social media outlets and, perhaps unsurprisingly, Albertine’s corrective inscription managed to avoid removal. As such, it allowed us to observe how an exhibition wall panel in the British Library could embody two disparate readings—institutional and interventional—as narrative entanglement of what is/is not on display. Unable to visually merge composed museum type with indecorous handwriting, the panel oscillated between presumptive authority and object of scrutiny.

I chose to also write “upon” this defaced exhibition panel, where “Punk” and museum meet as contemporary history, partly because of the ways “no future” resonates within the notion of an archival imperative to preserve the future as open-ended, as future to come. It offers an institutional narrative cleaved (meaning both split apart or caused to become one, adhere) by a disarmingly direct, reminiscently punk gesture. I want to consider this exhibition panel, speculatively, as an interface situated between two types of public Commons pertaining to vast repositories and databases: the British Library and the Internet. The former, a sovereign representative and regulatory institution, is more inclined to conservative history writing, as Albertine’s inscription attests. The latter, a networked regulatory technological formulation, registers her gesture as media event while inevitably accelerating, thus abstracting, the criticality of the panel’s meaning and content. This particular in-between space provokes me to return and restate Albertine’s inscription, now as: “What about the institutions?” In regard to the prompt, shouldn’t such questions of “technology proliferation,” “strategies of rewriting,” and creative practices emerge alongside and intertwined with the urgency of future critical frameworks: new, effective, and critical mandates of arts/culture institutions?

DOUG ASHFORD

JAMES BENNING

On New Year’s Day 2011, Julie and I crafted a letter together. Julie had learned about my Two Cabins project and thought it was pertinent to contact Theodore John Kaczynski. Near the end of January we received a response.

TED KACZYNSKI

To

JULIE AULTJanuary 18,2011

Dear Ms. Ault,

Thank you for your interesting letter dated January 1, 2011. My focus is almost exclusively on a practical problem (to put it succinctly), how to get rid of the technoindustrial system before it gets rid of us. I can’t find much time to spend on such issues as the value of solitude, privacy, or wilderness, except to the extent that these issues are relevant to the practical problem. (They are relevant to a point; teaching people the value of solitude or of wilderness, for example, helps to alienate them from the values of the technoindustrial system...)

...As for Thoreau, he’s okay, but I’ve never had any particular admiration for him. You’ll find much better nature writing (in my opinion) in Joseph Wood Krutch, The Desert Year (top-notch!). I can also recommend highly a book by Tom Neale, Alone on My Island (the title is not a figure of speech). Of great interest is Alexander Selkirk, who was the inspiration for Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. An account of Selkirk’s adventures was published back in the 18th century, and it exists in a modern (like, mid-twentieth century) reprint. You’ll also find some eloquent passages about wilderness and solitude in Calvin Rutstrum, Paradise Below Zero and in Horace Kephart’s Book of Camping and Woodcraft. Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders is of considerable interest too...

...THEORDORE JOHN KACZYNSKI

00475-046

U.S. PENITENTIARY MAX

P.O.BOX 8500

FLORENCE CO 81226-8500

JONATHAN BERGER

I first became aware of Julie Ault’s work when I was a teenager in ACT UP, around 1996, working alongside Karen Ramspacher, who had collaborated with her as a member of Group Material.

Ault’s work and way of being in the world became a model for me of what it means to have no model, to work with total freedom coupled with a profound sense of responsibility, to see beauty and ethics as both essential and inseparable, to be accountable to history while remaining unbound by it, to view dissent as generative, to believe that you can and should operate in any role and use any approach that allows you to do your work in the most meaningful way possible, and to truly assess and reject the confines of a given field in which you are working.

All of this changed my conception of what art could be and how it could be made. It established for me an understanding of the role of the artist as being rooted in a true and radical independence, and one which is as integral as it is valuable in the context of collaboration.

As an adult, who went on to become an artist, I remain inspired by Julie Ault’s work, though now I also learn from the ways in which she has maintained her unique variety of independence over time, allowing it to change how she engages with the world in response to how the world engages with her.

ANTONIO SERGIO BESSA

Notes for a Landscape (in the manner of Martin Wong)

—for Julie Ault

here in the small, deep, sandy valley, closed in on all sides by barren slopes

The city in which a thousand small theatres would have provided an endless multicolored representation of

The main entrance—the only entrance for convicts, their visitors, and the staff—was crowned by an escutcheon representing Liberty, Justice, and, between the two, the sovereign power of government. Liberty wore a mobcap and carried a pike. Government was the federal Eagle holding an olive branch and armed with hunting arrows. Justice was conventional; blinded, vaguely erotic in her clinging robes and armed with a headsman’s sword. The bas-relief was bronze, but black these days—as black as unpolished anthracite or onyx.

“My every effort here is a sentence of condemnation against me

NAYLAND BLAKE

Here’s what I believe:

I first met Julie in the late ’80s in Buffalo, at a gathering for the National Association of Artists’ Organizations. It was an event that led to connections, collaborations, and an informal network of young artists who were working through and with nonprofit artist spaces as curators, critics, and creators. Within the work of opening new vistas for social engagement and new methods of interrogating identity, there was play and joyful recognition.

I remember her poise and precision.

We traded work. From me she received a collection of paperbacks boxed in plexiglass. In return she gave me this: A square photograph, framed in thin black wood. Of the surface of the moon. Small craters and rubble stretch to the horizon, which is slightly curved. There is a second small black-and-white photograph, tucked into the corner of the frame, the way you would when you had something around the house you wanted to keep looking at, but didn’t have a more formal place to put it. It shows a reclining woman on a stage being looked at by men. The camera is behind her so we see their faces, not hers. Her back is rendered white by the flash or the stage lighting. These two photographs have been made to cohabitate by a calm quick gesture, made to answer, interrupt, complete each other. Intimacy and the cosmos, both airless. Inside and out, one taken in a moment replete with display and desire, one requiring immense human effort to capture. Is the moon what they see when they look at her? Is the entire show meant to be taking place in lunar isolation?

I’ve lived with that piece since I received it, looking at it for years. But for more than a decade it has been in my closet unseen, a victim of transcontinental moving, so that even now I ransack my memory to make sure that I haven’t substituted some other photographs for the ones I remember. I don’t want a connection tarnished by an overstuffed mind. But then I always flutter in the presence of the utterly cool.

