Various Authors

Special Issue on The Dawn of Everything

Egalitarianism made us the symbolic species

Woodburn’s concept of ‘egalitarianism’

Evolutionary models of egalitarianism

Evidence in our bodies and minds for ancestral egalitarianism

What is a history of humanity?

Graeber and Wengrow’s mixed bag of humanity’s traits

African hunter-gatherers, immediate-return economies and ‘original affluence’

The sapient paradox by any other name?

Social anthropology and the ‘ideology of blood’ tradition

What African hunter-gatherers do with, and say about, ritual use of red substances

Introduction: why I bought four copies of The Dawn of Everything

Hunter-gatherer pasts: between equality and complexity

From hunting to hierarchy: ‘complexity’ in hunter-gatherer research

Entrenched inequality? Hunter-gatherers and fortification construction

Fortified hunter-gatherer settlements in West Siberia

The Gini coefficient: measuring ‘silly things’?

Measuring inequality in West Siberia

Inequality, equality and the architects of change

Fortifying narratives: social and evolutionary sciences as eternal counterparts?

Seasonality and schismogenesis

Introduction: the moment is now

Schismogenesis: doing (and undoing) difference

Conclusion: we are all tinkers

Periodicity: seasonal or monthly?

World mythology: how we got stuck

Amerindian stories about getting stuck

The Hunter Monmanéki and his Wives: Amazonia, Tucuna

‘Cancelling’ hunter-gatherers for the cause of twenty-first-century urbanism

Complex hunter-gatherers as a root of elite-driven economic intensification

The prehistoric-to-contemporary left/right divide: summarising DoE’s political agenda

The subsistence-based alternative

How would making this knowledge more publicly present impact our current debates?

Introduction{1}

Camilla Power & Chris Knight

Camilla Power, Dept of Anthropology, University College London, 14 Taviton St, London, WC1H 0BW camilla.power@gmail.com

Chris Knight, Dept of Anthropology, University College London, 14 Taviton St, London, WC1H 0BW chris.knight@live.com

These papers were collected from a session of the Conference of Hunting and Gathering Societies (CHAGS13) in Dublin, 27 June–1 July 2022, focused on The Dawn of Everything (Graeber & Wengrow 2021). It was held not many months following its publication and less than two years after the tragic loss of David Graeber. By now we may be seeing a little more clearly where this book with its enticing vista of explorations in deeptime human history will settle.

David Graeber and David Wengrow’s ‘fun’ project has had phenomenal success, topping nonfiction bestseller lists and being translated into over 30 languages. Fertile, creative, imaginative, the book is written in line with Graeber’s usual principle – in a style engaging for his mum. Rambling and sprawling for almost 700 pages, there’s something for everyone. Every reader, it seems, finds in it just what they seek, and each has their own opinion.

For anthropology and archaeology – disciplines usually represented by arcane texts impenetrable to outsiders – it’s really refreshing. The big, old questions about what it means to be human, the wealth of possibilities, the stories we tell about how we got here are dusted off and put right back on the table again. This is big news because social anthropology has been ducking all discussion of human origins for the best part of a century now. To see these topics firmly ensconced in a social science framework is electric. That alone means this book, with all its fanfare, matters. It has carved out a space.

Yet, despite the title (referencing the anti-semitic historian of religion Mircea Eliade), the authors still evade origins except as a mythological concept: ‘a vast canvas for the working out of our collective fantasies’ (2021: 78). As Ian Watts (2024:235) argues, for Graeber and Wengrow, a ‘single human “us” can only be inferred from ~30 ka’. The actual stretch of time when we became all-singing, all-dancing, language-speaking symbolic culture-bearing humans is abandoned as unknowable.

The contributions here are thoroughly interdisciplinary from social anthropology, evolutionary anthropology and archaeology as well as anarchist perspectives. Overall, responses range from highly positive to critical. Importantly, whether it is in praise or quite harsh critique (we’d better admit, one of us has written a review titled: ‘Wrong about (almost) everything’!) each article has a distinct focus. This reflects the sheer range of material – cultures, time periods, continents – covered by this hugely ambitious book.

The Dawn of Everything begins with its ‘indigenous critique’, responsible for goading and stimulating the development of European political philosophy. Drawing on his long-term fieldwork with Hai//om people of northern Namibia, Thomas Widlok envisages an ‘indigenous critique’ of two key themes: oscillatory switches framed by seasonality, and ‘schismogenesis’, termed here ‘doing seasons’ and ‘doing difference’. The three named seasons of the Hai//om cycle interweave continuities with discontinuties. In conversation, Hai//om people use expressive repetition to emphasise continuity and values of stability. They don’t hanker for change or feel stability to be burdensome, which, Widlok hints, could be associated to ‘progressive narratives’ found in European and farming traditions. Doing seasons without ‘unruly switching’, their indigenous voice critiques the structuralist/dualist perspective of seasons underlying The Dawn of Everything ‘coloured by agricultural folks in the high latitude zones’ (Widlok 2024:312). Life histories collected from Hai//om seniors also provide the opposite of ‘doing difference’ – that is, ‘undoing difference’, when they describe living with !Xû neighbours as ‘children of one woman’ (2024:313).

Chris Knight uses another source of indigenous voice – Amerindian mythology – to interrogate Graeber and Wengrow’s oscillatory model, addressing their key question about ‘how did we get stuck?’ A structuralist binary lies at the heart of these mythic discourses, beating to a lunar cyclical rhythm. Although Graeber and Wengrow pay little attention to indigenous myths, Knight discerns ‘an uncanny fit’ between their ‘getting stuck’ thesis and a motif central to myths from all over the world: a preoccupation with loss of periodicity and movement between worlds. This is taken to a high degree of elaboration in the Tucuna story ‘The hunter Monmanéki and his wives’ which opens The Origin of Table Manners, the third volume of Lévi-Strauss’s Mythologiques. The animal wives move through an algebraic sequence of structural oppositions, more and more handicapped by the increasingly absurd demands of patrilocal marriage. The last wife literally flies apart, split into upper and lower halves. Knight views this story as an Amazonian voice explaining how we ‘got stuck’.

