Various

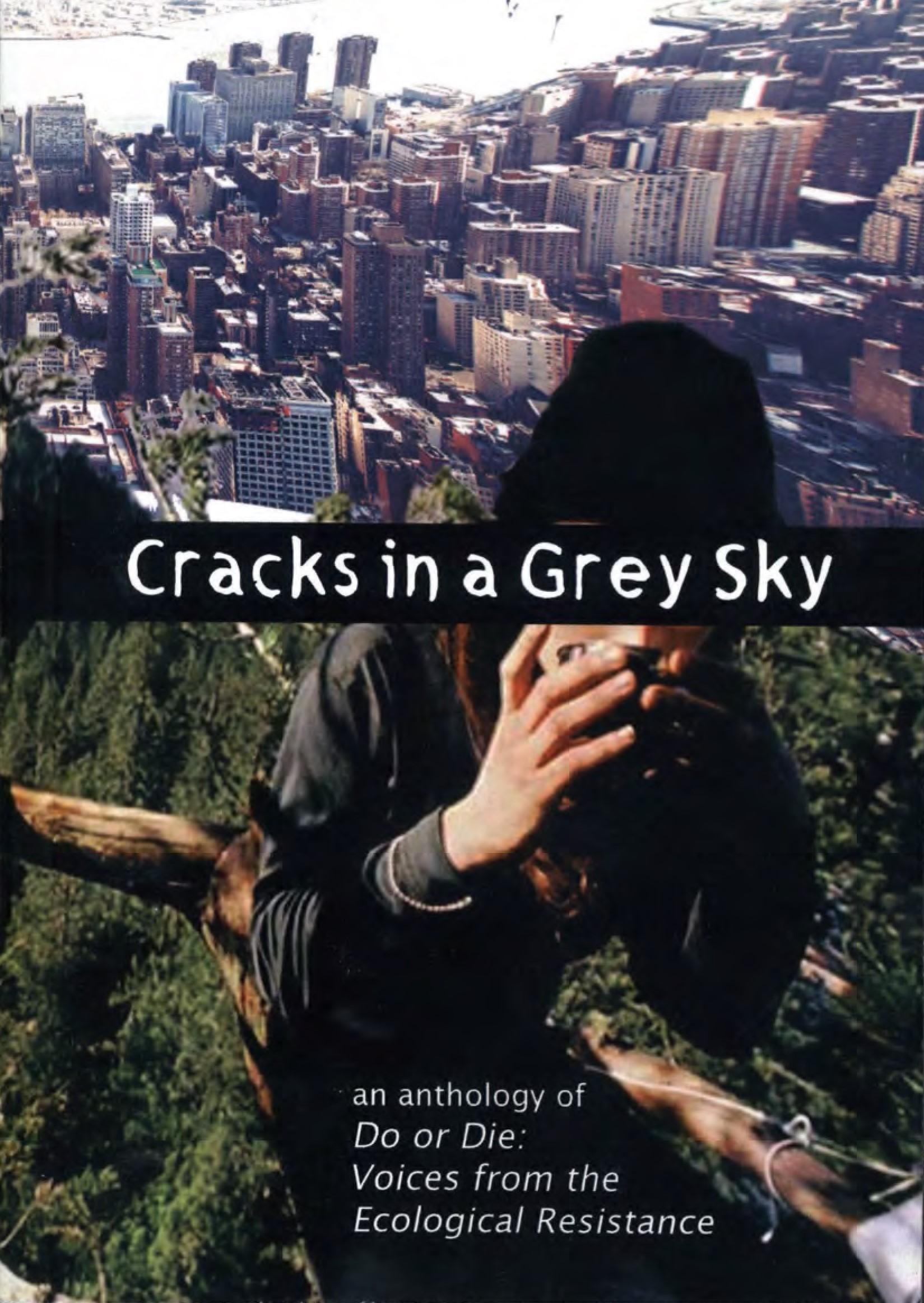

Cracks in a Grey Sky: An Anthology of Do or Die

Voices from the Ecological Resistance

Supporting Rebellion Beyond the Core

The Day They Drove Twyford Down! (from issue 1)

A tribe member describes Yellow Wednesday!

Trees for Life: The Amazon on our Doorstep (from issue 2)

A Letter from Scotland (from issue 3)

Car Chases, Sabotage, and Arthur Dent (From issue 3)

April 21 Second day of the Salisbury inquiry

News From the Autonomous Zones (from issue 4)

The Start of the Action: 13th September: November 1, 1993

The Chestnut Tree: November 2—December 7, 1993

Black And Blue Tuesday: December 7

Actions, Actions and Yet More Actions

Site Invasions & Grappling Hooks

Biodiversity and the British Isles (from issue 4)

An Open Letter to the Minister for Transport

Shoreham: Live Exports and Community Defence (from issue 5)

Reports and Thoughts on the Action in Derbyshire

“All this lurking about in the dark inspired a lot of giggling.”

“What were the aims of the action?”

“Re-open the deep mines? Over my dead body!”

The New Luddite War (from issue 8) We Will Destroy Genetic Engineering!