DAVID BRESLIN

Julie Ault: ARTH 568 Fall 2013,Williams College

Julie Ault (b. 1957) is an artist best known for her work with Group Material, a New York-based collaborative active in politically engaged exhibition making in the 1980s and 1990s. In addition to her work with Group Material, her own individual practice, and collaborative projects with Martin Beck, Ault’s practice also consists of her functioning as a writer, curator, and editor. She has written extensively on—and often in collaboration with—a number of artists and filmmakers including, among others, Sister Corita Kent, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Cerith Wyn Evans, James Benning, and Danh Vb. As opposed to the monographic seminar or exhibition that examines, contextualizes, and theorizes the oeuvre of a single artist, this class will study the constellation of practices in the galaxy of Ault’s artistic and intellectual project. While this seminar’s moves from singularity to plurality and from production to framing are familiar—and still necessary, as we will explore—poststructuralist and postmodern gestures, we will not abandon Ault to the position of mere cipher. Though we will not attempt to unify the disparate projects under any Aultian umbrella, our analyses necessarily will force us to ask how the artist—or the art historian, the critic, the writer, you, I—chooses the subjects of study that partially reveal how she conceives of herself as a subject. Though our primary task will be to read critically about—and look closely at the work of—the artists and collaborative practices mentioned above, we also will pay attention to topics including: feminism, countercultures, the function of translation, the role of biography in writing art history, the history of collaborative practice, the critique of the artist, and the critique of the institutions of art. Thinking by way of Julie Ault, we both will consider the personal nature of all critical endeavors and the heterogeneity of practices, theories, and concerns that can be organized under any unstable proper name. Finally, and pertaining to the changing contexts of contemporary art and theoretical production after 1968, we will take seriously Walt Whitman’s famous lines: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

ANDRIANNA CAMPBELL

I remember before Matthew Connors and I went to Cuba for Frieze, we had a pitch before the New York Times Magazine. We had one photograph (taken years before by a Cuban friend) that we were using to pitch a story; they wanted more photographs of where we were going and images to support their possible investment and future publication of the story. We couldn’t find photographs of remote regions on the Internet, and they intimated that their disinterest in supporting the project stemmed from a lack of images, despite an initial flurry of excitement. We didn’t have images mainly because Cubans did not have open Internet access and had not yet subscribed to the global project of photographing and tagging every precinct within their purview. WiFi access had only become available a few months before we landed in Havana. Dan Fox at Frieze was willing to take a chance on a story that had a bit of mystery to it, as the publication world must have been before Google and the World Wide Web. In a similar manner, when I started doing research for my dissertation topic on Norman Lewis, there were few images of his work online. Everyone seemed to think that because you couldn’t find his work online or even in a searchable format on museum websites that there must have been only a smattering of extant work. Ruth Fine and I later uncovered hundreds of paintings and thousands of drawings in private collections around the world. These are but a few personal examples of what many of us are aware of, the way in which the search engine promises us access to a world beyond our borders, but often manages only to promote dominant narratives, the nadir of our desires, and escalates that which is popular despite and sometimes because of its vacuity.

More than ever, we have to be wary of confirmation bias. We all want to be right, but as a scholar I am most interested in what I can’t find and when and why I am wrong. These moments of conflict, of contrast, and (for me) of infuriating humiliation need to be affirmed. Besides training our students and audiences to embrace skepticism as an imperative strategy, visualization technologies could also be important tools for this new age of knowledge transference. For instance, the artist Alex Dodge once showed me a prototype for software he designed for Getty that made search engine results navigable in a charted format. Designed to show results in dot distribution mapping, the software allowed one to quickly see search result outliers, as they dangled far away from the clusters of top hits. Rather than page scrolls away, you could immediately grasp the field. What was a bulkier set of results, what were mis-hits, and what information was coming from primarily unconfirmed sources? It was all there. Perhaps it is naive to think it could matter, but I often find my students more visually savvy than verbally so. Also, they are far more capable of conflating the two. I see them translating long emoji-laden verbo-visual-conversations with confidence. Perhaps the Internet with its merging of the disparate and displaced is at its best seen as a paratactic technology—capable of placing fragmentary results side by side in order to imply a narrative that can only be fully supplemented and confirmed offline. Thus like Julie Ault’s collecting strategies and akin to her constellation of texts, archival materials, artifacts, and artwork, the tenuousness of networks becomes readily apparent. If, in our online screen interface, we were to concretize a means to embrace the discontinuous as well as the continuous, it could serve to undermine those narratives that are most ascendant and indicate where our offline searches should survey.

DAVID DEITCHER

Early in 1991, I took a panorama picture of a stylish, resolute, but not noticeably happy-looking Julie, posed wearing a black suede zip-up jacket and big shades in front of what Wiki informs me should be called the “Sleeping Beauty Castle” at Disneyland. One glimpse at that picture was all Julie needed to liken her look to that of a “mafia princess.” I like living with this picture in its long, plexiglass frame, which I keep on a bookshelf in my study. It stands in front of books by Freud, Lacan, D. W. Winnicott, Adam Phillips, etc. Coincidence? Not according to any of them! I still like my encounters with that picture in part because it can still summon the glee with which Julie then sometimes responded to the mere mention of “the happiest place on earth.” She and I had taken a day to drive to Anaheim for a visit to the so-called Magic Kingdom (my first and presumably my last) during her brief visit to see me and other friends in LA while I was teaching at CalArts.That was little more than two years after Group Material completed its multidimensional Democracy project for Dia; and after we lost our friend Bill Olander to AIDS. It was the same year Julie decamped from Johnson Street in Brooklyn to a one-bedroom apartment of her own on Bleecker and Mercer Streets. That was a turning point in all of our lives; perhaps a tipping point in Julie’s. Neither for the first nor for the last time, she was deep in process, open as always to new experiences, and more than amenable to change. She was becoming the fiercely independent yet deeply engaged, and engaging, altogether awesome Dr. Julie whom we know, learn much from, and love. She gave me a tiny, timeworn picture of a much younger and more vulnerable-looking Julie—“little Julie” (her term), which I’ve kept tucked into the upper right-hand corner of the plexi-framed “mafia princess” ever since. The two pictures complement each other, hinting in their overly simple ways at the totality and complexity of the restlessly evolving, fearless woman we all have the pleasure of honoring tonight.

MOYRA DAVEY

THOMAS EGGERER

Earlier this year Julie sent me a surprise gift: It was one out of a series of collages her mother Elaine had made decades ago, probably in the ’70s or early ’80s.

The collage assembles a group of magazine cutouts of female models radiating with self-assured poise. I am intrigued by the formal qualities of the piece: the particular color choice and the way all elements are arranged to generate a coherent surface.

As far as I know, Julie’s mom has been a housewife in rural Maine, raising kids like my own mother. I do not think that she had any particular involvement in visual art other than a general curiosity.

What was her motivation to select and cut out these images of women?

What inspired her to make something beautiful and aesthetically pleasing out of these rather banal clippings?

Models, of course, are classic Pop and Appropriation Art iconography. But what distinguishes Elaine’s collage is its totally un-ironic sincerity. I do not think the collage is a comment on or a feminist critique of media representation of women.