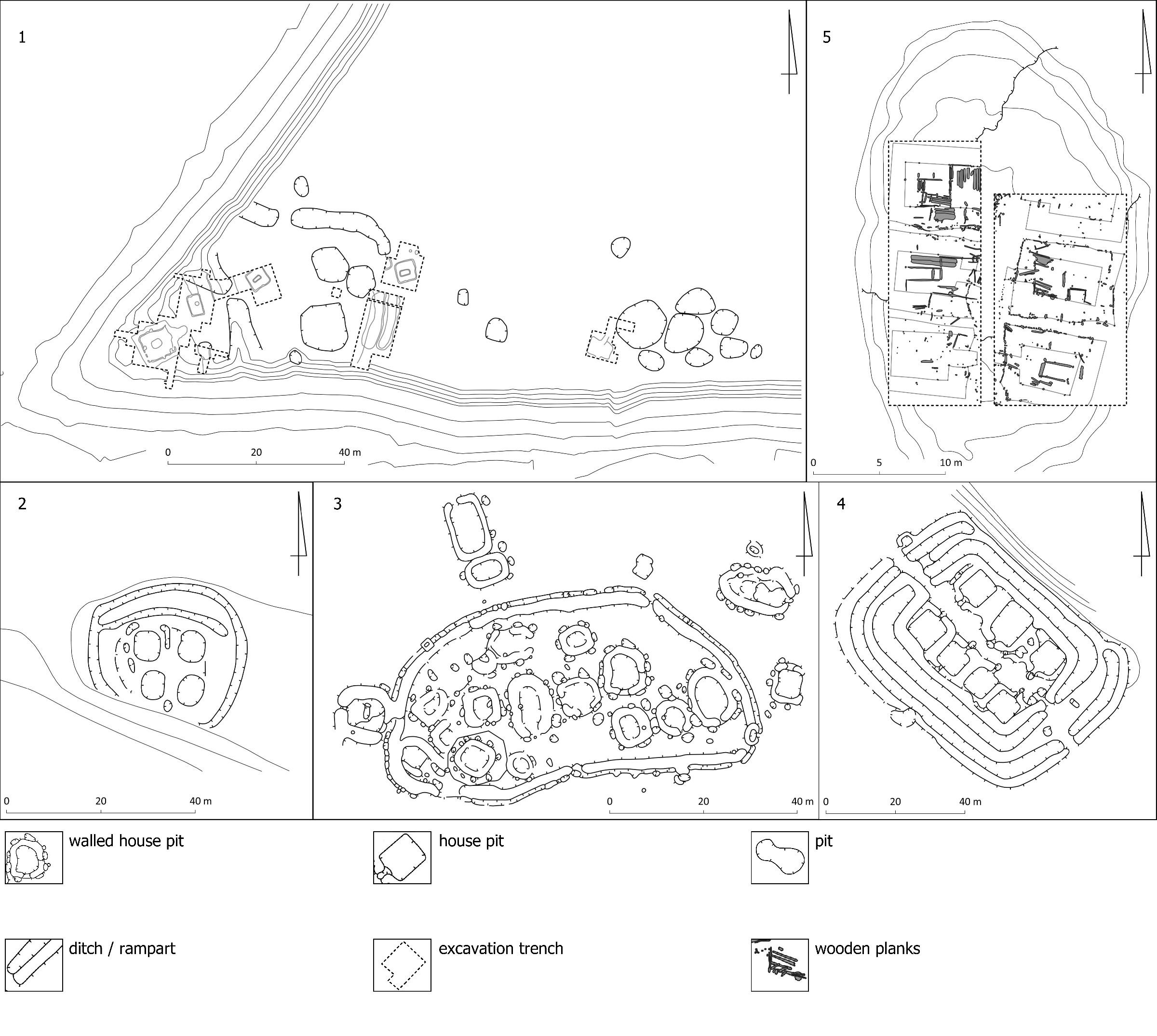

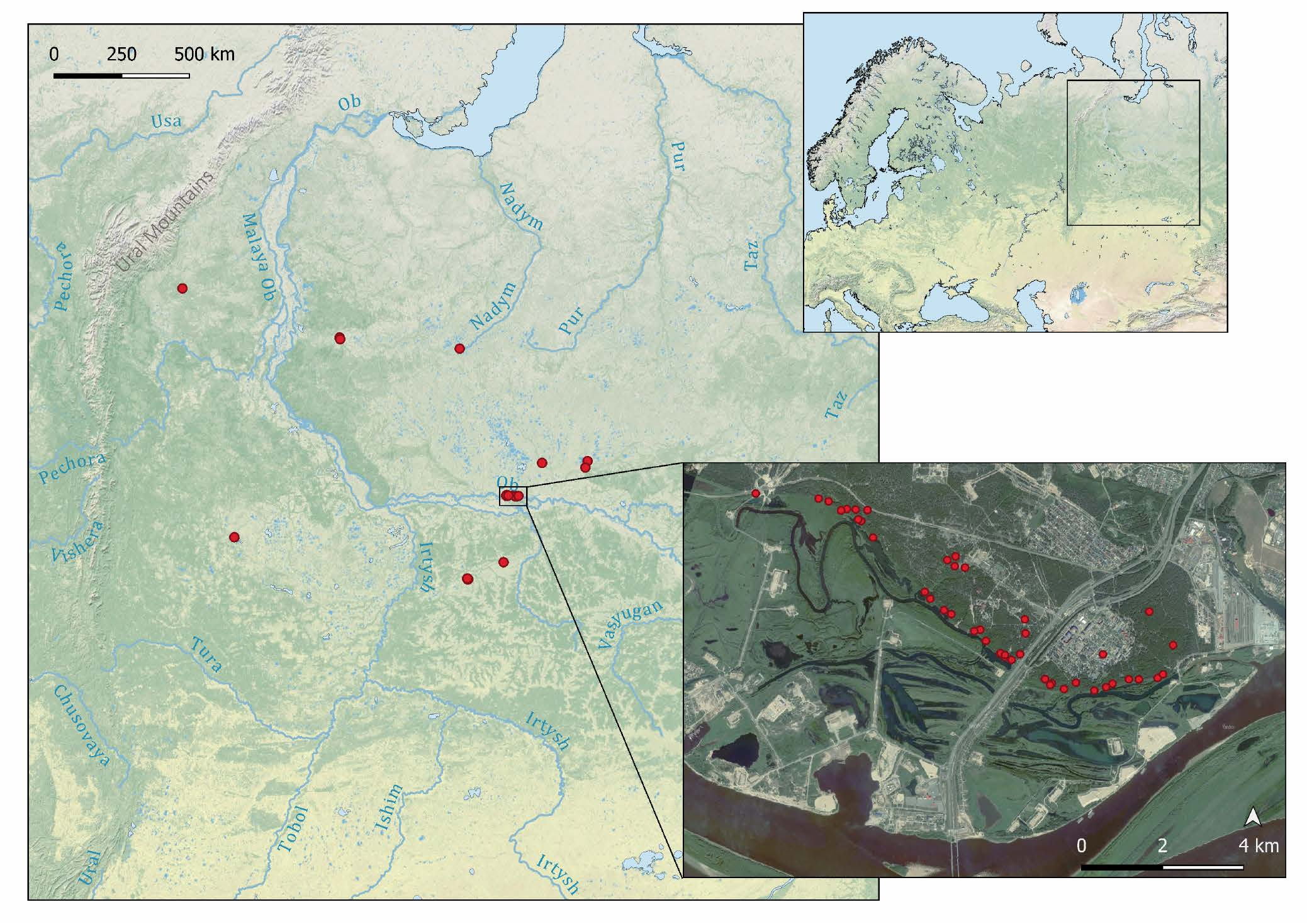

Archaeologist Tanja Schreiber describes her personal experience of Graeber and Wengrow’s book as empowering and emancipatory for her research. Their refusal to accept narratives of ‘linear progression from simplicity to complexity’ at once sweeps away the old evolutionist, stageist models that still haunt archaeology (Schreiber 2024:266). With a fascinating case study of Western Siberian foragers who built fortified settlements over eight millenia, she is able to show long-term oscillatory changes between greater and lesser social inequality. Pushback and contestation over growing inequality may be seen in conscious manipulation of space within the settlements. As ‘“architects” of their own social arrangements’ (2024:265), people of these Siberian communities fostered denser cohabitation, perhaps strengthening communal solidarity to resist inequalities.

Other contributors have queried the attitudes of Graeber and Wengrow to understanding egalitarian systems, which they tend to belittle and downplay, as well as their rather old-fashioned concepts of evolutionary theory. More recently, this has been expressed with extraordinary vehemence by David Wengrow (2023) as ‘This idea must die: We used to be equal.’ Unsurprisingly, hunter-gatherer fieldworkers with genuine (not romantic) experience of the sophisticated politics of egalitarian groups are left bewildered.

From an evolutionary perspective, Camilla Power roundly opposes the idea that just anything goes in our evolution as Homo sapiens. While Graeber and Wengrow say on their first page, regarding the period of our speciation, that ‘we have next to no idea what was happening’ (2021:1), we can be fairly confident about what wasn’t happening. Our anatomy, psychology and cognition provide evidence for constraints. The evolution of our cooperative eyes, intersubjectivity, large brains, a ratchet effect of cultural accumulation and language itself required stable, protracted periods in sociopolitical contexts of significant egalitarianism. Power understands gender relations to be pivotal in the processes of increasing levels of social tolerance and aversion to inequity.

James Van Lanen also critiques what he sees as a gendered structure arising in The Dawn of Everything with counterposition of brutish, masculinist, prestige-hungry hunters opposed to more communal, matriarchal early women farmers, busy creating an ‘ecology of freedom’. A whole array of lifeways of non-intensifying, egalitarian peoples, says Van Lanen, have been ‘cancelled’ from this ‘new history of humanity’ (Van Lanen 2024:361). Yet it is precisely these indigenous peoples who bear the most sustainable cultural knowledge, and are most vulnerable to ethnocide from agricultural expansion. Paradoxically, he claims, Graeber and Wengrow end up advocating statist, urban bureaucracies in creating a fallacious prehistoric ‘left/right’ divide.

In our coda, Doerte Weig offers a prose poem, or creative intervention, inspired in part by Graeber and Wengrow’s invitation to freedom of form and experiment, in part also by the primarily sociosomatic experience of egalitarian living. As a fieldworker who has lived among Central African Forest groups, she writes poignantly about what it could mean to gift that knowledge to so many people, to educate whole generations of schoolchildren in what it means to be human.

As Ian Watts writes, The Dawn of Everything was clearly intended to be collectively empowering. It has been felt to be by very many readers including our contributors. Knowing that our current parlous state – being stuck in subordination to a blind and greedy minority – is not natural or normal in human history should empower us to organise ourselves differently, to become architects of resistance. But if we bin scientific understanding of our origins – the egalitarian origins of all our shared imaginaries – how can we know our true potential, our own distinctively human resources and capacities, forged over hundreds of thousands of years? Can talking about The Dawn, the real ‘dawn of everything’ only ever be a myth?

References

Graeber, D & Wengrow, D 2021. The dawn of everything. London: Allen Lane.

Knight, C 2021. Wrong about (almost) everything. focaal blog, Dec 2021. https://www. focaalblog.com/2021/12/22/chris-knight-wrong-about-almost-everything.

Schreiber, T 2024. Architects of change: inequality and resistance among Siberian foragers. Hunter Gatherer Research 8(3–4) (2024 [for 2022]):265–303.

Van Lanen, JM 2024. ‘Cancelling’ hunter-gatherers for the cause of twenty-firstcentury urbanism: The dawn of everything’s left/right divide in prehistory. Hunter Gatherer Research 8(3–4) (2024 [for 2022]):347–367.

Watts, I 2024. Before The dawn of everything. Hunter Gatherer Research 8(3–4) (2024 [for 2022]):233–264.

Wengrow, D 2023. This idea must die: we used to be equal. Portico Magazine. Spring. https://magazine.ucl.ac.uk/this-idea-must-die-david-wengrow/.

Widlok, T 2024. Seasonality and schismogenesis: doing seasons and doing difference after ‘dawn’. Hunter Gatherer Research 8(3–4) (2024 [for 2022]):305–319.

Egalitarianism made us the symbolic species{2}

Camilla Power

Dept of Anthropology, University College London, 14 Taviton St, London,

WC1H 0BW camilla.power@gmail.com

Abstract: ‘The world of hunter-gatherers […] was one of bold social experiments’ say Graeber and Wengrow, ‘a carnival parade of political forms’. But did the boldest social experiments of our ancestors – language and symbolic culture – constrain these possibilities? Aspects of our anatomy, psychology and cognition that were necessary preadaptations to language – cooperative eyes, intersubjectivity, large brains, a ratchet effect of cultural accumulation – required stable sociopolitical contexts of significant egalitarianism to evolve among our middle Pleistocene ancestors. This implies political strategies for minimising and periodically nullifying dominance relations, through dynamics of day-to-day individualistic counter-dominance with occasional displays of collective reverse dominance. Because of the very high costs for mothers who had to provide high-quality nutrition and reliable allocare for large-brained babies, the most telling aspect of this would be gender resistance, establishing gender egalitarianism. middle Pleistocene populations with more hierarchical tendencies were least likely to have become language-speaking, larger-brained ancestors of Homo sapiens.

Keywords: egalitarianism, human evolution, language, brain size, deep social mind, gender, Dawn of Everything

Introduction

In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow challenge the assumption that our distant ancestors before agriculture were hunter-gatherers living in tiny, egalitarian bands. That idea, they claim, consigns those ancestors to ‘a prolonged state of childlike innocence’ (2021:2). In their attempt to ‘tell another, more hopeful and more interesting story’ (2021:3), they envisage early hunter-gatherers as political creatives, imaginatively exploring various social systems, building up authority structures and tearing them down just for amusement. They depict ‘the world of hunter-gatherers […] before the coming of agriculture’ as ‘one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms’ (2021:4).