Elite Technology “Weaponry for the Class War

Growing the Global Land Community

My First Genetic Crop Trashing (from issue 8)

Sabbing Shell: Office Occupation A-Go-Go! (from issue 8)

Take a Sad Song and Make it Better? (from issue 8)

Ecological Restoration in the UK

Conservation and the Control Complex

Farming for Wildlife, Farming of Wildlife

The National Forest and the Community Forests-Managing People and Nature

Community, Partnership, and All That jazz

Bashing the GE-nie Back in the Bottle (from issue 9)

Borders No Barrier to Sabotage

Hurricane Sabotage Hits GM Harvest

Derek Wall Fingers the Green Nazis (from issue 1)

Critical Mass: Reclaiming Space and Combating the Car (from issue 5)

Reclaim the Streets (from issue 6)

Street Party as Public Meeting

The Street Party of Street Parties

Stop Making Sense: Direct Action and Action Theatre (from issue 6)

Lights, Camera... Activism! (from issue 7)

Friday June 18th, 1999 (from issue 8)

Contradictions Of Globalisation

Good Ideas Spread Like Wildfire

The Day Gets Nearer-The State Prepares...

The Day Gets Even Nearer-We Prepare...

Desire is Speaking: Utopian Rhizomes (from issue 8)

Running to Stand Still (from issue 9)

Globalisation, Blagging, and the Dole

The New Deal and the Welfare Reform Act

Space Invaders: Rants about Radical Space (from issue 10)

Earth First! and Tribalism: A Lesson from Twyford Down (from issue 2)

Direct Action Six Years Down the Road (from issue 7)

Action Stations! (from issue 9)

Down with the Empire, Up with the Spring! From issue 10)

Part One: Recent Pre-History

An Insurgency of Dreams

Victoria, Outstanding Preservationist and Great American.

From the Ashes ... Twyford Rising!

Land Struggle Period (1993–1998)

Welcome to the Autonomous Zones

Progress, Yuck-Time to Go Back to the Trees

A Shift from the Local to the Global

Consolidation and Global Resistance Period (1998–2002)

Local Consolidation and Outreach

The Struggle is Global, The Struggle is Local

II. Putting Our Thumb in the Dam

The Mediterranean Red Alert Areas

Some (Don’t) Like it Hot(spot)

(Counter) Revolutionary Rainy Day Reads

Peasants and the Transitional Class

An Introduction

It’s strange to put together a collection of articles from a publication that has been defunct for 13+ years and from nearly 9000 km away. Do or Die, Voices from the Ecological Resistance filled a void that US publications (Live Wild or Die!, Green Anarchy, and Black Seed) have attempted, in their ways, to fill but with nowhere near the quality or quantity of the original. Do or Die (DoD) was the expression of a singular moment by strong writers who agreed about how to approach and discuss a high point of ecological resistance. Here I want to contextualize the struggles discussed in DoD, to speak to the parallels between that time and our current moment, to take seriously the critique and proposals in the paper generally and in “Down with the Empire, Up with the Spring” and “The Four Tasks” specifically. Ultimately we want to introduce a new generation of warriors to the intelligent approach presented in DoD nearly 20 years ago and discuss how this approach is still relevant today.

The Project and Audience

DoD was produced by and largely aimed at a few hundred people in the UK eco scene. Although it had a wider circulation than this, it was largely produced with this audience in mind. But, DoD has also been really liked by all sorts of other people who often didn’t like each other at all. For example lots of more traditional anarchist communists really liked DoD, as did lots of conservationists—the magazine was big enough that very few people read all of it—people just read the bits they liked and ignored the rest. We’d get comments from more traditional anarchists saying that they really liked it, but it was a shame about the articles about beaver restoration or Native American spirituality. And then we’d get almost exactly opposite comments from other people who liked the beavers but weren’t so into class struggle.

—From the EF! postmortem interview circa 2006

DoD was a pre-Internet project and we can only mourn the differences between then and now. Today print publications—that rare and dying breed—cannot accept contradiction or lack of coherence. When they exist at all it tends to be for a small group of true believers, rather than a broad audience of fellow travelers, which is what DoD eventually pulled together. The idea of having something of value to share with your ideological opponents seems increasingly rare within radical politics. There is no more kumbaya as we clamor for smaller and smaller crumbs from a body politic that has a decreasing appetite for the big dreams and declarations about what is ahead, from radicals who are barely able to demonstrate ambulation and mastication (much less simultaneity).

DoD had dozens of contributors each issue. While that is also true for the Earth First! Journal here in the US, DoD, in addition to having commentary based on first-person observation and testimonial (especially as the journal grew in size in the last four issues—issue 10 was nearly 400 pages long), also had lengthy theoretical works. EF! barely has theoretical texts at all, and what there are tend to be short and ranty rather than the massive accomplishment of the pieces “Down with the Empire, Up with the Spring” (DwtE) and “The Four Tasks” (TFT), and even smaller but still engaging ones like the pieces on Critical Mass, Action Theater, and the impact of the dole on activism. That kind of effort has to nurtured and celebrated to find its pace.

It’s also worth noting the decision to shut down the project rather than hand it to the next generation. As they make clear, it wasn’t for lack of relevance or reader enthusiasm. Clearly the same problems and even some of the efforts and solutions offered by DoD make sense to a new generation (hence this collection). But each new generation has to find their own voice, to express even old problems in a way that makes sense to new ears, and dusty old projects (think Rolling Stone) really do tend to stink up the room.

Road Building

What DoD told us about the UK—and about how direct action against the mega-machine looks different when away from forests and wilderness—was wonderful. The imagery and storytelling of road resistance seems like something out of science fiction, not a British parallel to tree sitting and its accompanying culture. In the US the road-protest scene is arguably more needed than it is in the UK, but apart from a few, meager protests (I-69, Loop 202 in AZ, etc), the US innovation seems to be having protests ON freeways rather than efforts against their construction in the first place.