I rather believe the collage above all expresses a desire to connect to and identify with an imaginary space of glamour and urban finesse.

In combining these pictures of women, which are generally authored by men, Elaine is creating a Ladies’ club all of her own choice, reflecting her idea of understated sophistication.

Elaine never considered showing this collage in public. It was stored away in a bureau drawer, but perhaps it was instrumental in sparking Julie’s interest in archives and their policies.

HU FANG

So, herefrom

So, herefrom, we begin to speak to each other, just like any stories that don’t have a beginning or an end. Was it in a Chinese garden nearly deserted? Perhaps we met at the end of that weed-paved path, or it was on that placid stone bridge, whereas I remember our conversation took place in the kitchen of the garden—sounds a bit strange, yet indeed, it’s not only a kitchen, but also a pharmacy, where plants handily accessible (Chinese mugwort, basil, honeysuckle, chrysanthemum) all could be made up into prescriptions that cure our bodies.

It seems that we always met in a kitchen, doesn’t it? In Berlin, a winter, at another friend’s kitchen, pots and bowls were hanging from the ceiling, as if instruments ready to perform for life. Outside the window, the city streets were drowned by the ruthless snow. Perhaps we should be happy that we met this time in the warmth of the South, perhaps it was due to the moisture infused in the air, once I saw you, I started to imagine the days you spent living in the mountains. Having been out of correspondence for some time, every time I received your letter, I had to be reminded of Kaczynski’s typewriter, words can be weapons, as well as sympathy.

At this moment, I regain my thoughts, I regain my thoughts, hands grasping your letters, we hold tightly in our hands the words of each other—the place where our encounters were made possible, and so, herefrom, we begin to speak to each other, just like any stories that don’t have a beginning or an end.

JUAN GAITÁN

Julie Ault

2015: met in Mexico City

2015: met again in New York

2015: met again in Venice—or was it the other way around?

2015: met in Mexico City, again

2016: So far a sad year on this front, devoid of meetings with Julie Ault

This list provides limited proof, but perhaps our friendship is one of odd numbers

Julie Ault is an odd number

I’d like to think I’m an odd number (we’d have to ask Julie Ault)

Can this friendship be described in 351 words? I’m already at ninety-eight, as the hyphen makes two words count as one. Can one write ninetyeight? Seems not. Spellcheck has just underlined it in red, in a wavy red line. One hundred and twenty-nine. Let’s use the remaining two hundred and sixteen more wisely.

I met Julie Ault and was amazed because it is rare to find a mind these days, at least in the art world (one is tempted to stop here, but that would be a bad joke), a mind that still represents the kind of American thought that inspired one to believe in the idea of the individual as a political and a social project. To say it as a slogan that I have the idea existed—I heard it from my teachers several times, but never knew where it came from—“Individuals without individualism.” Maybe one should say “Individuals against individualism.”

What does this mean? I want to say that it means or suggests the affirmation of the individual in relation to others, friendship being the noblest form. A political project based on friendship, on thinking together, with each other but also against one another, towards a common truth that is forever elusive. I am lucky that I can consider Julie Ault a friend.

On mentors.

“For the Record.” Julie Ault opens her introduction to Alternative Art New York (an art worker’s spiritual guidebook) by noting:

“Existing documentation of New York City’s highly influential alternative art culture of the 1970s and 1980s is ephemeral, and its circulation is restricted.”

Julie changed that with her exhibition and publication Alternative Art New York. She then further traced such actions with the editing of Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material from the “file cabinets, closets, bookshelves, and under the couch(es)” of her and other group members’ apartments.

Beyond these indelible contributions to all of us, Julie’s influence on me personally has spanned Public Interventions (1993); shoe shopping; Research Architecture (2001); and the correct pharmaceuticals for public speaking, memorials versus awards.

Getting to know those close to her heart through her work—Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Sister Corita, Jochen Klein, Frank Wagner, Martin Wong—has been a consistent privilege throughout my adult life.

Sabrina Locks notes in “Tracking AIDS Timeline” that “An exhibition can function, however provisionally, intentionally or not, as a prescriptive presentation of history, or, as in the case qIAIDS Timeline, as a call to amend its course.”

Emphasis mine. Because Julie has, in many ways, amended the course of history for many of us, re-emphasizing those histories deemed inconsequential. Life-work and friendship, collaboration and closeness, history and having a future—all are leveled into an “unconfined horizon” of “overdrive advocacy” through her work. These are Julie’s words for describing activist-curator Frank Wagner, which also describe her particular impact.

Julie makes reference to Liberace’s mirrors, creating hallways of shimmering ghosts. But I am reminded of a pilgrimage taken to Paradise, Nevada, to visit “the world’s largest cubic zirconia” at the Liberace Museum. Often referenced as a symbol of the falsehood of American dreams, it now seems to me a refracted mirror repository of alterity. Julie opens these, too, in her exhibitions, writings, improvised exchanges, performances of archives, and collections of love.

bell hooks

“As we critically imagine new ways to think and write about visual art, as we make spaces for dialogue across boundaries, we engage a process of cultural transformation that will ultimately create a revolution in vision.” (Art on My Mind, 1995)

As artist, critical thinker, and all-around fun girl, Julie Ault shows remarkable generosity of spirit both in her artistic vision and her ongoing curatorial work.

RONI HORN

Excerpt from “Moving Water: The Flow of Roni Horn,” 2013.

roni horn: But I remember having a discussion with a psychologist about how depressed people can’t see the future. Sometimes I don’t have a future.

What I have is probability. I see what my past has been—you don’t have that when you’re younger. When you’re younger, the degree of uncertainty is massive, and it gets a little bit more contained as you get older just by virtue of having options whisked away from you by age and time and energy. But I still feel the enormous presence of doubt and uncertainty in everything I do.

julie ault: Well, there’s a kind of indifference, if not aversion, to security and definition, which I have a strong affinity with.

I don’t think it’s really a choice for you, it’s a vital orientation. Not naming yourself or allowing yourself or your work to be categorized means staking out a marginal position in culture as well as sacrificing degrees of prominence and legibility in the world.

horn: There’s a new word for what you’re describing, unfortunately. It’s outlier.

One of the other things that’s happened now is the extraordinary amount of information that we have access to all of a sudden, all the time, and everywhere—it sucks out energy just knowing it. So it takes more energy in a certain sense just to find the stream you want to swim in, just to find that thing within this infinity of information. It presents a kind of false complexity. But I can’t ignore it. I have to find a way to negotiate it.