In rejecting parochial horizons, Graeber and Wengrow could be on the right track. Recent archaeological evidence of early H. sapiens populations in Africa (Dapschauskas et al 2022; Miller & Wang 2022) is more indicative of connected and networked bands. These studies suggest reticulation and linkage of populations on Pan-African scales, with striking broad similarity of culture, rather than isolated, small-scale, parochial boundaries. Graeber and Wengrow (2021:121–125) connect the nomadic privilege of voting with one’s feet to escape attempted domination with these wider horizons.

But the premise that creating and maintaining an egalitarian social order is ‘simple’ or ‘childlike’ is problematic. Graeber and Wengrow never fully consider the complex reality of maintaining an egalitarian political balance. In Morna Finnegan’s words: ‘complex egalitarianism cultivates individuality and autonomy through the communal labour of distribution of social power’ (Power et al 2017:27). Finnegan (2008; 2013) prefigured Graeber and Wengrow’s notion of oscillation of power between groups, in her case with gender dynamics at the core. She says: ‘egalitarian societies do play routinely with a kind of shadow hierarchy, where intersexual conflict and the threat of collapse serve as a powerful motor for the movement of power across the social landscape’ (Power et al 2017:27). Not only food is demand-shared, but power itself. Polly Wiessner cites a Ju/’hoan conversation defining the core of their culture: ‘“It is not trance dance, hunting techniques, apparel or songs that are the essential elements of our culture but rather relations of respect and appreciation for what others have to offer. We walk/talk softly, unlike the Bantu who are big penises” (an expression for relations of dominance)’ (2022:3).

In human history there have been no social experiments bolder or more original than language and symbolic culture. In this article, I ask: what if these boldest of all social experiments by our ancestors – our African ancestors of H. sapiens – in fact constrained the political possibilities? What if only certain kinds of political arrangements could have enabled language and symbolism to emerge? Where would that leave Graeber and Wengrow on the ‘infantilising’ effects of imagining egalitarian ancestry?

This paper begins by discussing James Woodburn’s usage of the term ‘egalitarian’ and his view on egalitarianism in social evolution. It continues with the major evolutionary models advanced for egalitarianism, and how it has been linked to increasing cognitive sophistication rather than ‘infantile simplicity’ (Erdal & Whiten 1996; Boehm 2001; Migliano & Vinicius 2021). I then outline universal features of Homo sapiens that are unlikely to have evolved without prolonged periods of relative egalitarianism among human ancestors. I consider evidence that gender relations were critical in this process, and probable timelines of such protracted tendency to egalitarianism as we evolved.

Woodburn’s concept of ‘egalitarianism’

Writing of her experiences with the Ju/’hoansi, Megan Biesele says:

Egalitarianism, though it may seem casual or lackadaisical to outsiders, or even a saccharine, romantic concept, is underpinned by determined effort and by fierce and sustained attention to expectations and rules. I wondered whether, judging by its long-term success, this effective social technology had taken a lot of trial and error to perfect during prehistory. I came to think of egalitarianism as another of the great cultural achievements of humankind. (2023:154)

Graeber and Wengrow dislike the term ‘egalitarianism’ (see eg 2021:76, 86–87, 125–126), which has been used – and regularly interrogated – by huntergatherer researchers over a lengthy period (Fried 1967; Lee 1982; Woodburn 1982; Solway 2006; Schultziner et al 2010; Finnegan 2013; Dyble et al 2015; Bird-David 2020; Reckin et al 2020; Stibbard-Hawkes 2020; Singh and Glowacki 2022). They repeat the mantra ‘it remains entirely unclear what “egalitarian” even means’ (2021:75, 125), try out a negative definition of ‘absence of hierarchy’ (75, 125), then plump for ‘living in some collective group-think’ (95), that is, adhering to an ideal that ‘people feel they ought to be the same’ (126). Wiessner (2022:3) gives this short shrift, since nomadic bands rely on people having diverse skills, characters and abilities: ‘egalitarian relations are not about sameness in small-scale societies, but rather about respect and appreciation of different skills offered by group members to build complementarity and dependency’. Striking the balance between autonomy and interdependency is what gives egalitarianism its complex, fluid dynamic.

In his classic article on the mechanisms used to maintain that balance – ‘Egalitarian Societies’ (1982) – James Woodburn was crystal clear:

I have chosen to use the term ‘egalitarian’ to describe these societies of near-equals because the term directly suggests that the ‘equality’ that’s present is not neutral, the mere absence of inequality of hierarchy, but is asserted. (1982:431)

This attitude of ‘politically assertive egalitarianism’ relies on deeds not words, or, we might say, direct action: ‘The verbal rhetoric of equality may or may not be elaborated but actions speak loudly: equality is repeatedly acted out, publicly demonstrated, in opposition to inequality’ (1982:432).

While Woodburn conceded many societies were in some sense egalitarian, he argued only ‘immediate-return’ hunter-gatherers were able to give this political attitude its full expression. Such societies had no storage; were vigilant in egalitarian ideology and practice; minimised specific personal dependency (but not interdependency); and ensured freedom of choice in residence and association, direct access to necessities of life, and entitlement to share for all members. His category of immediate-return may be problematic. Wiessner has argued that ‘storage’ of far-flung social relations called on during lean seasons implies delayed-return (1982; 2002). And Woodburn himself recognised that the institution of bride service – a hunter’s obligations to his wife’s kin, his in-laws – introduced ‘a delayed-return element’ (1980:111). Relative to nonhuman primate hunting which really does involve consumption on the spot, any separation of a hunter from his kill can be described as delayed-return.

But the key point here is the prevalence of egalitarian immediate and more hierarchical delayed-return types of hunting societies reaching back into the past. Woodburn thought both types were likely to be ancient, prior to farming; considering Africa, in a world of hunter-gatherers, a higher proportion may have had delayed-return systems (1980:112; 1998:61; 2005:20). Immediatereturn systems ‘though not simple in form, are intrinsically simpler than delayed-return systems and it seems plausible to argue that there will have been a time at which all societies had immediate-return systems’ (2005:20). Remarkably stable and resistant to change through time, early forms of huntergatherer organisation were immediate-return and egalitarian. He made the ‘very sweeping claim. Such immediate-return systems constitute a stable and enduring social form, internally coherent and meaningful […] not just capable of self-replication but tending always to self-replication’ (2005:21).

Evolutionary models of egalitarianism

In his tentative reconstruction of hunter-gatherer societies of the past (1980), Woodburn definitely avoided any idea of what Graeber and Wengrow call ‘our modern notion of social evolution’ (2021:5). By this, they in fact mean the ‘stage’ models advanced by nineteenth-century evolutionists such as Lewis Henry Morgan (followed by Engels) with hunter-gatherers placed in ‘savagery’, farmers in ‘barbarism’ and urban state dwellers in ‘civilisation’. Even the ‘neo-evolutionists’ they refer to – Leslie White, Julian Steward, Morton Fried, Elman Service, early Marshall Sahlins – were working back in the 1950s–1960s prior to the development of modern evolutionary anthropology and ecology. As evolutionary anthropologist Vivek Venkataraman explains (2022): ‘Scholars do not take stage models seriously today. There is little intellectual connection between stage models and modern evolutionary approaches toward studying hunter-gatherers.’ This involves a whole generation and more of hunter-gatherer research since Man the Hunter that Graeber and Wengrow’s book barely addresses.

While the Dawn of Everything authors identify ‘egalitarian’ with assumptions of ‘simple’ or ‘primitive’, in fact behavioural ecologists and evolutionary anthropologists have investigated the sophistication of cooperative, strategic and cognitive flexibility involved in egalitarian and supposed ‘small-scale’ societies (eg Dyble et al 2015; Dyble 2020; Boyd & Richerson 2022; Glowacki & Lew-Levy 2022; Kraft et al 2023). Migliano and Vinicius (2021) view egalitarian social relations as a vital component of the ‘foraging niche’ engendering multilevel social structures and cumulative cultural evolution.

Egalitarianism appears hard to explain using Darwinian theory premised on individual competition. One of the originators of Machiavellian intelligence theory, Andrew Whiten (Byrne & Whiten 1988), and his student David Erdal saw that Machiavellian intelligence could generate the difference between primate-style dominance hierarchies and typical hunter-gatherer egalitarianism. Machiavellian intelligence is a subtle idea that sees animals in complex social groups competing in evolutionary terms by becoming more adept at cooperation, and more capable of negotiating alliances. In this theoretical perspective then, the significant increases of brain size in the primate order, from monkeys to apes, and then from apes to hominins and genus Homo, result from increasing political complexity and ability to exploit alliances.

Erdal and Whiten offered an evolutionary and dialectical explanation for human egalitarianism, which they termed ‘counter-dominance’ (Erdal & Whiten 1994; 1996; Whiten & Erdal 2012). At a certain point, the ability to operate within alliances exceeds the ability of any single individual, no matter how strong, to dominate others. If the dominant tries, he (assuming ‘he’ for the moment) will meet an alliance in resistance who together can deal with him. Once that point is reached, the sensible strategy becomes not to try to dominate others, but to use alliances to resist being dominated oneself. They saw counter-dominance as fundamental to the evolution of human psychology, with competing tendencies for individuals to try to get away with bigger shares where opportunity presents, but, faced with demands from others, to give in and settle for equal shares.

This model predicts much of what we find: egalitarian hunter-gatherers are vigilant in case anyone gets above themselves using techniques of demand-sharing, with an attitude of ‘don’t mess with me’ and humour as a levelling device, rejecting any possibility of coercion since no particular individual is in charge. Erdal and Whiten (1996:143) embed their account in close reading of ethnography for counter-dominant behaviours (vigilantsharing, counteracting attempts at dominance). Whiten (1999) subsequently proposed ‘deep social mind’ emerging through a prolonged phase of egalitarianism coevolving with mutual mind-reading and cultural transmission, making up the human hunter-gatherer sociocognitive niche. Counter-dominant tactics and dispositions underpinned cooperative mind-reading – necessarily, no one wants their mind read by somebody dominant – and enabled cultural sharing and accumulation.