The struggle against the M11 link was inspiring on a number of levels. In particular the imagery of tunnels to burrow under and befuddle construction was amazing. The growth of road-building protests in the 90s seemed so much more salient to the everyday life of someone in civilization, rather than tree-spiking and -sitting in far-off locales. The protest against roads seemed like the right kind of action to come from a country that had so little official wildness left to fight for.

Clearly the fight for the Earth is complex and the war against roads was lost, or perhaps just the battle, although the protestors doubled the cost of the M11 link (which eventually became the ninth most congested road in the UK), and ended, in embryo, similar road-building attempts (the M12 was cancelled on first review). The fight against such an existential opponent roads are the primary circulation system of capitalism-was a worthy one, but it’s hard to believe that anyone involved ever believed that this fight was enough: necessary, but not sufficient. But the grind of an enormous campaign (the Newbury campaign was attempting to stop construction on a nine-mile piece of land, every day, for months) meant that bigger issues could not be debated-exhaustion, drinking, and politics would not allow for it.

The story of roads is inspirational and a great piece of UK EF! cultural currency but ultimately an open wound—the gap between building a movement of the disparate forces that engage in these forms of struggle and the motivation of those groups being ephemeral and contradictory.

Winning and Losing

Basically what happened within EF! was that we won. DoD and the political perspective it represented was relatively unpopular at the beginning. DoD was essentially trying to fulfil the same role that Live Wild or Die! did in the States—a radical anarchist fringe publication trying to ginger things up a bit. When we say that we won, in that the green anarchist perspective went from being the minority to the majority perspective within EF! in the UK over the course of the 1990s, that isn’t quite as arrogant as it sounds... this may have been partly due to our efforts but is probably more due to people’s own experiences of resistance over time. This resulted in lots of people dropping much of the non-violent pacifist ideology, moving more towards an anarchist position and supporting sabotage actions.

—From the EF! postmortem interview circa 2006

This quote is deep. ft holds a lot of history in a few, easily-missed words and refers to a before that is hard so see from the position of one who has only been in the now. There was a time when EF! held at the same time very different ideas of what comprises direct action in defense of the earth. This is outside of debates about peaceful (or not) tactics or what shape a better world should take. This quote refers to a time when EF! (alongside many other social justice groups) wasn’t homogenous. That is no longer true.

On the one hand political people (who describe themselves with terms like anarchist) want to have deep and engaged conversations about the implications of ideas to daily life. On the other this has created a cultural context where participation has entailed a type of conformity.

The example above doesn’t refer to the split between rednecks and hippies but a time when summit protests were being challenged by anarchists as having a limited depth of strategic vision. These same people were developing a tighter connection between a green anarchist perspective and EF! activities. The unforseen consequence of this move has been a further whittling of the kind of opinions, actions, and ideas that EF! participates in. There hasn’t been a rondy in a decade that doesn’t have some sort of identity politics drama attached to it.

Down with the Empire

This essay is a strong conclusion to the DoD project. It does it all: savors the victories, names the defeats, and tells the story of a decade of attempts by human beings to defend the Earth against the rapacious industrial system. It is a thoughtful, considered, un-depressed summation of years and years of thinking and acting.

DwtE frames the history of UK EF! and, like any frame, is perhaps unfair to future ecological actions in the UK theater. It’s a story of birth, land struggle, localism, and ultimately the globalization of the movement. This might be cold solace to those who are still fighting against roads and industrialism in the nooks and valleys of the greater UK. The article implies, “Keep trying but your story has already been told:’ That said, DwtE was a fantastic introduction to the section that followed it, the rare strategic document, or at the very least a solid set of proposals.

The Four Tasks

Somewhere between strategy and tactics is the conversation all of us in the change-the-world movement need to have. At this point I would say that strategy is easy, if silly. It’s easy to declare that peace will be the result of peace, or killing tyrants will make leaders behave. In fact, the focus required to do either enough to test whether the hypotheses work, is in short supply. Grandiose statements-especially since the Internet is so frequently the way we communicate with each other-have become a principle form of non-communication. Tactics is also easy enough. It is simple to talk about the technics, specifics, and experiences of how to deal with meetings, windows, and equipment in the field. But the gap between what we can do and what we want is enormous, it’s existential, and it touches on everything we love and hate about people.

TFT attempts to bridge this strategy-tactics gap and its effort is worth engaging with, even 20 years later, because of how prescient and accurate (if not precise) it was (with regard to the shape of ecological resistance). TFT is, from our perspective, the zenith of DoD.

Growing Counter-Cultures

We need to catalyse living, loving, fighting counter cultures that can sustain rebellion across generations. In both collective struggle and our everyday lives we must try to live our ecological and libertarian principles. Our counter-cultures must be glimmers of ecological anarchy—fertiliser for the growth of collective imagination. Fulfilling this task is what will enable the others to be fulfilled over the long haul. The counter-cultures must be bases from which to carry out ‘thumb in the dam’ actions and give support to rebellions beyond the core. In times of crisis they should act decisively against authoritarian groups. The counter-culture’s eventual aim should be total social transcendence-(r)evolution.

In the US the perspective that counter culture is valuable has fallen entirely out of favor. This is mostly because of the Internet (also somewhat because of the surprising popularity and mis-reading-or at least highly attenuated reading-of “Introduction to Civil War” by Tiqqun). These days in the US there is a disdain for all “things counter cultural. Of course the disdainers were also once the royalty of the same counter cultures they are oh-so-over, but that isn’t the point. The Internet killed counter culture[1], especially what was most visually distinctive about it. For the spectacularized American, that was enough. These days no one is allowed their own special little treehouse in which to foment (r)evolution, not without a thousand blogs of light shining down upon them. And this will not do.