It’s the rate of change, too. Maybe it’s good to have navigational or organizational elements that help you frame the space, or whatever you’re working with. But there’s also the sense of that space changing, so when you come back to it, let’s say in a couple of years, that space is gone. It’s not recognizable. So, the acceleration of time is something I’m aware of, and I don’t mean that as somebody getting older. Even for the young now, the sense of time is incredibly speedy and, strangely, perpetually brief. ault: There’s anxiety as well as excitement in figuring out new navigational modes for working with what is virtually a new system relative to when you and I came of age. The accelerated tempo of research combined with information abundance and open access certainly changes previously held notions of expertise, and of subjectivity. Subjectivity is more and more prone to unraveling.

horn: Subjectivity has become a luxury; it’s a luxury to have your own space in your own time now. That’s a huge thing. I like to keep my feet in the water, moving water, so I definitely want to know what’s going on. The way I work is to be actively engaged with the options out there. I don’t want the work process to solidify around a certain technique I developed twenty years ago. And in effect, it wouldn’t happen to me because the open end of my view or vision is so wide. That’s what keeps the anxiety and uncertainty in play. I don’t associate that with a negative, but I’m more aware of it now than I was—but then it was somehow more subjective.

STEFFANI JEMISON

BRANDEN JOSEPH

Over the course of the past few years, Julie Ault has taken to lining the passageways of her exhibition spaces with mirrors. A potentially effective means of testing for art-loving vampires (who would pass through the thresholds unreflected), the installations recall precedents from such art-historical figures as Robert Smithson or Robert Morris. Julie’s avowed reference, however, is the flamboyant, candelabra-loving pianist Liberace, whose mirror-lined hallways she discovered in a real estate agent’s video of one of the entertainer’s Las Vegas homes. Precise and visually captivating, yet nearly disappearing into their environments, Julie’s mirrored passages seem indicative of her working process. For while Liberace almost certainly affixed mirrors for the purpose of basking in his own reflected glory, Julie deploys them both to mark and deflect from her own artistic presence within exhibitions she dedicates to the work of others. Refraction—as the phenomenon of deflecting the focus (of light, radio waves, etc.) from a single point throughout a surrounding milieu—might be understood as emblematic of collectivity, an essential aspect of all of Julie’s art and thinking. As in a mirror, it proves nearly impossible to focus on her work without its simultaneously bringing someone or something else into view. Her oeuvre thus proves indissociable from others’: Group Material (of course), David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Sister Corita Kent, Cerith Wyn Evans, Martin Beck, James Benning, Ted Kaczynski, Liberace, all those included in the exhibition “Macho Man: Tell It to My Heart,” and more. This fact seems appropriate for an artist whose foremost subject is nothing other than history as a collective endeavor, memory as the means, medium, and media of artistic practice.

ISAAC JULIEN & MARK NASH

Hi Julie,

Congratulations on being honored by Triple Canopy. Well deserved!

We love this picture of you and Isaac in NYC. We remember that red coat from evenings in Bleecker Street, intense discussions of art, culture, and politics in various SoHo venues, particularly with miss bell. We thoroughly enjoyed seeing the “Macho Man” show in Lisbon a few years ago, being reminded of such important artists as Felix (Gonzalez-Torres) and Tony Feher whom we first saw with you.

You were one of the first to develop a multidisciplinary practice— artist, curator, critic, publisher, and designer. You paid great attention to the way works are installed and interact with graphic support; indeed the scenography became the work in some instances. You made use of the whole wall surface in exhibition spaces—echoing the salon hang of 100 years before but with a new modern and post-modern focus on de-hierarchising space. AIDS figured prominently in your early work with Group Material, and you continued to explore the potential of that minimal aesthetic, echoing the simplicity and fragility of contemporary work such as that of Felix.

Your installations always provide such intense aesthetic pleasure, which in turn focuses the viewer’s attention on the subject matter. The whole space of installation is rendered with such care that it becomes merged with the ‘content’ in fact. Brecht’s concept of a theatre of pleasure which is also a theatre of instruction was completely true of your work.

Full speed for the next decade, Much love, Isaac and Mark

TED KACZYNSKI

For a long time I’ve wondered why my friendship and our “dialogue” (as she calls it) have seemed important to Julie Ault. But when I received a letter from Triple Canopy inviting me to write something in her praise, I noticed a reference in the “prompt” to Julie’s “efforts to engage in dialogue with an ever growing constellation of artists, writers, scholars, activists ...,” and I had a flash of insight: Julie is a collector, impelled by the same mania that drives collectors of stamps, coins, autographs, butterflies or Chinese porcelains—except that instead of collecting physical objects Julie collects friends with whom to have dialogues. And I’m an item in her collection!

PREM KRISHNAMURTHY

Searching in my archived emails, I found the first electronic message I ever received from Julie Ault, on July 1,2010. Amazing how simple such an act of memory now seems. You don’t need to sort through desktop files, piles of paper, or overstuffed hanging folders anymore. Yet with this ease and smoothness of interface, you lose the inherent friction that remembering used to embody. Nowadays we often forget that although “searching” may appear objective, the results you find on the other end are anything but.

The subjective act of searching, of archiving, of collecting, of arranging, is something that I had long admired from afar in Julie’s work as a writer, curator, artist, and editor. Her early projects with Group Material highlight the role of the exhibition as an inherently social medium: exhibitions can become spaces where people, ideas, and objects encounter each other on relatively equal footing. The AIDS Timeline (1989) offered a new social and cultural history for a political issue, while embedding the artists’ own personal and emotional positions into the installation.

I was too young to see it in person—the exhibition opened exactly on my twelfth birthday—but, going through its archive at the Berkeley Art Museum many years later, I was impressed by GM’s collaborative and inclusive process of making the show. To me, it represented a way of sorting through the world and all its unruly stuff that still acknowledged one’s own role in the mess.

Julie herself is certainly part of the world’s mess, in the best possible manner. I think of her as a special kind of cultural producer: one who comments critically and poetically on the circumstances around her, while still remaining an active participant in them. My impression is that she’s fully present in whatever’s at hand—whether an exhibition, a conversation, or a party. Assembling collections of friends and colleagues in a way that is fluid, playful, productive, and fun, Julie maintains deeply felt relationships of camaraderie and labor. Like the groups of materials in her exhibitions and publications, such social dynamics represent trajectories, dialogues, and rejoinders, moving as a constellation around you. I know I’m lucky to be part of it.

RACHEL KUSHNER

WE ALMOST BLANKETED THE COUNTRY (for Julie)

We almost blanketed the country. Especially late at night.

I suppose they thought I was just the build for it because I was long and skinny for my age (and still am) and in any case I didn’t mind it much, to tell you the truth, because running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police.

We have this country that’s so rich. You live in California and try to walk on it you get your ass shot off. Is it ours really? How much of it is ours?

Some can go to factories or villages just to look around; this may be called “looking at the flowers on horseback” and is better than doing nothing at all. Others can stay for a few months, conducting investigations and making friends; this may be called “dismounting to look at the flowers.” Still others can stay and live there for a considerable time, say, two or three years or even longer; this may be called “settling down.”