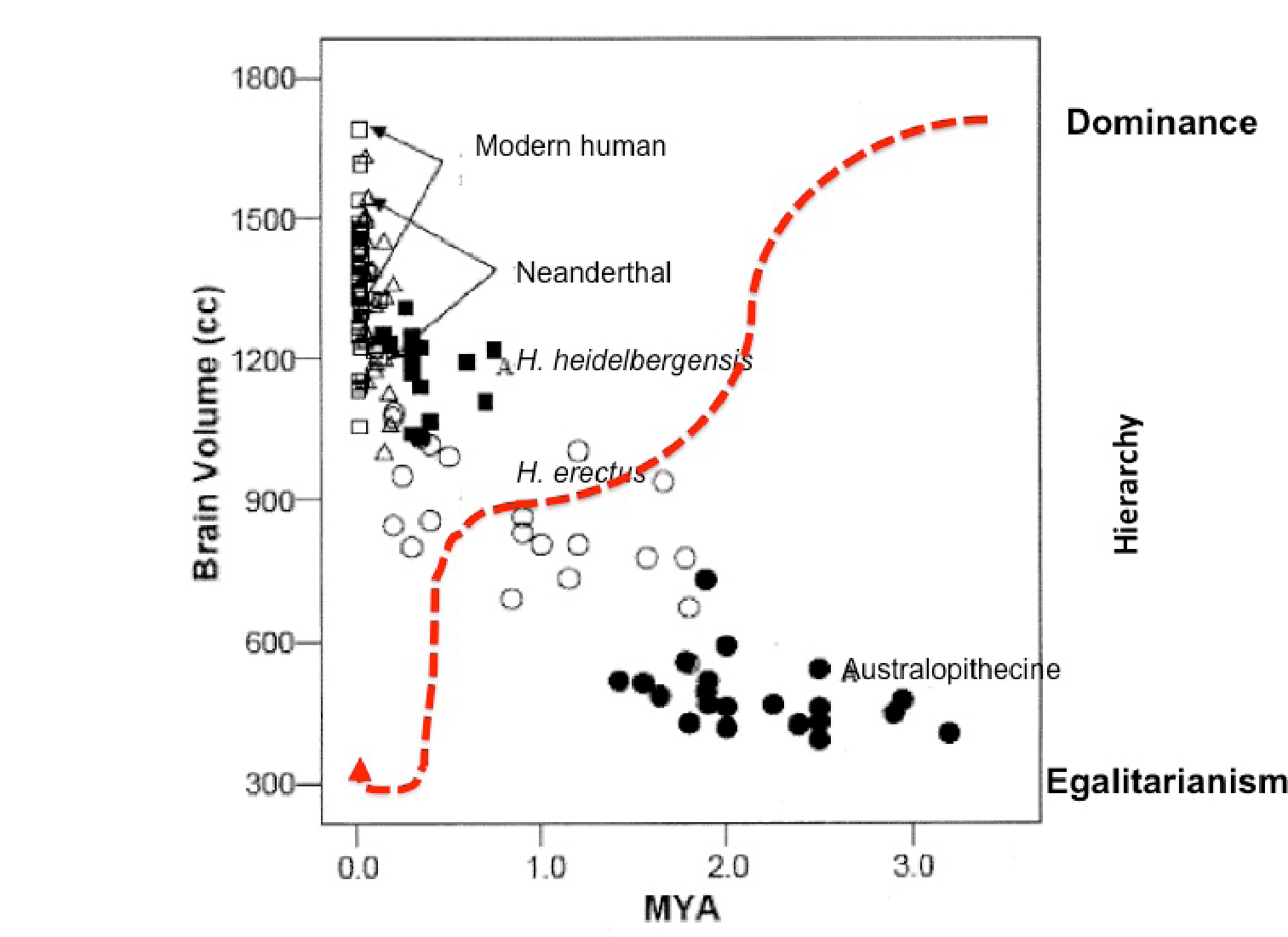

Erdal and Whiten illustrate this trajectory with their ‘U-shape curve’ (Erdal & Whiten 1996:141, Figure 12.1; Whiten 1999:180, Figure 10.1) originally derived from Bruce Knauft (1991). This shows pronounced reduction in hierarchy through evolutionary time bottoming out in a period of uncertain duration as hunter-gatherer ancestors maximise egalitarianism; this precedes a steep rise in inequality during the past 10–15,000 years. Of course this ‘story’ that farming, herding and settlement produced that jump in inequality is anathema for Graeber and Wengrow. In their book, hunter-gatherer specialists are ‘romantic’ if they suggest that our evolved psychologies, emotions and cognition were shaped by selection pressures that prevailed when our ancestors led an egalitarian way of life. As fairly hard-bitten evolutionary psychologists of the St Andrews school, Erdal and Whiten are not obviously ‘romantic’. From their starting point in nonhuman primate politics, the key question is not ‘how did we get to be unequal?’ but rather ‘how did we first become equal’?

With Knauft and Chistopher Boehm in the 1990s, Erdal and Whiten engaged in key debates on egalitarianism, violence and resistance to dominance among hunter-gatherer ancestors. Graeber and Wengrow make evolutionary (and cultural) anthropologist Boehm their chief target, ignoring Erdal and Whiten’s important contribution. Boehm’s model (2001) argues for a group or collective intention rather than individualistic negotiations. Because humans descend from great apes, says Boehm, our distant ancestors must have been psychologically adapted to great ape politics of dominance, violence and resistance. But in our lineage, collective resistance culminated in everyone ganging up to prevent any would-be leader from dominating the group. Chimpanzee-style dominance was overturned by solidarity action from below, resulting in ‘reverse dominance’ – rule by a morally aware community, consciously determined to maintain equality.

Graeber and Wengrow are very positive about Boehm’s idea that, by nature, humans resist dominance. As they put it, humans ‘do appear to have begun [history] with a self-conscious aversion to being told what to do’ (2021:133). They acknowledge his finding that extant hunter-gatherers display ‘a whole panoply of tactics collectively employed to bring would-be braggarts and bullies down to earth – ridicule, shame, shunning […] none of which have any parallel among other primates’ (2021:86). Note, this is one of the only places in the book where they apprehend a radical shift between nonhuman primate and human politics. They recognise Boehm’s recognition of hunter-gatherer ‘actuarial intelligence’: ‘while the bullying behaviour might well be instinctual, counterbullying is not: it’s a well-thought-out strategy’ (2021:86). But they are mighty disappointed when Boehm still insists humans were basically egalitarian until around 12,000 years ago, ‘casually tossing early humans back into the Garden of Eden once again’ (2021:87).

While Graeber and Wengrow claim that Boehm ‘assumes that all human beings until very recently chose instead to follow exactly the same arrangements’ (2012:87), in fact Boehm correlates the process of increasingly egalitarian, reverse dominant behaviours with our speciation as Homo sapiens (2001:194– 196). Variation in sociopolitical traits and behaviour, between individuals and between populations, must have existed. Boehm argued from this background for selection of a successful ‘group’ strategy of a politically conscious, egalitarian order that would spread across groups as it became attractive to nondominant but nonsubmissive individuals, altering despotic group dynamics. Group selection prevailed when within-group competition was significantly reduced (2001:210–212).

Both models – Erdal and Whiten’s ‘counter-dominance’ and Boehm’s ‘reverse dominance’ – capture aspects of existing hunter-gatherer politics. While Erdal and Whiten provide evolutionary continuity of ‘Machiavellian’ individualistic and autonomous strategies, Boehm’s reverse dominance engages with ‘revolutionary’ moral and collectively determined ones. Crucially, both models also leave aside the important question of gender.

Evidence in our bodies and minds for ancestral egalitarianism

Certain universal features of H. sapiens, deriving from our Middle Pleistocene emergence, imply or underpin sociopolitical contexts of significant egalitarianism:

-

‘cooperative’ eyes

-

very large brains

-

the evolutionary origins of language.

Let’s look at each of these indicators in turn.

Cooperative eyes

Our cooperative eyes could possibly be a primitive feature of genus Homo. Alone of over 200 primate species, we have evolved eyes with an elongated shape and a bright white sclera background to a dark iris (Kobayashi & Kohshima 2001). Known as ‘cooperative eyes’ (Tomasello et al 2007; Hare 2017), they invite anyone we interact with to see easily what we are looking at. By contrast, great apes have relatively round, dark eyes, making it more difficult to judge their gaze direction.

One study (Caspar et al 2021) found no evidence for a link of social cognition and eye pigmentation in nonhuman primates, but Kano et al (2022) used experimental methods to show both humans and chimps could discriminate eye-gaze direction better in humans than chimps. Mearing and colleagues (2022) demonstrated association of both prosociality and social tolerance measures with light sclerae across primates, while dark sclerae associated to reduced cooperation and increased lethal violence measures.

While there is variability in sclera melanin among great apes (Mayhew & Gómez 2015), Homo sapiens has evolved to fixation in the lack of this characteristic. Our eyes appear adapted for mutual mind-reading, also known as intersubjectivity; our closest primate relatives more or less block this off. To look into each other’s eyes, asking ‘can you see what I see?’ and ‘are you thinking what I am thinking?’ is completely natural to us from an early age (Tomasello & Rakoczy 2003). Infants, children and adults all show preference for faces, toys and cartoon characters with white sclerae (Hare 2017:168–169).

‘Humans’, notes Grossmann (2017:3), ‘compared with other great apes, possess a unique sensitivity to information from the eyes’. This capacity of looking into the eyes for information about an individual’s emotional and mental state underpins our unique forms of learning, cooperation and communication, with mutual gaze crucial to forming shared intentions (Tomasello et al 2005; Grossmann 2017; Hare 2017).