The tension for us, as people who were formed pre-Internet, is that to eschew the counter culture is to embrace mainstream culture: Mom & Dad, jobs and retirement, home ownership and life insurance, kids, dogs, and white picket fences. We claimed counter culture as the escape from that, but mainstream culture has already, mostly, consumed each individual component. You want Mom & Mom, a shared job, no home or insurance, and a cat? Go for it! To put this another way, the problem with American counter culture is that we had no culture in the first place. Since WWII we have had nothing but capitalism’s throbbing successes at solving the problems of human storage and survival. Counter culture, especially as defined by DoD (and by us), is about something else entirely. For starters, it’s about something that spans generation, which we absolutely do not have.

To put this conundrum into slightly more positive language, we feel outside of and opposed to mainstream culture but strongly desire something-like-a-community to fulfill both the spiritual and material needs a culture could provide-so we endure counter culture. We have big dreams for counter culture-which has time and time again disappointed-and believe something connected to our daily life must also be the mechanism by which we participate in the change we’d like to see in the world (which I don’t mind calling (r)evolution even though it sounds dorky to a North American ear).

I think the common criticism of this position is a communist one. We, by whatever broad definition you want to give counter culture, will never be large enough to be a force-to-be-reckoned-with on the stage where a revolution (or even a (r)evolution) would need to be waged. We, to put it gently, are not enough. We aren’t even talking about a Russian Revolution-style change but about survival, fertilizer and safe houses, dance parties and hookups, and even putting thumbs in the dam. It seems hard to fathom a new type of counter culture-mostly comprised of the most educated from the current counter culture that is attempting to build (political) parties, study groups, and gestures towards effects-will have anywhere near the 8keletal structure shown by even the shadow of the previous counter culture.

Forgive us our internal critiques. This first task of TFI still rings true. We need some place where our probable hostility for each other can look and feel much more like conviviality than a civil war. We need this because if there ever were the requirement for the kind of solidarity and unity of action a radical transformation of this world requires, we don’t currently have it. It is possible that the fragmentation of counter culture (a fragmentation that is largely concurrent to the rise of the Internet) is irreversible. That would mean that the corollary to the First Task may be something like reconciling the irreconcilable of a unitary counter culture vs a diverse one that recognized itself and its boundaries, and had an honest self assessment of the accompanying strategic limitation and opportunities.

Putting Our Thumb in the Dam

Just as counter-cultures must open up space for (r)evolution to grow we must also open up time. The life support systems of the earth are under unprecedented attack. Biological meltdown is accelerating. (R) evolution takes decades to mature. Unless force is used on the margins of the global society to protect the most important biological areas we may simply not have enough time. The last tribal examples of anarchy, from whom we can learn a lot, could be wiped out within decades if not militantly defended. Thumb-in-the-Dam struggles aim to protect ecological diversity understanding that this civilisation WILL be terminated, by either the unlikely possibility of global (r)evolution or the certainty of industrial collapse.

This argument is similar to the assertion by EF! types that there is something metaphysical about wildness, therefore justifying its defense at any cost. This kind of argumentation has fallen out of vogue (alongside, thankfully, the deep vs social ecology debate). There are still a thousand not-radical non-profits that are thumbing dams all over the place: saving rhinos. gorillas, rain forests, and other regions and species that will be eliminated as the violence of global capitalism completes its consumption of resources.

An aspect of the radical version of thumbing dams that wasn’t discussed by DoD that is more likely to “open up time “ is green capitalism. Shipping global-north tourists to locations and species in the wild is, perhaps, a more humane and sustainable option to zoos and safaris. The past 20 years has seemed to vindicate this approach more than the one of environmental extremism. Native struggles, which are largely struggles of cultural survival, have been most effective when there are resources under control of natives (whether byways for pipelines or casino revenues) that allow them to get a seat at the table for control of their own destinies. Thumbs in the dam indeed.

The other approach that has some appeal for some radicals (most notably a specific kind of communist) is accelerationism. This perspective is more-or-less the opposite of any kind of ecological concern unless you believe that gaian homeostasis is only possible in the absence of humans. In which case, turning up the heat on human activity, with the resulting crises and collapse, may be the only solution. This is the opposite of putting a thumb in the dam but is one of the interesting propositions since DoD ended.

Preparing for Crises

We must have the ability to defend ourselves, survive, and exploit crises in society including capitalist attempts to destroy us. The divided and industrial nature of today’s society has already determined the instability of tomorrow.

Task Three falls gently from Task One and Two. If we have a place that is something like True Community and we commit to emergency struggles, then we must necessarily prepare for upcoming events. Ecological crises has already been a more salient part of daily life in the past 15 years than in the 50 before it. The only quibble with this Task is that it is necessary but not sufficient to the scale of the crises ahead.

Supporting Rebellion Beyond the Core

The counter culture must act in real solidarity with our struggling sisters and brothers on other islands. Aid them in whatever we can and bring the majority world battlefronts to the boardrooms, bedrooms, and barracks of the bourgeoisie.

Once you have a real fighting force, one committed to doing something meaningful in the world. then of course the list of what you have to do, what different pressure groups will try to get you to do, can get quite long. The main criticism we would make of the Four Tasks is that they bury thousands of tasks in the four. What is an engaging and critically important conversation about “What is to be Done?” is mostly a series of four principles with little to direct a reader. It is largely a list that details the dozens of complicated projects that could be embraced given infinite time and energy.