See that place up there? It’s called “Adult Living.” Sounds pretty erotic. I guess we have something to look forward to.

I get my own room here, my meals, laundry, and my money, too. Funny thing about these nurses. They all look good in clean white uniforms and nice white shoes, but they look like hell when they dress up to go out. I’ve never known one yet who knew how to wear clothes on a date. But when the clothes come off, they’re women, and that’s the main thing with me. Did you see that nurse I was talking to in the hall?

Consider the girls in a factory—never alone, hardly in their dreams.

Once we know the number one, we believe that we know the number two, because one plus one equals two. We forget that first we must know the meaning ofplus.

“Well, and now let’s end our speeches and go to his memorial dinner. Don’t be disturbed that we’ll be eating pancakes. It’s an ancient, eternal thing, and there’s good in that, too,” laughed Alyosha. “Well, let’s go! And we go like this now, hand in hand.”

“And eternally so, all our lives hand in hand!”

In order: Roy Acuff, Alan Sillitoe, Philip Levine, Mao Tse Tung, exchange between James Benning and Dick Hebdige, Charles Willeford, Henry David Thoreau, Jean-Luc Godard, Fyodor Dostoevsky

ZOE LEONARD

LAUREN MACKLER

Terms of “Service” and a definition of our “Terms.”

A CENTO (sometimes known as the “Baghdad Pact”) is a “Poem” made entirely of quotations. The effect is multifold: by culling from a range of sources—poetry, yes, but also legislators and astrologers, sociologists and artists, each with their own “Facts” and science—“Our” poet creates a cohort of absent writers, as well as new conditions for each phrase. By rule, the sources may or may not be cited. This remains at the discretion of the aggregator, evidently not the aggregated. In a case in which it is not cited, the element of content (“The Phrase,” “The Source”) takes on new “Characteristics”; it becomes contingent on, as well as a “Property” of, its new context. It is severed from its genealogical ties, sometimes—I would go so far as to say—challenging its original “Intent.” Its definition, now unfixed, is duplicitous. The commons, one could argue, are at the cost of common ground.

Good evening. How nice of you all to corned

Let’s begin by saying that we are living through a very dangerous time.2

The truth, I would like to say here, is as follows. But I can’t.3 He wrote, he said, with a sense of responsibility 4 What does knowing feel like. What does your knowing feel liked “Love” triangles, like other forms of romantic geometry, are nothing new...6

Our “Terms” make up the entire agreement between “Tou” and “Us.”7

In standard usage, quotation marks indicate a conventional distance between speaker and utterance. Words in quotation marks are spoken in a different voiced Alternatively; words may be placed in quotation in order to alert the reader to the malleability of their meaning. In this latter sense, quotation marks may be used to isolate a word whose (possibly new) “Definition” can be found in the surrounding sentence, in context.

As is the case in many contracts, as is the case of this particular “Contract.”

This piece of writing is indebted to Anne Carson’s transcript of'Albertine, James Baldwin’s “we,” Renata Adler’s punctuation, Edward Albee’s obituary, Litia Perta’s experiential definition of knowing, Anthony Lane’s criticism, Google, for its contracts, and Aaron Kunin for his Cold Genius.

LARA MIMOSA MONTES

“Some Semblance of Together”

could we / be together / in real time / last week / as I livestreamed / a protest /1 asked myself is this the window / or is this the world /lam made / nervous / by my inability / to give / as much as other people / give / aka the people I was / watching / people I did not know / why / didn’t I / know them / did the fact that I had the choice / to livestream the protest / somehow / relieve me / from the burden of attending / and being / with the people I needed / to know most /1 shared the link to the livestream with others / in an attempt to connect / maybe you / were already there / so when you returned home / to see / my attempt / to include you / you thought / it redundant / but in the off chance / that maybe you were / like me / also watching / from behind a screen / so you could say / later / what you saw / what you thought / you saw /1 wondered / could we / inhabit this moment / together / will we ever / reconcile / the distance between where you are / standing / and where I am not / at what point / do we get to say /1 remember / and actually believe it / is there a way of being / there / that matters / more / than other ways of being / there / or is this irrelevant / given the world / we live in / and our shared blind spots / we have them / but how can we use them / those blind spots / these windows / our bodies / to help us find one another / in the present / in the dark / at the same place / at the same time

CHRISTOPHER MULLER

Julie Ault is most definitely one of my favorite people and somebody whom I admire and to whom I look up immensely, looking up as to fantasize some strange reasoning into decisions this person makes, to catch up later or just enjoy where that goes. On different occasions of working together with Julie, I was amazed to see how every aspect of an undertaking is considered, not least through her very unique life planning that seems to enable an unparalleled dedication. It was an actual delight to see how, in producing a book or an exhibition with Julie, methods or conventions would immediately transform into modes of transporting content—content in its most diverse manifestations, without being controlling in any boring sense, always keeping more than one side visible (not only the light or the noise), like the mirrored passageways that Julie developed inspired by Liberace that are perfectly simple and complicated vehicles to bring you into the next room, and through which, in looking back and forth, you see things in different constellations depending on your point of view.

LAWRENCE RINDER

Way before people were googling this and that, accessing online databases, juggling a dozen simultaneous “windows,” and joining virtual communities, Julie could put it all together by sheer force of will. She—along with her many partners in collective activism—uncovered lost histories and created new social realities through the radical juxtaposition of images and ideas, research unchecked by disciplinary boundaries and a desire to open an ever- wider space for creativity, conversation, and even conflict. She has a visceral ability to appreciate contradictions and to absorb seemingly irreconcilable contrasts as an integral element of democratic exchange. So, if we use the Internet well, we can perhaps be a bit more like Julie.

In 1989, just before the Internet was commonly available, Julie came out to Berkeley with Doug Ashford, Karen Ramspacher, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres to create the AIDS Timeline. Thinking back, it’s hard to understand how they did all the research without the Internet, because they seemed to spend all of their time sitting around the pool. But they did, somehow. And their exhibition overturned every curatorial convention of the day. Their selection of works ignored hierarchies of taste (yet everything looked great); they mixed art and non-art (which somehow elevated the impact of both); and they integrated the didactic, or informational, dimension of the project into its essential structure (i.e., a timeline). Julie and her partners in Group Material invented a new genre. It doesn’t have a name but it’s a cross between an artwork and an exhibition, between propaganda and a poem, between a town meeting and a novel.

How does the Internet itself extend Julie’s radical insight into curatorial and artistic form? There are countless ways, of course, but my own proposal would be for a movement of people’s novelists to embark on a project of rewriting world history. With the world’s archives now widely available and virtually every image ever made at our fingertips, I’d love to see a global movement of excavation and imagining. It’s time to unearth our lost narratives, illuminate connections, imagine alternate realities, call out villains, and honor the angels.