The most convincing account of how, when and why intersubjectivity and cooperative eyes coevolved is given by Sarah Hrdy in her landmark book Mothers and others (2009). We do babysitting in all human societies, mothers being happy to hand over their offspring for others to look after temporarily. African hunter-gatherers deploy this collective form of childcare (Hewlett and Lamb 2005; Jang et al 2022; Chaudary et al 2023), indicating that it was routine in our heritage. In stark contrast, hyperpossessive great ape mothers – chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans – rarely let their babies go.

As babies needed to attract and hold the attention of various carers, they developed acute sensitivity to the moods, emotions and intentions of those carers, needing to read their faces, expressions and gaze direction. At the same time, they became increasingly expressive of their own feelings and emotions to engage carers. This clears the pathway of mutuality in mind-reading – where a purely Machiavellian stance would only go one way. It fosters meshing of emotional states, grasping how you look to the other, and ultimately sharing of intentions based in mechanisms like reading eye-gaze.

Hrdy’s babysitting model gives us distinctly gendered initial conditions for Whiten’s ‘deep social mind’. Core female kin coalitions involved in such cooperative childcare create bubbles or pockets of increasing social tolerance, egalitarian sharing and intersubjective understanding – exactly the conditions promoting cultural intelligence and transmission, curiosity and exploration (van Schaik & Burkart 2011; van Schaik et al 2019; Migliano & Vinicius 2021; Forss & Willems 2022; Boeckx 2023).

Large brains

Our very large brains, still enlarging as H. sapiens speciated (Will et al 2021), increased the need of mothers and children for more energy, with seasonal sustainability of nutrition (Van Schaik et al 2012). Adult humans today have upwards of three times the brain volume of a chimpanzee (Isler & Van Schaik 2012). Brain tissue is extremely expensive in terms of energy requirements (Foley & Lee 1991; Aiello & Wheeler 1995; Aiello & Key 2002; Kuzawa et al 2014) besides nutrients like fatty acids crucial to brain development. Doing the whole job by themselves, great ape mothers are constrained in the amount of energy they can provide to offspring and so apes cannot expand brains above what is known as a ‘gray ceiling’ at 600cc (Isler & Van Schaik 2012). Our ancestors broke through this ceiling some 1.5–2 million years ago with the emergence of Homo erectus, with brain volumes more than twice those of chimps today. This suggests that cooperative childcare was already important in Homo erectus society, entailing cooperative eyes and emergent intersubjectivity (Burkart et al 2009). Prosociality, social tolerance, and aversion to inequity on behalf of others, not just self (Burkart et al 2009), fostered by cooperative childcare, would have enabled brain expansion and launched the human career of cumulative cultural transmission (van Schaik & Burkart 2011; van Schaik et al 2012).

Because they required reliable transfers of energy from others to mothers with offspring, increasing brain sizes could only have been favoured in social conditions of reduced tendency to dominance and greater egalitarianism. Competition for nutrient-dense foods and lack of sharing to burdened mothers would result in species with smaller, not larger brain sizes. The level of egalitarianism in Homo lineages can be tracked by measuring brain sizes in these early humans, using the fossil record. Brains could only expand as materially more energy was channelled to females and their offspring. This again implies gendering of the strategies that enabled this to happen. Male dominance, harassment and strategic control of females – surmised by Foley & Gamble (2009) – would have obstructed such unprecedented increases of brain size. Those populations where male dominance, sexual conflict and infanticide risks remained high were least likely to become our ancestors. Instead, our forebears solved the problem of great ape male dominance, harnessing males into routine support of these extraordinarily large-brained offspring.

Among the mechanisms by which mothers gained energy, by recruiting male help, women have evolved a sexual physiology that is levelling and time-wasting (Power et al 2013). Their reproductive signals do not favour males who want to identify fertile females, monopolise the fertile moment and then move on to the next one – a classic strategy for dominant male apes. Concealed and unpredictable ovulation combined with continuous sexual receptivity through almost the whole cycle makes it hard for males to track periods of female fertility (van Schaik et al 2004). A would-be dominant male trying to guard more than one female wastes time guessing about the possible fertility of any cycling female. Guarding her, he misses other opportunities, and other males will be attending to those other sexually receptive females. Continuous sexual receptivity spreads the reproductive opportunities around many males, and hence is levelling from an evolutionary perspective (Marlowe & Berbesque 2012). BaYaka women of the Congo forest express their resistance to male attempts to form harems with the cry: ‘One woman, one penis!’ (Knight and Lewis, 2017:440). These forest hunter-gatherer women demand one man each to support their energy requirements and investment in costly offspring.

African fossils suggest that the last phase of expansion coincided with our speciation (see Power et al 2013:42, Table 1; Watts 2014:212–213, Table 16.1; Hublin et al 2017; Will et al 2021, Fig 1c; Gingerich 2022; Watts in press, SOM A3). Homo sapiens emerged in the African late Middle Pleistocene in two phases of speciation, showing initially a modern flat facial morphology (Hublin et al 2017) followed by evolution of a globularised skull (Neubauer et al 2018; Meneganzin et al 2022). Two key pressures impacted these populations: first, the tendency for increase in brain volume, and second, possible pulses of aridity during the Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 8 and 6 (see Watts in press, SOM A2, A3). The second, environmental pressure acted as a brake on the first. Ancestral African Homo sapiens may have met another version of the ‘gray ceiling’, a constraint on energy available to mothers with pinchpoints in dry-season scarcity of vital nutrients. Dennell and Hurcombe (2024) point to critical impacts on maternal and infant survival during first and third trimester of pregnancy, and the first six months after birth.

Across primate species, seasonality may constrain the evolution of larger brains, as for instance the extreme dry seasons of Madagascar limit available energy for lemur species (apart from aye ayes with specialist mechanisms for extracting larvae) (van Schaik et al 2012). The energy-hungry, fast-growing brains of infants and young children must be supplied every day to avoid energy shortfall which would compromise brain development (Lukas & Campbell 2000; Skoyles 2012). During dry seasons, African game animals are typically very lean. Without fats or carbohydrates, humans cannot survive on protein alone (Speth 2010). ‘Rabbit starvation’ quickly ensues. A novel strategy for access to fats at these lean times could therefore release the brake on brain size.

Watts (2022) proposes a critical role was played by a novel, highly productive hunting strategy – dry-season ambush hunting close to waterholes on moonlit nights. Aligned with the development of accurate throwing weapons (Lombard & Churchill 2023), these new productive strategies could have been mobilised through reverse dominant ritual traditions. Habitual red ochre use from circa 160,000 years ago may offer evidence for such traditions (Dapschaukas et al 2022; Power et al 2024).

The evolution of language

The evolutionary emergence of language involves ‘the very opposite of violence’, in the words of Pierre Clastres (1977:36). Speech, he continues, ‘must be interpreted […] as the means the group provides itself with to maintain power outside coercive violence; as the guarantee repeated daily that this threat is averted’. In Graeber’s terms, speech is a ‘counterpower’ (2004:24–25).

In Debt, Graeber describes ‘baseline communism’ (2011:98) in terms of adhering to a default principle ‘from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs’. This could be understood by biologists investigating the evolution of cooperation as generalised ‘cooperation between strangers’, a fundamental requirement for language. Graeber links this basic attitude of human sociability to language use: ‘Conversation is a domain particularly disposed to communism’ (2011:97). Language as the mutual exploration of each other’s minds requires nonviolent safe space and time to be able to work. Even insults and put downs ‘derive most of their power from the shared assumption that people do not ordinarily act this way’ (2011:97). Conversation as a necessarily consensual process expresses the quintessential opposite of relations of dominance. It relies on the ultimate in intersubjective ability to look through the eyes of the other. A fundamentally egalitarian matrix is the only possible ground for the evolution of language.

Graeber and Wengrow illustrate this relationship of language and egalitarianism with their story of the Huron-Wendat chief, Kandiaronk (2021:49–51). Known as ‘Le Rat’, he was famed for superior sociocognitive linguistic skills. During the 1690s, he became celebrated for arguing jesuits and governorgenerals of New France under the table. If you live in a society where no one can tell anyone else what to do, then, to achieve agreement, you have to argue and persuade, hence the remarkable and well-practised oratorical skills of Native Americans. Subject to arbitrary power, Europeans, by contrast, had to follow orders – not conducive to developing reasoned consensus argument (Graeber & Wengrow 2021:39, 46).

This principle applies as much or even more to the evolutionary emergence of language itself in our ancestral past. It would require a prolonged phase of relative egalitarianism to be established. This constraint refutes the idea that egalitarian origins is ‘a myth’ implying ‘primitive simplicity’. The evolution of each one of these human features is predicated on sophisticated strategies for undermining and periodically neutralising dominance relations. This could be achieved through dynamics of day-to-day counter-dominance in individual interactions, with dramatic or ritualised collective displays of reverse dominance on occasion (Knight & Lewis 2017).

The role of gender

There are strong grounds for seeing gendered strategies playing a central role in the evolution of these features. Babysitting and allocare would not have involved only females, but female strategic needs would have been critical as drivers of mutuality in mind-reading. Similarly, demands of increasing brain sizes and energy costs for mothers would lead to novel, specifically female responses, both coalitionary and cooperative, and in terms of individual female choice. Female ancestors had probably overwhelming influence in any process of ‘self-domestication’ (Hare 2017; Boeckx 2023) through choice of males with reduced reactive aggression. Egalitarian and cooperative childcare coalitions provided contexts for sharing intentions and emotional states. Such unprecedented levels of trust were needed to begin communicating and playing with conventional, shorthand vocalisations – speech (Knight & Lewis 2017).

Linguist Cedric Boeckx (2023), working on interdisciplinary models for the foundation of human language and cognition, argues for social and evolutionary processes of reduced reactive violence (seen as part of the domestication syndrome) with increased social tolerance enabling more exploratory learning. Critical for cumulative culture were social relationships of a certain type, establishing trust in communicative intent. The words of language require a ‘special, safe ecology’ (2023:6). He links their evolutionary emergence to gendered strategies of reverse dominance (2023:7). We could say that the evolution of language itself required an ‘ecology of freedom’.