The challenge of Task Four (which is basically to help others) is the challenge of environmental activism (actually, all activism): how do we help people who are outside of our experience in real material, cultural, and spiritual ways. The usual answer is that our actions should be directed by solidarity and not charity but this distinction is nearly impossible to define and, in practice, hard lo find examples for. This is not to say that charity is de facto bad but hoping and wishing an action isn’t charity evades an important principle, which is that the people who have money, resources, and power get to decide who they shower those things upon. not need, value, or the people who actually receive the largesse. This privilege is mostly discussed as a type of crime committed by those who have it which seems to have resulted in less and less generosity from rich people.[2]

At the heart of Task Four is an imperative. We must aid our brothers and sisters. This may be the case if we assume some brutal categorizations. “Brothers and sisters on other islands “ seems synonymous with “the poor and huddled masses” of the world. Bringing their fights to the bourgeoisie is a type of restatement of the classic Marxist hagiography with, perhaps, a humanist twist. If we thought categorization of the Marxist variety were a solution to ecological devastation why wouldn’t we be Marxists? Do we really think that bringing new data to the boardrooms and bedrooms would change them one iota? Perhaps what I was hoping for from this Fourth Task was a new model of revolution, a social change movement that was different, but it seemed there wasn’t nearly the imagination about how to do things differently as there was about how many things there are to do.

We’ve drifted again towards having a critical analysis of The Four Tasks but that is only because this nearly 20-year old document is still entirely relevant to the form and function of radical activity today. Almost none of this document feels dated. Today there would be sections on Global Wanning and Intersectionality but fundamentally this text is still a relevant starting point for any group attempting to answer the questions herein. This is an incredible feat and for that I’d place it at the head of the pack of articles that attempt a similar feat-but much more modestly-like Desert, “Earth First Means Social War,:’ “The Issues are not the Issue;’ “You Make Plans—We Make History;’ and various pieces by the Green Anarchy Collective.

But What If It is Too Late?

If you will indulge us for a few minutes we’d feel remiss if we didn’t mention a topic that DoD didn’t emphasize. What if we are too late? This question of “lateness” has a material, cultural, and metaphysical component that we will address. There were people in the eco-scene that were asserting something along the lines of this question but they made the mistake of confusing means and ends and as a result blamed the first victims of our lateness rather than keeping the conversation abstract. Abstraction has the benefit of not summoning emotions, of seeming to be removed from a particular interest group or daily life, which allows us, strangers, to discuss something big and profound. It is an abstraction to say that the world is going to end and there is no hope of redemption (just as saying the opposite is also an abstract ion). But of course endings will impact a great deal of people and are incredibly dramatic and even cataclysmic. For the sake of talking to strangers and talking about something impossibly difficult, for the rest of this section let us ride the line between abstraction and something real.

It is very much in the ecological tradition to abandon hope: in human agency, in our capacity to slow the gears of Empire’s machinery, that we could make a difference on any stage we’d think worth our energy. This tradition tends to argue for a return to nature, for a withdrawal from the affairs of man (or civilization or society), or towards a spiritual life. Of course there is no escape but there is a principle that is at odds with the Four Tasks and doesn’t require its fundamental hope. What if instead of building a counter culture that doesn’t appear possible-in order to effect a holding action to the decay of this civilization, to prepare for crises, and to (poorly) support the actions of others around the world who are doing the same—what if instead of all that, we just live our lives. What if we accept that we are just a few human creatures among billions?

Instead of becoming activists, or politicians with no constituency, we do something else. We don’t try to run and hide (as if that were possible), but instead live as a native to our habitats, do something horrific to bourgeoisie society, live quietly, outside of the organizational model of the Christian sects. Let people be and live on the land, perhaps wildly, perhaps in all the countercultural glory you possess.

If it is too late to, save humanity from itself then it may be time to wrap up our affairs. In that cause, a more nihilistic ecological perspective has a few modem faces that make sense to mention as a way of concluding. Two of them are publishing projects, inheritors of the DoD legacy but perhaps, in addition to The Four Tasks, also participants in a Fifth Task. Dark Mountain, a publishing project from the UK, is comprised of dozens of authors, many of whom participated in the anti-road activities of the 90. They are best summed up by this, The machine is stuttering and the engineers are in panic. They are wondering if perhaps they do not understand it as well as they imagined. They are wondering whether they are controlling it at all or whether, perhaps, it is controlling them (Dark Mountain Manifesto).

The second project, in which the editors of this book have some involvement, is Black Seed. a newsprint project somewhere in the intersection of indigeneity, green anarchism, and direct action. And the third, non-publication project is the actions of eco-extremists, especially in Mexico, like Individuals Tending Towards the Wild, or Wild Reaction, tendencies that attempt to treat human life as if it is not. in fact. at the center of creation. The influence of The Four Tasks weighs heavily on all these projects.

Conclusion

While we have spent most of our energy here focusing on the impressive and influential conclusionary documents “Down with the Empire, Up with the Spring” and “The Four Tasks;’ we intended only to highlight what was great about DoD. By maintaining some semblance of an editorial line, a set of high-quality production efforts, and a theoretical axis around a broad green anarchist perspective. it has maintained its position as one of the most important radical green publications ever. We found the lack of memory of this great publication to be offensive and put forward this book take to remedy that situation.

We hope in the following four hundred plus pages you will find agreement with us as well as your own uses for the great material of Do or Die: Voices from the Ecological Resistance.

