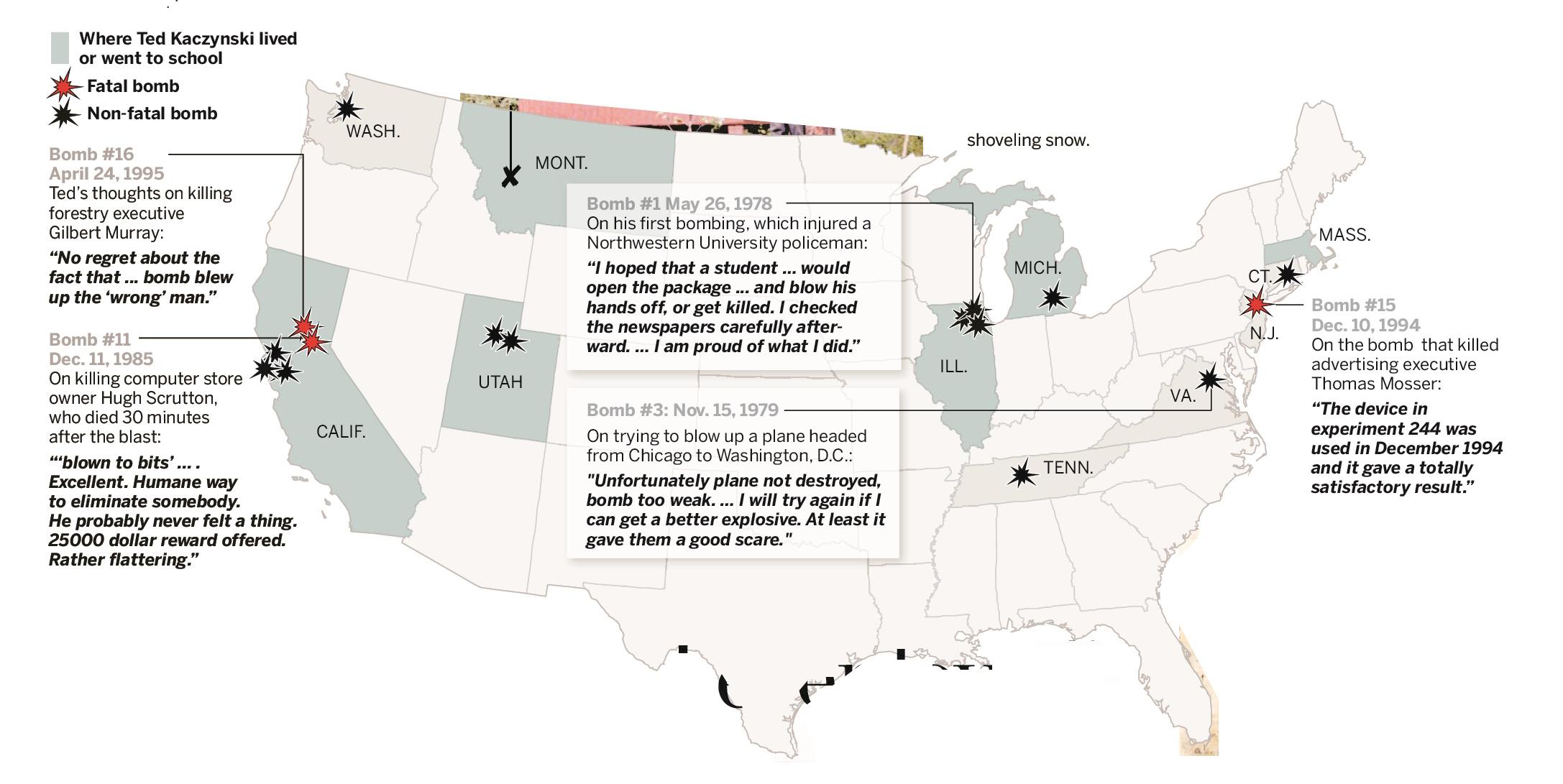

Timeline: The bombings, according to Ted

THE BOMBINGS, IN TED’S WORDS

The FBI called Ted Kaczynski the Unabomber because he started by targeting universities and the airline industry. Over nearly 18 years, he killed three people and injured 30 more. He marked each of his 16 attacks with commentary in journal entries that eventually would help build the government's case against him. Selected excerpts below:

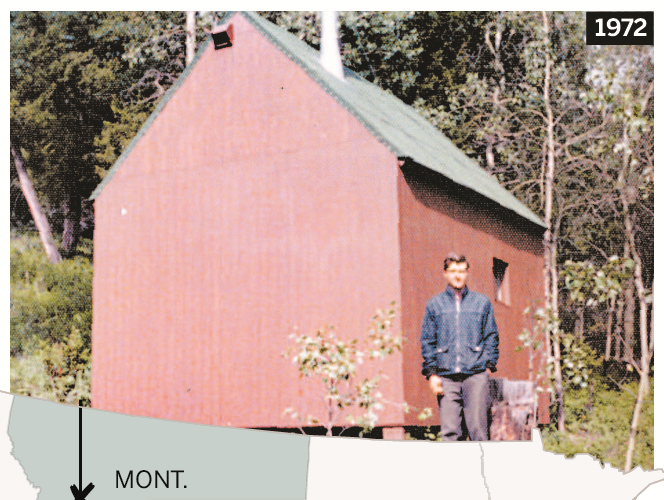

TED’S LIFE IN MONTANA

Ted's cabin in the wilderness lacked electricity and running water. He made his own candles and soap and grew his own food. He traveled mostly by bicycle.

Contraryto initial media reports, Kaczynski was not a complete recluse: He played cards with neighbors and frequented the local library (preferring German classics in German), where he helped on occasion, painting and shoveling snow.

Visit chicagotribune.com/unabomber

Go online to see 50 years of Kaczynski family photos, video of Gary Wright at his bombing site, audio interviews with Ted's mom, Ted's handwritten letters and journals, and his comments on each bombing.

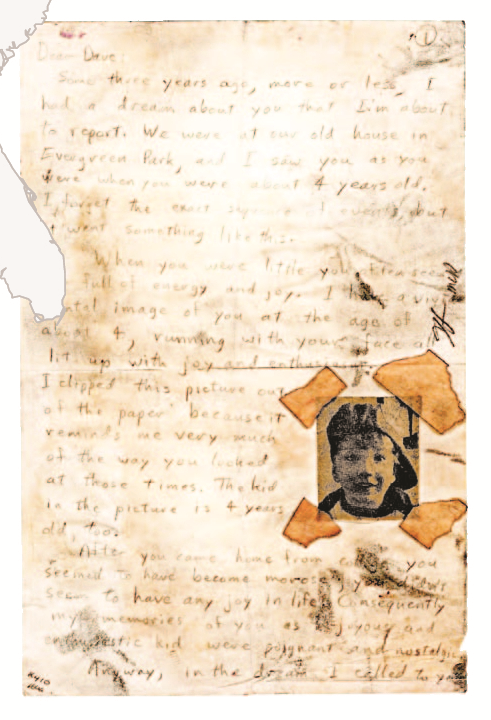

3. ‘The only person I ever loved’

Ted and Dave Kaczynski spent most of their adult lives far apart, but their letters tell a story of two siblings constantly trying to understand and protect one another.

“I have a vivid mental image of you at the age of about 4, running with your face all lit up with joy and enthusiasm,” Ted wrote in 1984.

Taped to it was a newspaper photograph of a smiling young boy who reminded him of Dave.

In their extensive correspondence, they debated philosophy and psychology. Ted helped Dave learn Spanish grammar. When Ted attacked their parents, Dave defended them.

Ted wrote in one letter that if something ever happened to him, he wanted Dave to know that he was “the only person I ever loved.”

Settling outside the small town of Lincoln, Mont., in the early 1970s, Ted plunged himself into self-imposed isolation. The choice surprised his parents but not his brother. Given the ethos of the time, Dave said, Ted’s “dropping out seemed like almost a heroic thing.”