In the debates on the evolution of egalitarianism, Knauft (1994:182) posed the questions: ‘what role do females play in dominance or counter-dominance, and what is the relationship between counter-dominance and female mate selection?’ The most telling aspect of this, barely considered by Boehm (2001) or Wrangham (2019), would involve gendered resistance to male attempts at sexual coercion or exploitation. Knauft (1994:182, citing Worthman) questioned the intrinsic male bias to models of egalitarianism in evolution. This continues today, founded in Woodburn’s argument (1982:436) that lethal weapons had a levelling tendency among men (eg Gintis et al 2015; Stibbard-Hawkes 2020). Yet female energetic requirements meant they needed above all to ensure newly developed throwing weaponry was put to use effectively by humans against game animals.

Boehm drew mainly on work by Richard Lee with the Kalahari Ju/’hoansi to identify reverse dominance tactics ranging from playful mockery all the way to execution squads. In support of his exclusively male version of the ‘self-domestication’ theory, Wrangham (2019) especially focuses on execution squads disposing of violent and obnoxious individuals. But these are rare events, perhaps seen once in a decade in hunter-gatherer populations. The much more workaday tactics of laughter, mimickry and levelling reveal the gendered dimension of reverse dominance. Women, often older women, individually and collectively, are central to bringing men down with a bump (Lewis 2014).

Jerome Lewis (2014:230) has described the key BaYaka technique of moadjo that involves a kind of pantomime or stand-up comedy, where an older woman begins to mime and caricature someone’s stupid behaviour, drawing a crowd. This quickly becomes hilarious as onlookers join in and copy her moves, with encouraging noises and comments. No one speaks any name until, eventually, the target gets it that he (usually) is the cause of all the laughter. Then he storms off, or, seeing what an idiot he’s been, laughs along, so rejoining the community. Either way, everything is forgiven and forgotten – no executions necessary. Lewis (2014:230) explains:

Mbendjele men only tolerate such explicit criticism from women. If men do this, it easily leads to serious fights. Widows have a special place in this type of humorous but directed criticism and are expected to do this in front of the whole camp at moments of high tension or when someone has committed a grave error. A good performer will succeed in calming the atmosphere by allowing everyone to laugh at themselves. Indeed, if the person being criticized is present, the moadjo will only end when they laugh publicly too. However, on realizing that they are becoming the center of the camp’s mirth, the wrongdoer often flees and hides in the forest until things calm down.

One of the finest ethnographies of reverse dominance comes from Daša Bombjaková. She documented and participated in moadjo, describing three different types or contexts (2018:214–215): i) normative, reenactments of people’s stupid behaviour by one or more women, to get the target to ‘see their own silly behaviour’; ii) coalitionary, among a bunch of women, more for fun and entertainment purposes when the target is absent, but solidarising and expressing shared opinion; and iii) ‘gender competition’ moadjo, a fully ritualised response mocking men in general (especially male sexuality) or challenging any male insult to women as a group. Bombjaková sees this as a female militant, reverse dominance strategy. Examples range from the common practice of female ngoku forest-spirit ceremony to dynamic reassertion of ‘female values’ when needed (2018:234).

Some such levelling technique as moadjo may have deep roots in our ancestry, linked to the evolution of capacities of intersubjectivity – seeing ourselves as others see us. Moadjo does not rely on language but rather on mimesis (Donald 1991). It offers a stepping-stone both towards ritual and to language. In one case of normative moadjo, Bombjaková talks of a performance making the target (she, in this case) ‘see her silly actions right in front of her eyes’ (2018:224). The process of exaggerated repetition of pantomime sequences gives a potential mechanism for scaffolding language emergence. Parts of the action sequence could be shorthanded into increasingly language-like tags, with accompanying noises. In these situations, to the extent that the target individual laughs at themselves, participants move towards sharing a shorthand reference or token for a concept – a ‘word’ sung out as part of the action – at the same time moving together in sharing moral emotions. Shared laughter maintains the egalitarian ethos vital to the process.

In coalitionary and gender-competition versions, moadjo tends towards ritual, the first as a kind of coordinating rehearsal for the occasions when full-scale sex militancy is needed. While the first may appear improvised ‘just for fun’, it primes women’s solidarity within particular coalitions. At a hint of threat or challenge from men, the entire women’s community coalesces in reverse dominance ritual. Women’s ngoku spirit ensures periodic neutralising of male dominance in any form, through hilarious re-enactment of men’s sexual antics. This is women’s weaponry, but it’s not lethal. The test of being able to see oneself through the eyes of others, and of being able to laugh at oneself would be a major aspect of female selection for reduced reactive aggression.

Chris Knight (1998; and see Knight & Lewis 2017) argues for the necessary coevolution of ritual and speech, with ritual acting to create unprecedented levels of trust within a speech community. Such trust allows shorthand, conventional vocal signals to be heard as intentionally honest. The shared emotional experience of costly ritual (Alcorta & Sosis 2005) intensifies levels of trust within the group and generates a ‘shared virtual world’ (Knight & Lewis 2017) to which the cheap, tokenistic signals of speech can refer. At the same time, high-cost ritual performance is designed to impress outsiders to the group, overcoming potential conflicts of interest. A moadjo-like starting point of playful mimickry can evolve both the words and grammar within the ingroup, and the costly ritual action confronting an outgroup. Gender formed the likely initial boundaries to groups. African hunter-gatherer women to this day mount periodic reverse dominant displays in powerful intergenerational coalitions (Kisliuk 1998; Finnegan 2013; Power 2015; 2017; Power et al 2024). The shared structures of these gender rituals imply considerable time-depth (Power 2017; Liebenberg 2020; Watts in press).

Leaving aside Africa

According to these arguments, no egalitarianism would emerge without a fundamental gender egalitarianism asserted in ritual performance. Far from ‘simplicity’, this egalitarian political process gave rise to the cutting edge of creative cultural intelligence, resulting in playful, imaginative, shared human worlds. Attempts at control and dominance would lead to evolutionary disadvantage. Simply put, Middle Pleistocene populations with more hierarchical tendencies were the least likely to have become language-speaking, larger-brained, singing, healing, dancing ancestors of Homo sapiens.

Graeber and Wengrow treat Africa’s role in human cultural origins in a few sketchy pages (2021:80–83). They claim: ‘The only thing we can reasonably infer about social organization among our earliest ancestors is that it’s likely to have been extraordinarily diverse’. (2021:82) Contrary to this guesswork, I argue that the populations ancestral to everyone alive today were highly constrained to be egalitarian. Without this no language, no ritual or symbolic domain would emerge; no large brains; no humanlike kinship and morality (Power et al 2024).

Although early African H. sapiens populations appear morphologically diverse, they also seem remarkably similar in terms of shared cultural traditions the length and breadth of the continent. In a meta-analysis of 100 African sites, Rimtautas Dapschauskas and colleagues ‘try to answer the question of when and where habitual ochre use emerged and what significance this had for the development of ritual behavior during the Middle Stone Age’ (2022:234). They use methods based on time-averaging to identify three continent-wide distinct phases of ochre use: an initial phase 500–330 thousand years ago (ka); an emergent phase from 330–160 ka; and an habitual phase from 160–140 ka. At each phase, the number of sites with ochre increases; the ratio of sites with ochre compared to those with only stone artefacts shows increasing intensity of ochre use. It becomes habitual cultural practice in South, East and North Africa from 160 ka when a third of sites contain ochre.

Importantly, the authors ‘view […] habitual ochre use as a proxy for the emergence of regular collective rituals’ (2022:241). While ochre definitely can have functional uses, ritualised, visual display appears primary: Middle Stone Age (MSA) ochres reflect costly and repetitive behaviours, including long-distance procurement and intentional colour selection for reds (2022:236). Red residues are found on shell beads when these appear later in sites from South to North Africa at Blombos, Taforalt and Bizmoune, now dated at older than 140,000 years (Sehaaseh et al 2021). This likely resulted from body paint on skin or deliberate colouring. In sum, Dapschauskas and colleagues ‘view a large proportion of ochre finds from the MSA as the material remains of past ritual activity’ (2022:238). They take ‘the emergence of habitual collective rituals’ to be ‘one important prerequisite for the evolution of symbolic communication’ (2022:244).

Three decades ago, the authors of the Female Cosmetic Coalitions hypothesis (Knight et al 1995) took the position that regular occurrence of ochre marked ritual activity critical to the emergence of symbolic cognition. They argued that reproductive stress on mothers of increasingly large-brained offspring drove signalling strategies in female coalitions. Women simply needed more energy to meet the extra metabolic costs of those large brains, and they turned on the leisured sex, males, to provide more reliably. Their demands for increased investment from men exploited the key signal of menstruation. Why? Because when most women would be pregnant or breastfeeding, menstrual cycling implies imminent fertility and, in a Darwinian world, immediately grabs attention. Women created cosmetic rituals to ‘bleed’ together, resisting the advances of any male who tried to single out fertile women from the pregnant/ nursing mothers who most needed energy. This was both protosymbolic action – with a group of women sharing in imaginary ‘blood’ or ‘fertility’ – and also protomoral, establishing ‘taboos’ on bleeding bodies. Above all, it provided a template for reverse dominant gender ritual.

At the time, Knight and colleagues proposed: ‘Reproductive stress motoring “sham menstruation” may have become most acute in the period 160–140 Kya, the height of the Penultimate Glacial cycle’ (1995:81). There is now understood to be greater complexity of factors influencing the African climate (Kaboth-Bahr et al 2021). More evidence is needed to assess when and where exactly the later phase of brain expansion was impacted by dry-season scarcity stress. This can be compared with the results of Dapschauskas et al (2022:279, Figure 5, and 282, Figure 9).