Environment

The Day They Drove Twyford Down! (from issue 1)

The battle for Twyford Down

For those who don’t already know, Twyford Down is an area of outstanding natural beauty just east of Winchester in Hampshire. With that designation, numerous S.S.S.I.s [Sites of Special Scientific Interest] including the water meadows lining the Itchen valley south of the Down, and two significant scheduled Ancient monuments-an Iron Age Village and a bunch of medieval tracks-the Dongas. Twyford is also one of the last known habitats of the Chalk Blue butterfly and six different species of orchid. It was supposed to be one of the most protected natural sites in England. Indeed, it was placed in the trust of Winchester College by two old boys that bought it in the 1920s to preserve it from the city’s urban sprawl.

The year’s actions to protect the Dongas have been well covered. Since February 2, many blockades and occupations of the work site have taken place, but still the Department of Transport [DoT] carried on regardless, determined to build their precious motorway. During the summer a camp was set up on the Dongas, where activists planned and based actions against the work site on the water meadows, which by then was being raped by the contractors. By the Autumn the contractors were looking towards the Dongas to begin their motorway monster. This is when the most oppressive and intimidating , tactics against the campaign took place.

The Dongas Tribe declared the site an autonomous zone in September, and began building fortifications to defend their land. Tarmac [a British building materials company] had now got the contract to go forth with the cutting, and at this point a virtual siege began with paid security guards having their lookouts next to the Dongas.

The siege effectively ended on the 29th of October after sheer incompetence on the legal front. The previous Monday, (26th of October), the DoT successfully pressured the Estates Bursar of Winchester College into applying to the local court to evict the Dongas Tribe. The summons was so ill-made that that when presented to court that Thursday, the judge ordered the case adjourned until 9th of December, well-past the end of the Cooper Lyons contract. With the tribe securely in place and no police cover, all the contractors could do was finish work on the Water Meadow and cut their losses.

The main contract begins

Tarmac spent well after midnight on the 1st of November moving into their depot in Compton, two miles south of the Down. The next morning forty contractors started work on four different sites along the south side of the Itchen Valley, the Tribe were desperately outnumbered and somewhat intimidated. This was compounded by the fact that one of the security guards was suspected of an Arson attack against the Tipi watch post in the trench field a couple of nights after Tarmac arrived. It took until 4th of November for EF! to react nationally. Sixty EF!ers marched across the Itchen Valley and stopped the work on all four sites, freaking out Roger Jackson so much that that he lost control of his car and parked it half way up a bank for the rest of the day.

The Dongas tribe continued to obstruct work on the North End site until around the 30th of November. On this day, a Tarmac foreman frustrated by continuous disruption charged demonstrators with a JCB and one of the workers threatened a second arson attack on the camp. The cambers took this second threat seriously and demanded that no further action be taken against the contractors. The Tribe member that came closest to injury in the first attack was outraged at this decision and walked out of the camp, saying that by allowing themselves to be intimidated, the Tribe had made themselves hostages of the good behavior of others opposing the destruction of the down. The camp had vetoed ecotage around the area of the camp for months for fear of retaliation-by vetoing all action, the original reason for the establishment of the camp had been lost the day when Winchester college’s summons was to be heard, the DoT felt that they were in a strong enough position to invade the Dongas. Due to the lack of co-operation from Hampshire Constabulary from the 27th of October, the home office recommended Tarmac hire Group Four for the invasion instead.

At dawn, a bulldozer spearheaded the assault, followed up by one hundred Group Four thugs and all the workers at Twyford. Although the tribe had been supplied with a mobile phone to call for support, it had broken down and had not been repaired in the malaise preceding that day’s events. Despite the paucity of communications, over fifty EF!ers had turned up by noon. The contractors put up a barbed wire compound around DoT land and started to remove turf within, but the tribe weren’t taking this without a fight. Their attempts to invade the compound in the next two days were met by violence that hospitalised four of the demonstrators. To control the situation, a hundred cops were drafted in and they in turn made arrests when EF!ers attempted to stop the destruction of the woods at the bottom of the Dongas by occupying trees and the contractors vehicles bulldozing them down on Friday 11th of December, despite this unbelievably wanton destruction on the side of Tarmac, the tree-sitters saved a small stand of sycamores and this became their camp site as the tribe began clearing off Winchester College’s land ready for the 14th December evictions.

On the Wednesday, Hampshire County Council objected to Tarmac’s spurious claims that the two footpaths across the Dongas had been diverted. The 13th of December was an unlucky day for the contractors. Armed with cuttings from the local paper about the destruction of the paths, fifty members of the Ramblers Association turned up at the Down and insisted on the right to walk one of the original tracks. Joined by the tribe and their supporters, the ramblers laid siege to the compound. After ripping the compound gate off its hinges, they barged through fifty Group 4 guards that had linked arms across the breach, and proceeded to walk to the far side of the compound before the cops arrived to “restore order:’ Those biffed out of the compound are now taking the obstruction to court to rip it wide open.

A tribe member describes Yellow Wednesday!

At the battle of the Dongas we witnesses the lengths to which other human beings were prepared to go-to enable destruction of nature to continue.

We saw outnumbered protesters being assaulted, then arrested for assault. Activists sustained injuries that the police surgeon described as evidence of systematic beatings. When several arrests failed to enable machinery onto the Dongas-arrests were forgotten as a tactic, and were replaced by brute force and scare tactics by 70 men in yellow jackets.

As the Earth defenders persistence in the face of arm twisting, head-butting, pressure pointing... etc, became evident 50 black hats waded in.