TIM ROLLINS

Ault—a Thesaurus (from the American Heritage Dictionary, Fourth Edition)

abacus, abaft, abeam, aberration, abiding, ability, ablaze, ablution, abolish, A-bomb, aborning, above, about-face, aboveboard, abracadabra, abreast, absolute, absorbent, abundant, Arcadia, accelerando, accelerator, acceptor, accessible, acclamation, accommodating, accompanist, accomplice, accomplish, accord, accordion, acculturation, accumulate, ace, acknowledge, acorn, across-the-board, act, acute, adagio, adamant, advanced, adventurer, adversarial, advisory, advocate, acrobatic, affinity, affirmative, a float, aflutter, afterglow ... Agape.

ANDREA ROSEN

Excerpt from a conversation with Triple Canopy director Peter J. Russo, October 2016.

Peter J. Russo: This morning, I read an interview between you and Julie, published on the occasion of her doctoral exhibition Ever Ephemeral (Signal, Malmo, 2011). In the conversation, you mainly discuss how you and Julie decided to widely disperse the books from Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s library to his friends.

I imagine this had some bearing, if only distantly, on your approach to the recently published boxed set of books chronicling the gallery’s history which has the quality of a small library in and of itself. I’m guessing there was a moment during production when someone on staff or you yourself thought this could just as well be a Web archive. But then you thought, No, the book is actually the best technology for this historical project.

andrea rosen: It’s interesting that you raise the importance of the choice of media to me, this is certainly one way Julie’s thinking has influenced me. The collection is intended to be a physical manifestation of the gallery. Even though the individual volumes are numbered, they lack a hierarchy. You don’t even really have to open them to recognize the diversity of programming. There’s a relationship between the physicality of the books and the physical experience of exhibition and object-making. Whereas with the vastness of the Internet, we often view one image and then quickly look elsewhere. These are two very different mediums with which to coach viewers into thinking about the openness of something.

russo: It occurred to me that the books may not remain together as a set, that they might find their own way out into the world individually. Each has a colophon and credits, so perhaps there was even some anticipation that the set would eventually be broken up?

rosen: We printed extra copies of each book in different quantities based on the likelihood of which ones would be handed- out individually. This also goes back to your question about Felix’s library and whether objects in a collection retain the aura of the whole when they part. I’m sure Julie and I have talked about how dispersion can have an additive effect on aura.

russo: How does this aura apply to the way the gallery operates? I was thinking about the role of the gallerist, particularly the person whose name is on the door, and the act of balancing a personal vision, however defined, the collective and individual desires of the artists that make up the gallery program, and simply what is being made at the moment, or what is useful to a certain community at that time.

rosen: There’s a great dichotomy in my practice. On one hand, I’m interested in the power of experience. On the other, I take the gallery’s responsibility to creating permanence, and potentially history, seriously. While I’m interested in artists who will contribute to art history in the long run, the power of transience is also interesting when collectors negate works they’ve purchased but are no longer valued in the same way. Yet the collector couldn’t have moved along to other works without collecting the objects in question.

I think we undervalue the ethereal, those things that deeply affect and change us but don’t provide a physical record. I’m interested in this relationship to the writing of history. While I’m an extremely loyal person, I allow for the weight of these connections to come and go because genius doesn’t always work at the same pace.

More and more, I think it’s the gallerist’s responsibility to think about how this model of excellence and openness is upheld. While I think that Julie and I share a love of the visceral, we seem to also need faith in objects to remind us we’ve changed, and to remind us of progression and our responsibilities [laughter]. And thinking about Julie, the root of what she has always done in terms of curating is asking, “How do you juxtapose information?” And what she does, and why it’s so relevant to current thinking about technology, is that she represents this sort of “trust piece” within a structure that breeds responsibility. How do you give up control by creating a foundation that essentially trusts people to continue to mutate a model so that it continually improves, that it becomes better instead of worse? Julie’s structure is about trusting that there is more to be gained out of more and more freedom.

SARAH SCHULMAN

Julie’s desire to connect with others, to connect others to each other, to build relationships and exchange perceptions, is a gorgeous human impulse that is both facilitated and obstructed by our contemporary options. Like all technological advances, our current modes are subject to the character and weaknesses of their users. Those of us living in shame and blame use these technologies to avoid the changing of self-concept that is inherent in true interactivity with others. We cling to the one-dimensionality of the message: only my expression matters. Blocking, hiding behind email, cold shouldering are truly destructive and divisive choices that speak to our worst impulses: isolation, self-aggrandizement, and the refusal to understand relationship as the centerpiece of healing. However, when we truly want expansion, are open to the growth that comes from the recognition of difference, and feel an urgency to not waste our lives in prisons we choose to live in, then the new technologies provide endless opportunities to take in other people’s experiences, to fully humanize others in ways that illuminate ourselves. For example, if I did not rely on Facebook and Twitter communications from Palestine, I would have no reasonable information source to counter dehumanizing misinformation, both ignorant and deliberate. Reading, following, and asking allow me to expand my consciousness and understand better paths towards transformative and responsible action. Similarly, seeing photos of people in their lives, hearing about their triumphs and defeats, seeing how we all react to ongoing collective events, gives others more dimension in my imagination, and makes me deeper and more comprehending of this temporary, one, and singular life that I have here with others.

FELICITY SCOTT

“Meeting Up”

Solitude, as Julie Ault argues in (FC) Two Cabins by JB, “does not just happen now, nor did it in Thoreau’s time. It has to be created.” Under the title “Freedom Club” she articulates, with beautiful precision, the multitudinous, if unexpected, affinities and connections attending the politics of seclusion of Henry David Thoreau and Theodore (Ted) Kaczynski, both of whose remote cabins had recently been “reconstructed” by James Benning in the Sierra Nevada, only a year apart. “Solitariness is at once environmental and internal,” she continues, reminding us of the recursive and complex structure of interrelationships between a subject and her milieu. “As much as solitude implies privacy and tranquility,” Julie concludes of its paradoxically active character, “it also involves withdrawal and segregation. Remove from the mediating presence of others reorganizes the architecture of the psyche, producing a space prioritized by consciousness of oneself. Finding and losing oneself ad infinitum. A one-to-one relationship with place or object transpires—geometrically different from the attention-diverting triangulation that happens when another is present.”