Given an archaeological timeframe for the emergence of habitual ritual traditions during the second phase of our speciation as a dynamic form of reverse gender dominance, how does this perspective reflect on the key question posed by Graeber and Wengrow: ‘How did we get stuck?’ (2021:112). They claim this is the ‘real’ question rather than seeking the origin of social inequality. But their excellent question is hard to address without first grasping how we got to be equal. Leaving aside Africa, they focus on the European Upper Palaeolithic some 30,000 years ago for their earliest evidence. They advance an intriguing interpretation of elaborate burials in highly seasonal environments (2021:102–104) as relics of a seasonally flexible social structure, switching between hierarchy and egalitarianism.

This oscillation model resembles the politics of ‘bodies in motion’ proposed earlier by Finnegan (2008, 2013), of a ‘pendulum’ of power, a push–pull motion between ritual groups of women and men among Central African Forest people. Only by keeping bodies moving in dialogue can fixity of hierarchy be resisted. Women won’t let power get stuck. Their coalitions are ‘fizzing’ and ‘churning’, setting rhythm, dialogue and dances going. But rather than any seasonal oscillation, this is periodic on women’s terms, connecting with lunar and menstrual cycles and idioms (Power 2022). Finnegan asks: ‘what are the implications for a society when the story that is ritualized through bodily comportment highlights female reproductive anatomy, female bodily fluids, and female desire, and refracts these back to the community as cultural power?’ (2013:702)

It seems that Graeber and Wengrow approach close but don’t see that this oscillatory, periodic motion is one way that egalitarianism works – ‘communism in motion’ as Finnegan has called it (2008:218). The nimble lunar periodicity typical of African hunter-gatherer ritual action prevents hierarchy from taking root; slower seasonal periodic switches, by contrast, allow power to become entrenched.

Conclusion

In The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow attack the idea that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were necessarily egalitarian, arguing that this is a ‘myth’ making them out as ‘simple’ and ‘childlike’. By contrast, hunter-gatherer anthropologists, with evolutionary psychologists and anthropologists, argue that maintaining egalitarian relations is cognitively, emotionally and intersubjectively complex and socially sophisticated.

Egalitarianism is seen as a foundational requirement of the ratchet effect of cumulative cultural evolution (Whiten 1999; Migliano & Vinicius 2021). Human intersubjectivity evolved through gendered strategies of collective childcare (Hrdy 2009) giving rise to increased social tolerance and inequity aversion on behalf of others (Burkart et al 2009). Graeber and Wengrow (2021:129) are wary of Woodburn pointing to immediate-return hunter-gatherers as true egalitarians, saying this implies only the ‘very simplest foragers’ can possibly achieve equality, leaving the rest of us stuck. An alternative perspective is that it took almost a million years of forging human nature throughout the Middle Pleistocene. Egalitarian relations are far from ‘simple’; they made us human, and the evolved sociocognitive skills are unlikely to disappear overnight.

This article addresses the main evolutionary models for egalitarianism, and discusses derived features of Homo sapiens – anatomical, psychological and cognitive – that required prolonged periods of egalitarianism to emerge in our species. Female strategies and cultural power would have been central to these processes, notably in periodic, reverse dominant ritual practice. Egalitarian relations, between genders and between generations, were crucial to making us the symbolic species we are.

References

Aiello, LC & Key, C 2002. The energetic consequences of being a Homo erectus female. American Journal of Human Biology 14:551–565.

Aiello, LC & Wheeler, P 1995. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Current Anthropology 36:199–221.

Alcorta, CS & Sosis, R 2005. Ritual, emotion, and sacred symbols: the evolution of religion as an adaptive complex. Human Nature 16:323–359.

Biesele, M 2023. Once upon a time is now: a Kalahari memoir. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Bird-David, N 2020. A peer-to-peer connected cosmos: beyond egalitarian/hierarchical hunter-gatherer societies. L’Homme 236:77–106.

Boeckx, C 2023. What made us ‘hunter-gatherers of words’. Frontiers in Neuroscience 17: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1080861.

Boehm, C 2001. Hierarchy in the forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bombjaková, D 2018. The role of institutions of public speaking, ridicule, and play in cultural transmission among Mbendjele BaYaka forest hunter-gatherers. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London.

Boyd, R, & Richerson, P 2022. Large-scale cooperation in small-scale foraging societies. Evolutionary Anthropology 31:175–198.

Burkart, JM, Hrdy, SB & van Schaik, CP. 2009. Cooperative breeding and human cognitive evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology 18:175–186.

Byrne, R & Whiten, A (eds) 1988. Machiavellian intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caspar, KR, Biggemann, M, Geissmann, T & Begall, S 2021. Ocular pigmentation in humans, great apes, and gibbons is not suggestive of communicative functions. Scientific Reports 11:12994.

Chaudary, N, Salali, GD & Swanepoel, A 2023. Sensitive responsiveness and multiple caregiving networks among Mbendjele BaYaka hunter-gatherers: potential implications for psychological development and well-being. Developmental Psychology https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001601.

Clastres, P 1977. Society against the state. Translated by R Hurley & A Stein. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dapschauskas, R, Göden, MB, Sommer, C & Kandel, AW 2022. The emergence of habitual ochre use in Africa and its significance for the development of ritual behavior during the Middle Stone Age. Journal of World Prehistory 35:233–319.

Dennell, R & Hurcombe, L 2024. How and why is H. sapiens so successful? Quaternary Environments and Humans https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2024.100006.

Donald, M 1991. Origins of the modern mind: three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dyble, M. 2020. The impact of equality in residential decision making on group composition, cooperation and cultural exchange. In Moreau, L (ed) Social inequality before farming? Multidisciplinary approaches to the study of social organisation in prehistoric and ethnographic hunter-gatherer-fisher societies. Cambridge: MacDonald Institute Monograph Series:51–57.

Dyble, M, Salali, G, Chaudhary, N, Page, A, Smith, D, Thompson, J, Vinicius, L, Mace, R & Migliano, A 2015. Sex equality can explain the unique social structure of hunter-gatherer bands. Science 348:796–798.

Erdal, D & Whiten, A 1994. On human egalitarianism: an evolutionary product of Machiavellian status escalation? Current Anthropology 35:175–183.

Erdal, D & Whiten, A 1996. Egalitarianism and Machiavellian intelligence in human evolution. In Mellars, P & Gibson, K (eds) Modelling the early human mind. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs:139–150.

Finnegan, M 2008. The personal is political: Eros, ritual dialogue and the speaking body in Central African hunter-gatherer society. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Finnegan, M 2013. The politics of Eros: ritual dialogue and egalitarianism in three Central African hunter-gatherer societies. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19:697–715.

Foley, RA & Gamble, C 2009. The ecology of social transitions in human evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 364:3267–3279.

Foley, RA & Lee, PC 1991. Ecology and energetics of encephalization in hominid evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London 334:223–232.

Forss, S & Willems, E 2022. The curious case of great ape curiosity and how it is shaped by sociality. Ethology 128:552–563.

Fried, MH 1967. The evolution of political society. New York: Random House.

Gingerich, PD 2022. Pattern and rate in the Plio-Pleistocene evolution of modern human brain size. Scientific Reports 12:11216.

Gintis, H, van Schaik, CP & Boehm, C 2015. Zoon politikon: the evolutionary origins of human political systems. Current Anthropology 56:327–353.

Glowacki, L & Lew-Levy, S 2022. How small-scale societies achieve large-scale cooperation. Current Opinion in Psychology 44:44–48.

Graeber, D 2004. Fragments of an anarchist anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Graeber, D 2011. Debt: the first 5000 years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Graeber, D & Wengrow, D 2021. The dawn of everything. London: Allen Lane.

Grossmann, T 2017. The eyes as windows into other minds: an integrative perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science 12:107–121.

Hare, B. 2017. Survival of the friendliest: Homo sapiens evolved via selection for prosociality. Annual Review of Psychology 68:155–186.

Hewlett, B & Lamb, M (eds) 2005. Hunter gatherer childhoods: evolutionary, developmental and cultural perspectives. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Hrdy, SB 2009. Mothers and others: the evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Harvard: Belknap Press.

Hublin, J-J, Ben-Ncer, A, Bailey, SE, Freidline, SE, Neubauer, S, Skinner, MM, Bergmann, I, Le Cabec, A, Benazzi, S, Harvati, K & Gunz, P 2017. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 546:289–292.

Isler, K & van Schaik, CP 2012. How our ancestors broke through the gray ceiling: comparative evidence for cooperative breeding in early Homo. Current Anthropology 53, S6, Human biology and the origins of Homo (December):S453–S465.

Jang, H, Janmaat, KRL, Kandza, V & Boyette, AH 2022. Girls in early childhood increase food returns of nursing women during subsistence activities of the BaYaka in the Republic of Congo. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 289:20221407.

Kaboth-Bahr, S, Gosling, WD, Vogelsang, R, Bahr, A, Scerri, EML, Asrat, A, Cohen, AS, Düsing, W, Foerster, V, Lamb, HF, Maslin, MA, Roberts, HM, Schäbitz, F & Trauth, MH 2021. Paleo-ENSO influence on African environments and early modern humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 118:e2018277118.

Kano, F, Kawaguchi, Y & Hanling, Y 2022. Experimental evidence that uniformly white sclera enhances the visibility of eye-gaze direction in humans and chimpanzees.

eLife 11:e74086.

Kisluik, M 1998. Seize the dance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Knauft, B 1991. Violence and sociality in human evolution. Current Anthropology 32:391–428.

Knauft, B 1994. Comment on Erdal, D & Whiten, A. On human egalitarianism: an evolutionary product of Machiavellian status escalation? Current Anthropology 35:175–183.

Knight, C 1998. Ritual/speech coevolution: a solution to the problem of deception. In Hurford, JR, Studdert-Kennedy, M & Knight, C (eds) Approaches to the evolution of language: social and cognitive bases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:68–91.

Knight, C & Lewis, J 2017. Wild voices: mimicry, reversal, metaphor and the emergence of language. Current Anthropology 58:435–453.