Instead of making arrests they took over the administration of violence. Two courageous earth sisters were rendered unconscious by wind pipe constriction and suffered torn neck and shoulder ligaments-one being kept in hospital for observation. Many others visited casualty, with barbed-wire cuts, bruises, muscle strain, and abrasions, charges are being brought.

Despite these tactics and heavy outnumbering the tribe succeeded in keeping machinery out of the enclosed area of the Dongas-From dawn until dusk, throwing their all into the blockade, oblivious to personal injury, risking their lives in one final effort to protect that beautiful piece of land, as if the very planet depended on it!

Dawn the next day saw 19 people who were left fit for the protest and 100 black-hats joining the yellow jackets. After attempts at a gate blockade were repelled by a wall of black-hats, physically and mentally numbed protesters wandered around the perimeter fence, watching the surreal massacre that followed. It was like watching a strange dream, by midday all the trees and scrub had been bulldozed, and the unturfed part of the ancient track-ways had been reduced to a huge field of chalk.

The only obstruction left was three trees, in the middle of the site occupied by the “never say die” tree sitting club. Huge clouds of smoke billowed over the site from the burning pile of murdered trees, as the bulldozers continued their work. The battle was lost...there were a lot of sad moments but our spirit was not broken. We gained insight and an overwhelming sense of unity. We also saw that other human beings were willing to go to any lengths to achieve their destructive aims...we must be strong ...we must stand together... the Tribe lives on! The Dongas are dead! Long live the Dongas Tribe!

What now?

Many, particularly the media, who like a nice, neat story. will see the move on the Dongas Camp as the closing act of the Twyford drama. They do not understand how precarious Tarmac’ s current position is. Prior to starting the Twyford contract, Tarmac lost millions when a contract collapsed in Swindon. That on top the general damage the recession has done them, forced Tarmac to beg for a £30 million hand out from the government. They have put in a £24 million bid for the Twyford contract, a third below its proper value, meaning any delay will push them into penalty clauses. The intervention of activists aside, there will certainly be such delays. They will have to cut chalk through Winter and attempt road building across the bottom of the Itchen Valley, which used to be a complex of water meadows meaning they are prone to turn into quagmires. This contract is set to run for two years and the political rationale for it-building infrastructure for European economic union-is looking more tenuous by the day as the Major administration wastes away. The battle for Twyford has not ended-it’s beginning. With proper organisation and determination we can win this crunch battle with the road lobby. The implications of this victory will carry far beyond a small corner of Hampshire.

The events of 4th November show that we can stop work across Twyford using traditional tactics, given the numbers. If they think they can stop us with threats and violence, we’ve got to make damn sure they don’t. Hunt Sabs regularly get hassle but carry on regardless-learn from their example. They don’t hesitate to document violence against them and bring prosecution.

Obstruction on site needs to be coordinated and supported. The number of days’ work lost is what counts in defeating Tarmac. Consequently, it’s better we have a sixty-strong demonstration two days a week than one demonstration twice that size-that’s overkill. Those on site should make sure that they take down full details of works ongoing and subcontractors involved.

Consideration should also be given to those groups too far from Twyford shouldn’t be confined to the Home Counties. To broaden it out nationally, every Tarmac and associated subcontractors office, depots and sites in the country should be targeted, (A list can be obtained from South Downs EF!). As subcontractors addresses become known, they should join the hit list, not least because they are more vulnerable to persuasion than the larger companies raping the down. Those that can’t make it to Twyford on their day of the week must hit their local target instead. Solidarity actions are already ongoing against the DoT in London and ARC (who supply stone to Tarmac for Twyford) at Whatley Quarry in Somerset. Additional action against the Dean of Bristol University who also happens to run Winchester College are already in the pipeline.

Its urgent that people explore whether Tarmac or any other subcontractors use freepost addresses or freephone numbers—armchair activists across the country can cost them thousands, legally and from the comfort of their own homes. The possibility of phone, fax and telex blockades should also be explored.

There is another string to our bow, too. Tarmac have shown by their behavior on the 9th December that they don’t care for the law and only understand money. Well, we can. beat them at their own game on that one, cant we! There is no point in fighting with one arm tied behind our back. After all, Earth First! only respects natural laws. Every leaflet you produce could contain the information needed for a cell to wreak £10,000s of havoc against the contractors and even put smaller subcontractors out of business. If you feel so inspired, study eco-defense and the A.L.F. publications doing the rounds so you know how to do it what it takes. As every channel for negotiation now seems closed, ultimately the only way Tarmac are going to be stopped is by being destroyed.

No Compromise in Defense of Planet Earth!

Trees for Life: The Amazon on our Doorstep (from issue 2)

Earlier this year, some EF!ers went to see Alan Watson at Trees for Life [TfL] in Scotland. He says:

Deforestation and loss of biological diversity are now global phenomena, and I believe it is vital for the world to have positive examples showing how the return of natural forests can help heal degraded lands... Trees for Life has been working since 1987 to restore the Caledonian forest in the Highlands of Scotland... one of the most biologically impoverished parts of the world, where only one percent of the original forest remains.

Scotland is in the position now that the Amazon will be in in less than 100 years time (unless EF! and others can make a difference). The industrial system that was born in the British Isles began by razing its own environment to the ground, then moved further afield, poisoning the Americas, Asia, Africa, and so on. This is one of the beauties of the TfL project-it sets a global precedent for wilderness restoration and the rejection of civilisation, in the very place where industrialism originated.