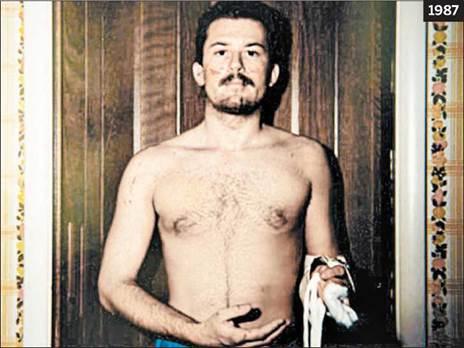

At various times in their lives, both men lived “off the grid,” without electricity, without shaving. For months out of every year, from 1983 to 1989, Dave lived in southwest Texas—first in a tent, then a dugout he carved in the desert floor and, finally, a one-room cabin.

Both immersed themselves in writing, Ted in his journal, Dave in fiction. But Dave periodically returned to Chicago to work and live with his parents, while Ted’s Montana retreat only seemed to fuel his rage.

It also brought out the protective older brother in him. At one point Ted described a dream in which Dave’s friends appeared as demons and took Dave to a place of unspeakable torment.

“He said he would kill them in order to keep them from taking me,” Dave remembers. He didn’t think of it as anything but a fever dream revealing Ted’s innermost fear: that Dave would abandon him.

1986: DAVE’S LIFE IN TEXAS

Dave followed Ted's example to live remotely, doing so part time in southwest Texas, pursuing a writer's life. He also pondered technology, seeing it as a barrier to a more authentic relationship with nature.

1984

In a letter to Dave, Ted taped a newspaper photo of a smiling boy that reminded him of his brother:

“I thought of the fact thatyou were now enjoying the freedom and beauty of the desert, and thisgreatly comforted me. ...soyou see what kind of feelings I have aboutyou, and how much I valueyou-in spite of our differences.”

FBI fingerprinting dust coats the letter.

4. He heard a click

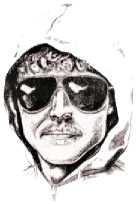

Gary Wright never saw the man in the parking lot, but his secretary did. She noticed him through the rear window of the Wright family computer company in Salt Lake City. Behind a pair of aviator sunglasses, his face was expressionless, thin, with a reddish flush and rough-looking complexion, she would later tell investigators.

His hands, whiter than his face, had long, thin fingers. His fingernails, she noticed, were clean. Dressed in a gray hooded sweat shirt, he knelt and placed something in the parking lot, just a few feet from where she stood.

Arriving for work on that February day in 1987, Wright noticed the object: a nail-studded piece of lumber. In retrospect, he thought, the nails should have served as a warning. They seemed unnaturally shiny, jutting from the scrap of wood.

But he didn’t want anyone to puncture a tire or a child to get hurt. Students walked through his parking lot every day.

Gary bent down. As he picked up the wood, he heard a click.

He didn’t hear the explosion. A single nail shot up through Gary’s chin, piercing his lips and ricocheting off his sunglasses, barely missing his left eye.

The blast liquefied nails and razor blades from the bomb, turning them into corkscrew-shaped shrapnel that tore into Gary’s body, searing shut one artery and severing a nerve in his left arm.

The explosion flung Gary back 22 feet as power lines above him convulsed in a wave pattern. Debris and duct tape spiraled down from the sky like confetti.

GARY WRIGHT’S RECOVERY

HIS INJURIES: He underwent plastic surgery to fix cuts in his face. It took three operations to restore use of his arm and hand, which for two years he kept in a sling that awkwardly rested on his head to reduce pressure on a nerve bundle.

THE STRESS: With the Unabomber at large, Gary lived in a gray uncertainty that strained him and his family. When strange packages arrived at their doorstep, Gary says he and his wife threw rocks at them, half expecting another deafening “boom!” “Every day was a new adventure in pain and the unknown,” he said.

A few years later, the Wrights had a son, but life did not return to normal. While the bombing didn’t cause his eventual divorce, it didn’t help either. Something nameless stalked him, a ghost figure who might strike again.

FORGIVENESS: On a sum

mer day six years after the attack, Gary heard a voice say, “Look, you’re Christian. You believe in God, right? Well, if Christ can be crucified, be put on a cross by these people, and he forgave them—then you don’t have a choice.”