I first received an email from Julie on March 1,2006, shortly after I agreed to write for her upcoming show with Martin Beck at Vienna’s Secession. They invited me to speak in the context of the exhibition, quite literally to “extend the dialog” between my practice and theirs “into the exhibition space and its temporality.” The next month we corresponded about “meeting up,” which finally took place in Silver Lake in May, Julie departing from the “peace and quiet,” if not quite solitude, of Joshua Tree to come into town, to make another connection, mediate another geometry (certainly for me). Inverting her reading of solitude we are reminded that the constellations “of artists, writers, scholars, activists and communities” Julie engages in dialog do not just happen. They have to be created. Marked by an ethics and politics of opening out onto others, Julie’s

constellations—and the collections, dialogs, relations, spaces, geometries, psyches and practices to which they give rise—leave us productively questioning where any outside or exterior might begin, while acting as invitations to a space we can’t quite characterize as an inside. Indeed, they produce a space prioritized by consciousness not just of oneself but of others. At once centering and radically decentering, Julie’s constellations recall the fantastic indeterminacy and reversals at play in Georges Canguilhem’s understanding of relationships between an organism and its milieu. “The milieu on which the organism depends,” he suggested, refusing a singular determinism in favor of complex refractions, “is structured and organized by the organism itself.”

MATTHEW SHEN GOODMAN

The Internet doesn’t trace relationships as much as institute them. These are variably as weak as a broken link whose content you can infer but not verify, and as strong as an email leak. Rewriting dominant historical narratives on the Internet is then always a future-facing action, one of institution—which is an obvious truth of historical writing, because who could write entirely for the past?

The Internet doesn’t institute relationships, people do.

(I don’t know if I believe that in the age of the algorithm, but I’m not sure what that comprises. What does it mean to believe yourself when you say things like that? Does my credit score determine my news? Thankful for Adblocker.) The amount of respect you have for the Internet might then depend on the amount of respect you have for people.

A cartoon of a cat that’s studying to become a dentist because he said he would on his blog. Per cat, “If I make a promise on the Internet, you can be DAMN sure I’m gonna keep it. I got mad respect for the Internet.”

You obviously shouldn’t have that much respect for the Internet, but it might be interesting to ensure the statements made therein. (Claim another’s statement as your own if you haven’t made one.) Insist on whichever history you would like: Yakub made the white man; Zerzanite anti-Whiggism; various claims about Benghazi, the Citadel, vaccines. Make a strong claim. Try to make it true.

A few years ago, I interviewed Julie about her “Macho Man” show at Artists Space (for the Internet). She was kind enough to describe what we saw. I wrote something nearly devoid of content: a well-worn index of what was there (specific works by specific people), tied to a temporal event (the exhibition). I made a weak claim, a broken link that worked. The Internet doesn’t institute relationships as much as trace them. Julie, wonderfully, does both, traces a strong claim.

JASON SIMON

I first met Julie at the Clocktower gallery of PSI, the top floor of 108 Leonard Street, during weekly discussions, presentations, and screenings conducted under the moniker Parasite. The group would continue functioning beyond our scheduled gatherings, and so email was suggested as a way to continue talking. This was not then normal: email was new, and its rules, methods, and behaviors were being negotiated as we spoke. I even used the term train wreck to describe that unknown, the email, anticipating digitally reduced group-face-time (being together was actually the how and why of it, I felt then, and know now). As it turned out, email was OK, more or less reliable, and Julie and I continued to meet when we could, despite and because of everyone’s everyday technological maneuvers.

Much more recently, I had a cosmic encounter with Julie’s mom, Elaine, in Lewiston, Maine. I was there for just a day this fall and recognized her at first by her terrifically ageless fuchsia hair. We were both heading for coffee at Lewiston’s only sidewalk cafe.

“Hummingbird Jason?” Yes to her mnemonic! Few people are less hummingbird like than I am, but I am forever associated with that creature thanks to Elaine’s help years ago, when she interpreted some events for me in which a hummingbird figured.

Elaine and I both experienced this meeting as a major coincidence because we had both had Julie, and even each other, on our minds just then. “The universe works that way sometimes,” she said.

Yes, it does, especially when Julie is in the mix. In order to intervene on the status quo of history and offer meaningful alternatives to dominant cultural forces, you have to have a good idea of how the universe works sometimes. Julie navigates by enthusiasms, Elaine by talismans. Seeing where we connect to what has come before, and how we might affect what can come after, are the shared specialties of mother and daughter messengers.

Strategies are based on mishap. But the talismans of enthusiasm are as good a set of signposts as we might hope for. Better, even.

MARVIN J. TAYLOR

Processing the Past

Julie Ault and I first met in February 2005 at a College Art Association panel called the “Artists Spaces Archives Project: Buried Treasure” in Atlanta. Julie was there because of her book Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985 and her politically and archivally engaged art practice. I was there because I was collecting the archives of artists spaces for the Fales Library Downtown Collection at New York University. As Julie began to talk, I knew instantly that we would become colleagues and friends. Shortly after this meeting, Julie came to talk to me about the Group Material Archive. She and Doug Ashford were interested in placing it at Fales. I was keen to have the records. Then Julie made a proposal I couldn’t refuse: She asked if I could provide space for her to organize the papers for us as a time-based art piece. She would have set hours when she worked on the archive and visitors could come talk with and watch her organize the collection. I loved the idea. Why not foreground the performative aspects of archives via an artist organizing an archive? We utilized our seminar room for the piece. Julie organized the papers over the next few months. This was the beginning of many collaborations with Julie. I soon learned that to know Julie is to collaborate with her and be brought into a group of artists who work together on projects that are bigger than the output of one “artistic genius.” No artist has thought so thoroughly and deeply about archives and art as Julie Ault. I’m honored to call her a friend.

Acknowledgements

Triple Canopy extends a special thanks to the many artists and writers whose contributions made this benefit event an incredible success long before dinner was served, including Sadie Benning and Danh Vo, as well as all our contributors for this publication. We wish to thank Wolfgang Tillmans for this program’s cover art, and Alejandro Cesarco for his portrait of Julie Ault. Andrew Durbin generously scribed our fortune cookie fortunes. Our tote bag, earthquake, was designed by Julie Ault and Martin Beckwith Triple Canopy.

Triple Canopy also thanks the galleries, studio staff, and fabricators who helped make the artwork editions possible, including Elaine Ault, Phung Vo, and Stefan Pederson and Marta Lusena at Danh Vos studio; Rose Lord and Marian Goodman at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Ariel Lauren Pittman and Susanne Vielmetter at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

We’re also grateful to Laura Cadena, Gianni de Falco, Maya Harakawa, Dina Khatib, Stephon Lawrence, and Ariana Perez-Castells for assisting with tonight’s event.

Finally, we wish to thank Claudia Leo and her staff at Jing Fong Restaurant for accommodating us.

With generous support from:

All images courtesy of the artists and writers unless otherwise stated. Triple Canopy is grateful to the many photographers whose images are contained herein.