Knight, C, Power, C & Watts, I 1995. The human symbolic revolution: a Darwinian account. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 5:75–114.

Kobayashi, H & Kohshima, S 2001. Unique morphology of the human eye and its adaptive meaning: comparative studies on external morphology of the primate eye. Journal of Human Evolution 40:419–435.

Kraft, TS, Cummings, DK, Venkataraman, VV, Alami, S, Beheim, B, Hooper, P, Seabright, E, Trumble, BC, Stieglitz, J, Kaplan, H, Endicott, KL, Endicott, KM & Gurven, M 2023. Female cooperative labour networks in hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 378:2021.0431.

Kuzawa, CW, Chugani, HT, Grossman, LI, Lipovich, L, Muzik, O, Hof, PR, Wildman, DE, Sherwood, CC, Leonard, WR & Lange, N 2014. Metabolic costs and evolutionary implications of human brain development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111:13010–13015.

Lee, RB 1982. Politics, sexual and non-sexual, in an egalitarian society. In Leacock, E and Lee RB (eds) Politics and history in band societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:37–59.

Lewis, J 2014. Egalitarian social organization: the case of the Mbendjele BaYaka. In Hewlett, BS (ed) Hunter-gatherers of the Congo Basin: cultures, histories and biology of African Pygmies. New Brunswick: Transaction:219–243.

Liebenberg, D 2020. Menstruation, moon and the hunt. Hunter Gatherer Research 6.3–4 (2023 [for 2020]):217–246.

Lombard, M & Churchill, S 2023. Revisiting Middle Stone Age hunting at ≠Gi, Botswana: a tip cross-sectional area study. Southern African Field Archaeology 17:https://doi.org/10.36615/safa.1.1138.2022.

Lukas, WD & Campbell, BC 2000. Evolutionary and ecological aspects of early brain malnutrition in humans. Human Nature 11:1–26.

Marlowe, FW & Berbesque, JC 2012. The human operational sex ratio: effects of marriage, concealed ovulation, and menopause on mate competition. Journal of Human Evolution 63:834–842.

Mayhew, JA & Gómez, JC 2015. Gorillas with white sclera: a naturally occurring variation in a morphological trait linked to social cognitive functions. American Journal of Primatology 77:869–877.

Mearing, AS, Burkart, JM, Dunn, J, Street, SE & Koops, K 2022. The evolutionary drivers of primate scleral coloration. Scientific Reports 12:14119.

Meneganzin, A, Pievani, T & Manzi, G 2022. Pan-Africanism vs. single-origin of Homo sapiens: putting the debate in the light of evolutionary biology. Evolutionary Anthropology 31(4):199–212.

Migliano, AB & Vinicius, L 2021. The origins of human cumulative culture: from the foraging niche to collective intelligence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 377: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0317.

Miller, JM & Wang, YV 2022. Ostrich eggshell beads reveal 50,000-year-old social network in Africa. Nature 601:234–239.

Neubauer, S, Hublin, J-J & Gunz, P 2018. The evolution of modern human brain shape. Science Advances 4:eaao5961.

Power, C 2015. Hadza gender rituals – Epeme and Maitoko – considered as counterparts. Hunter Gatherer Research 1:333–358.

Power, C 2017. Reconstructing a source cosmology for African hunter-gatherers. In Power, C, Finnegan, M & Callan, H (eds) Human origins: contributions from social anthropology. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books:180–203.

Power, C 2022. Lunarchy: the original human economics of time. In Silva, F & Henty, L (eds) Solarizing the moon: essays in honour of Lionel Sims. Oxford: Archaeopress:3–26.

Power, C, Finnegan, M & Callan, H 2017. Introduction. In Power, C, Finnegan, M & Callan, H (eds) Human origins: contributions from social anthropology. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books:1–34.

Power, C, Sommer, V & Watts, I 2013. The seasonality thermostat: female reproductive synchrony and male behaviour in monkeys, Neanderthals and modern humans. PaleoAnthropology 2013:33–60.

Power, C, Watts, I & Knight, C 2024. The symbolic revolution: a sexual conflict model. In Gontier, N, Sinha, C & Lock, A (eds) Oxford handbook of human symbolic evolution Oxford: Oxford University Press:289–310.

Reckin, R, Lew-Levy, S, Lavi, N, & Ellis-Davies, K 2020. Mobility, autonomy, and learning: Could the transition from egalitarian to non-egalitarian social structures start with children? In Moreau, L (ed) Social inequality before farming? Multidisciplinary approaches to the study of social organisation in prehistoric and ethnographic hunter-gatherer-fisher societies. Cambridge: MacDonald Institute Monograph Series:33–50.

Sehasseh, EM, Fernandez, P, Kuhn, S, Stiner, M, Mentzer, S, Colarossi, D, Clark, A, Lanoe, F, Pailes, M, Hoffmann, D, Benson, A, Rhodes, E, Benmansour, M, Laissaoui, A, Ziani, I, Vidal-Matutano, P, Morales, J, Djellal, Y, Longet, B, Hublin, J-J, Mouhiddine, M, Rafi, F-Z, Worthey, KB, Sanchez-Morales, I, Ghayati, N & Bouzouggar, A 2021. Early Middle Stone Age personal ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco. Science Advances 7:eabi8620.

Shultziner, D, Stevens, T, Stevens, M, Stewart, BA, Hannagan, RJ, & Saltini-Semerari, G 2010. The causes and scope of political egalitarianism during the Last Glacial: a multi-disciplinary perspective. Biology & Philosophy 25:319–346.

Singh, M & Glowacki, L 2022. Human social organization during the Late Pleistocene:

beyond the nomadic-egalitarian model. Evolution and Human Behavior 43:418–431.

Skoyles JR 2012 Human neuromaturation, juvenile extreme energy liability, and adult cognition/cooperation. Nature Precedings https://doi.org/10.1038/ npre.2012.7096.1.

Solway, J (ed) 2006. The politics of egalitarianism: theory and practice. New York: Berghahan Books.

Speth, J 2010. The paleoanthropology and archaeology of big-game hunting: protein, fat, or politics? Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. New York: Springer.

Stibbard-Hawkes, DNE 2020. Egalitarianism and democratized access to lethal weaponry: a neglected approach. In Moreau, L (ed) Social inequality before farming? Multidisciplinary approaches to the study of social organisation in prehistoric and ethnographic hunter-gatherer-fisher societies. Cambridge: MacDonald Institute Monograph Series:83–101.

Tomasello, M & Rakoczy, H 2003.What makes human cognition unique? From individual to shared to collective intentionality. Mind and Language 18:121–147.

Tomasello, M, Carpenter, M, Call, J, Behne, T & Moll, H. 2005. Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28:675–691.

Tomasello, M, Hare, B, Lehmann, H & Call, J 2007. Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: the cooperative eye hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution 52:314–320.

van Schaik, CP & Burkart, JM 2011. Social learning and evolution: the cultural intelligence hypothesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 366:1008–1016.

van Schaik, CP, Isler, K & Burkart, JM 2012. Explaining brain size variation: from social to cultural brain. Trends in Cognitive Science 16:277–284.

van Schaik, CP, Pradhan, GR & Tennie, C 2019. Teaching and curiosity: sequential drivers of cumulative cultural evolution in the hominin lineage. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 73(2):https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2610-7.

van Schaik, CP, Pradhan, GR & Van Noordwijk, MA 2004. Mating conflict in primates: infanticide, sexual harassment and female sexuality. In Kappeler, PM & van Schaik, CP (eds) Sexual selection in primates: new and comparative perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:131–150.

Venkataraman, VV 2022. The origins of human society are more complex than we thought. The Conversation. 2 November. https://theconversation.com/ the-origins-of-human-society-are-more-complex-than-we-thought-179137.

Watts, I 2014. The red thread: pigment use and the evolution of collective ritual. In Dor, D, Knight, C & Lewis, J (eds) The social origins of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press:208–227.

Watts, I 2022. Hunting by the moon in human evolution. In Silva, F & Henty, L (eds) Solarizing the moon: essays in honour of Lionel Sims. Oxford: Archaeopress:27–52.

Watts, I in press. Blood symbolism at the root of symbolic culture? African huntergatherer perspectives. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Whiten, A 1999. The evolution of deep social mind in humans. In Corballis, M & Lea, SEG (eds) The descent of mind: psychological perspectives on hominid evolution.

Oxford: Oxford University Press:173–193.

Whiten, A & Erdal, D 2012. The human socio-cognitive niche and its evolutionary origins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 367:2119–2129.

Wiessner, P 1982. Risk, reciprocity and social influences on !Kung San economics. In Leacock, E & Lee RB (eds) Politics and history in band societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:61–84.

Wiessner, P 2002. Hunting, healing, and hxaro exchange: a long-term perspective on !Kung (Ju/’hoansi) large-game hunting. Evolution and Human Behavior 23:407–436.

Wiessner, P 2022. Hunter-gatherers: perspectives from the starting point. Cliodynamics 3:https://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio0057263.

Will, M, Krapp, M, Stock, JT & Manica, A 2021. Different environmental variables predict body and brain size evolution in Homo. Nature Communications 12:4116.

Woodburn, J 1980. Hunters and gatherers today and reconstruction of the past. In Gellner, E (ed) Soviet and Western anthropology. New York: Columbia University:95–118.

Woodburn J 1982. Egalitarian societies. Man NS 17:431–451.

Woodburn, J 1998. ‘Sharing is not a form of exchange’: an analysis of property sharing in immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies. In Hann, CM (ed) Property relations: renewing the anthropological tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:48–63.

Woodburn, J 2005. Egalitarian societies revisited. In Widlok, T & Tadesse, WG (eds) Property and equality (vol 1). New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books:18–31.

Wrangham, R 2019. The goodness paradox: the strange relationship between virtue and violence in human evolution. New York: Pantheon.

Before The Dawn of Everything{3}

Ian Watts

20 Aristophanous, Athens 105 54, Greece ochrewatts@hotmail.com