He pulled his car over and wept. “I just let it go. I let the whole thing go.”

SIX-YEAR HIATUS

After being spotted, Ted sent no bombs until 1993. In that time, he repeatedly reached out for psychological help without success.

In 1991, he was taken with his cardiologist. He hoped to impress her by going back to college for journalism. Sensing a romance was unlikely, he later abandoned the plan.

BROTHERS TORN APART

When Dave and longtime girlfriend Linda started living together in New York state in 1989, Ted wrote Dave, saying he was a fool to throw away his freedom and life in the desert for a woman:

“So as long as you’re selling out, you may as well ... become a lawyer.”

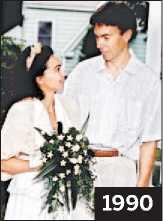

Ted never met Linda and didn’t attend her and Dave’s wedding in 1990-the same year their father committed suicide after battling lung cancer. Ted called home to comfort their mother, but did not attend the funeral.

In 1996, Dave worked closely with the FBI to catch the Unabomber- his brother-before he could strike again.

“I can’t express how painful it felt to point out the exact location of Ted’s cabin [to the FBI] among the blue whorls on the map, knowing that I might be sending my mentally ill brother to his death.”

5. Could it be Ted?

Dave studied the manifesto, and his stomach sank. The words “cool-headed logicians” stopped him. Ted used that phrase.

Rummaging around to find family letters, Dave compared them with the language in the manifesto. “Maybe there’s a 50 percent chance that he’s this person,” he concluded.

Dave’s wife, Linda, had been the first to make a connection. Vacationing in Paris, she spotted a series of newspaper stories on the Unabomber that presented the serial killer as an anti-technology zealot.

Linda couldn’t help but see parallels to her brother-in-law.

Over the many years that Linda knew the Kaczynskis—she and Dave had been lab partners at Evergreen Park Community High School—she often listened to them recount stories of Ted’s odd behavior.

Linda knew his writing voice intimately from the years the family spent reading his letters. She expressed concern that Ted was mentally ill.

After The Washington Post published the manifesto in September 1995, Linda downloaded a copy from the Internet and read it. “It just seemed as though it was the voice of Dave’s brother,” she said recently.

Dave didn’t know what to believe. How could this figure he once idolized, who looked after and encouraged him, how could Ted become a killer? Had Dave been blinded by family love? Could he have grown up in the presence of evil and not known it?

Soon after, in January 1996, Dave contacted the FBI through an attorney.

For weeks he showed agents letters Ted had written to their family, and Dave traveled to help interview people Ted knew. He held out hope his brother was innocent, but that hope evaporated when Dave got a call from his FBI liaison. The agent said she was sorry: Ted had moved to the top of the suspect list.

Less than a week later, Ted was arrested.

Map Graphic Text

1972

Where Ted Kaczynski lived or went to school

Fatal bomb

Non-fatal bomb

WASH.

Bomb #16

April 24, 1995

Ted's thoughts on killing forestry executive Gilbert Murray:

“No regret about the fact that... bomb blew up the ‘wrong' man.”

MONT.

Bomb #11

Dec. 11, 1985

On killing computer store owner Hugh Scrutton, who died 30 minutes after the blast:

“‘blown to bits’....

Excellent. Humane way to eliminate somebody.

He probably never felt a thing. 25000 dollar reward offered.

Rather flattering.”

CALIF.

UTAH

Bomb #1 May 26, 1978

On his first bombing, which injured a Northwestern University policeman:

“I hoped that a student... would open the package... and blow his hands off, orget killed. I checked the newspapers carefullyafter- ward.... I am proud of what I did.”

Bomb #3: Nov. 15, 1979

On trying to blow up a plane headed from Chicago to Washington, D.C.:

"Unfortunately plane not destroyed, bomb too weak.... I will try again if I canget a better explosive. At least it gave them agood scare."

MICH.

MASS.

Bomb #15

Dec. 10, 1994

ILL.

VA.

TENN.

On the bomb that killed advertising executive Thomas Mosser:

“The device in experiment 244 was used in December 1994 and it gave a totally satisfactory result.”