About the Magazine

Triple Canopy is a magazine based in New York. Since 2007, Triple Canopy has advanced a model for publication that encompasses digital works of art and literature, public conversations, exhibitions, and books. This model hinges on the development of publishing systems that incorporate networked forms of production and circulation. Working closely with artists, writers, technologists, and designers, Triple Canopy produces projects that demand considered reading and viewing. Triple Canopy resists the atomization of culture and, through sustained inquiry and creative research, strives to enrich the public sphere. Triple Canopy is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization. Triple Canopy is a member of Common Practice New York and has been certified by W.A.G.E.

Support

We gratefully acknowledge our Board of Directors, Publishers Circle members, donors to our campaign for 264 Canal Street, and the following foundations for their generous support: AG Foundation; Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; Brown Foundation, Inc. of Houston; Fifth Floor Foundation; Fundacion Jumex; The Greenwich Collection, Ltd.; Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; Lambent Foundation/Fund of Tides Foundation; National Endowment for the Arts; New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; New York Council for the Humanities; New York State Council on the Arts; and the Orphiflamme Foundation.

Credits

Editor

Alexander Provan

Director

Peter J. Russo

Board of Directors

Eileen Cohen

Fairfax Dorn

Alexandra Economou

Malik Gaines

Gabrielle Giattino

Regan Lin Grusy

Michael Hainey

Sofia Hernandez, Chong Cuy

Prem Krishnamurthy

Katy Lederer

Alex Logsdail

Gregory R. Miller

Fraser D. Mooney

Kate Shepherd

Lynne Tillman

Jeffrey Weiss

Creative Director

Caleb Waldorf

Editorial Director

Molly Kleiman

Managing Editor

Bidita Choudhury

Assistant Director

Momo Ishiguro

Senior Editors

Matthew Shen Goodman, Emily Wang

Contributing Editors

Jose Leon Cerrillo, Colby Chamberlain, Lizzie Feidelson, Sam Frank, Lara Mimosa Montes, Sarah Resnick, William S. Smith, Hannah Whitaker, C. Spencer Yeh

Emeritus

Cory Arcangel

Martina Batan

Christine Burgin

Sean Elwood

Wendy Goldberg

Julia Joern

Brett Littman

Selig D. Sacks

Designer

Franklin Vandiver

Lead Developer

Seth Erickson

Front-end Developer

Maxwell Simmer

Technology Advisor

Adam Florin

Production Associate

Gerardo Madera

Copy Editors

Abraham Adams, Emily Votruba, Valerie Werder

Video Producer

Jessica Lee

Editorial Fellow

Maya Harakawa

Interns

Laura Cadena, Gianni de Falco, Hayden Hard, Dina Khatib

Publisher

Triple Canopy

264 Canal Street, 3W

New York, NY 10013

+1 347 529 5182

canopycanopycanopy.com

Apppendix

Text read from first set of images

an orderly view or encapsulation of debated events and meanings is to some extent a revision of events whereby conflicts and contradictions are ultimately resolved, at least in their representation.

The dangers of taking pleasure in the past and the benefits of remembering in order to reinvent arc not clearly posted. There is the risk of peddling nostalgia, of getting lost and/or paralyzed in emotionally inflected territory in which recreation of the past obscures and replaces (or displaces) the present. To aid critical understanding of past specificities, and their effect in the present, it seems more productive to consider loose continuums of production than to provide a form of periodization as punctuation.

245

ostalgia or romantic revisionism . distance (or closeness) to assess gains am .itique.

I'm reluctant to use the word history. It sounds so academic, and implies closure, but this exhibition 1 have organized, Cultural Economics, is nevertheless a histories project, a pieced-together alternative reading of significant art production in still-recent contexts. Histories are always elusive. Hard data can only take us so far. Without voices there is an absence of shape and tone. My investigation in and around the subject has resulted in countless enlightening conversations in which personal convictions, desires, and judgments surfaced, often with mixed and forceful emotions propelling the discussion. What is recalled and emphasized, of course, reflects and reveals individual and collective agendas, pastlense and still playing out.

The very word ‘alternative" produces endless -guments. It's provocative and meaningless, and

■‘sts simultaneously an opening up and a r’ Naming oneself alternative set-

- r TCj. Ia J

iiiucncan west, <»<.».

6e-

The methodological centrality of the personal carries through his complete oeuvre. He has commented: "It’s not hard for me to tell things about myself personally that’s the easy part. The hard part about making personal work is not to make it one man's problem—not to make a film that just refers to my own grief. Who cares about that? I want people to be able to enter the film through their own lives ... But by myself being open I think they can be open to themselves. That's what I think a personal film has to do—has to show a trust but then it has to become more meaningful than what that story is about. It has to be bigger."6*

Benning's films invite us to enter into di’ ■'*' fbe world through private -

h rema. laid bao.

"If you cot. (1984) to Des one way the ground, but u same film.”'”

The indepe once said. “It cnce' mean still a nr what ’ sc-

zu sehen iff, wurde von de>here and now You don't need to know

air jede Arbeit unbelastet una

more then what you see. ft's all here, (insert

Moment. Acme auf jeder Dcta

artist s voice: “You walk into the room t

nt die emziee Gelevenheit, die unquestioning. You take responsibility for

Ktmfteiwtum tn dieten Rdume

being there. In the end I am not interested

prdzise arrangiert veneinijn zu

in what the viewer knows about my inten-

Arheiten bier und ietzl. Du In

tion or identity l am trying to make the

siemt. Es iff ailef vorhanden. ( meaning of the work and one’s experience

den

of it the same.“)u Take your time. Move

Raum bedingungdos. M

antwortung dafur, da» man

through the show from one direction and , ,

mien nient, was dcr Rerracht

double back through and see it all again m

meinc Identitat wcils. Ich bci

reverse. Look closely and then from a dts-

Bcdeutung der Arbeir und ih

fence. Change your position Walk around

werden. )'• Lats dir Zeit. Gen

the work Be in the work There is no ideal

t en dir einvcfchlagenen Weg it

perspective. Look from one room into the

neh dir die Arbeiten noth eini next to where other works beckon. Relish

an. aetrachte de zuern aus dei

the sightlines. Turn around and see where

you came from Watch others looking.

Entfernung. Verandere deii

_ _ tirgib dien in die Arbeit binein

Eavesdrop. See how (he works clarify one

filickr ivn einem Raum in det

another. Absorb the bukd-up of experience. .

aufitch aupnerksam morn want to give an account of if. Yet it is this intimate dimension with which disparate material research reconciles.

Firsthand knowledge is a privilege yet it also causes dilemmas, [s privately obtained knowledge best kept private or can it justifiably be communal? For instance, I may think certain information speaks directly to why a feature of a work of art is the way it is or speaks to what catalyzed a series of works. But does such speculative revelation have productive public application, could it expand the understandings of Fdix’s work? Or would it fix meanings - which the artist himself was unwilling to do - at the expense of viewers' processes? Is there a responsibility to pass on this knowledge? Or will memories fade and firsthand information along with them?