Alan Watson has a strong commitment to the idea of wilderness. As an article in the Independent newspaper stated: his scheme has no room for ‘sustainable’ woodland, worked and marketed for timber. When he says he wants a natural wilderness he means exactly that. No exploitation, just woods. This is just the kind of vision we need in the badly-degraded and tamed British landscape, and with the return of the wildwood, the malignant, oppressive influence of modern-day society will progressively ebb away.

EF! in the U.S. has a slogan: As wolves die, so does freedom. The last wolf on these islands was killed in 1743. We have forgotten the meaning of freedom. With projects such as TfL we have a chance to remember.

Watson’s plan is truly vast in scale; he is targetting a 600-square mile area of largely bare, roadless hills in the North Central highlands, which happens to contain three of the best surviving forest remnants. Using these remnants as a nucleus, his ultimate aim is to reafforest 150,000 hectares, and when possible, to reintroduce the large mammal species that previously inhabited the area. This means that we could be seeing brother beaver, sister bear, wolf, lynx, and bison, return to these shores before long, thanks to the efforts of TfL and others. There is already talk of establishing a wolf pack on the Isle of Rhum, off the Western Coast of Scotland.

This is another important symbolic move-experts reckon that most of the large mammals with whom we share the planet will have been rendered extinct shortly into the next century. To reintroduce species shows that this trend is not inevitable or irresistible.

TfL are keen on the idea of earth repair work. An apparently irreversibly-damaged piece of land can be brought back from the brink. This shows that humanity can co-operate with nature instead of trying to dominate it, and that “nature bats last.” No matter how hard the power junkies and business-beasts try, nature (meaning ordinary humans as well as other species) will ultimately overwhelm them, and their tarmac.

EF! needs to widen what is at present a very narrow definition of direct action. One member of the TfL work party describes his experiences as follows,

my week in Glen Affric was wonderful because it made me realise that Las an individual, could do something constructive to help heal our Earth. Not only could I do something, but that it was only through the efforts of everyone that changes happen.

He took these lessons and applied them to other areas of his life. As a graphic designer, when asked to design a report for a temperate forest-destroying pulpmill in BC, he at first refused, and later resigned his job. His experiences can be summed up in that buzzword, “empowerment;’ a feeling familiar to many EF!ers. What TfL are doing is as much direct action as blockading an ICI plant or a bulldozer at Twyford Down. We need to recognise that we can help to actively heal the earth, as well as carrying out the essential work of stopping business and governments from wounding it further.

What Can I Do?

We were amazed at the scale of destruction in the areas we looked at. We are all used to the idea of far-away places being ravaged deserts, but here is something on our own doorsteps that needs to be done. No more buying newsletters about death and destruction, here’s some people doing direct action right here, and they need help. There are a series of nine work weeks in Glen Affric between March and June this year. Glen Affric is still a beautiful place to be, and if you can leave it better than you found it, then this could be a real example of that much abused non-word, eco-tourism. The work involves planting native Scots pine and other related tasks. If you can’t make the time for this, you could support them by becoming a member, finding out more (so you can tell other people), and perhaps doing some fundraising.

There are many similarities between EF!‘s outlook and that of Trees for Life. We thus urge all EF!ers to support them. You, as well as the Caledonian forest, will be the richer for it.

They can be contacted at http://treesforlife.org.uk/

If you would like to do something about the rest of this devastated isle, please contact SDEF! ...Perhaps we can get something started.

—Noddy, MA

A Letter from Scotland (from issue 3)

For those who are ‘ aware of the real history of Scotland, the consequences of the actions taken by the colonial administrators on the Scots are self evident. Individuals took advantage of the shattering of customary law to accrue power and influence for themselves at the expense of their own communities collective ownership and security. Traditions stood in the way of profits, so traditions were disregarded. Culture stood in the way of market extension because culture usually involved community ties, solidarity and reciprocity. The wholesale eviction of the indigenous population was then carried out with a blind economic totality and is still a matter touching our inner-most feelings. In this rough and ready article emphasis has been placed on the redefining of land as private property and then its transfer to an elite leading to the mass removal of whole communities for financial gain in a process which is alive today.

The phasing out of Scotland’s culture was top priority as it offered a real challenge in the form of a viable, self-reliant and alternative way of life which wasn’t massively wealthy, but did tend to protect the poor and regulate injustice. The elimination of the native systems, justified by perpetrators and apologists as improvements has been ignored by the education departments, whose task it is to condition a labour force of ignorant and eager consumers.

Private property has been legitimised through the imposition of Anglo law via the Scottish office. The poll tax and more recently the water privatisation issue serve to reveal the imposed structure of colonialism clearly.

The Scottish office play a leading role in the undermining of real democracy in Scotland but they are not alone. The powerful corporate bureaucracy of Strathclyde regional council along with the rest of the regions have shown no resistance to the imposition of poll tax. Instead they took on board the unpopular tax in co-operation with the Tories and have used all the powers at their disposal to enforce it, showing that they have virtually transferred their allegiance to the colonial regime. Strathclyde region have already been caught out buying water shares south of the border and meeting with prospective developers.

The people of Scotland are landless as a result of historic coercion into the capitalist labour force. Glasgow, historically a slave camp of the industrial era, doubling as a reservation for the dispossessed natives has been assimilated into the British capitalist system. For this relatively new economic order to be adopted by people, firstly their communal systems of land tenure had to be broken up to substitute with private ownership. Assimilation is ongoing and capitalist ideals are enshrined within schools and institutions for that purpose. Accounts of real history are smothered as a calculated act of policy. Defunct economic theory replaces free thought and the mercenary ideology continues to usurp native intelligence and morality.

The cost of this deception is very high and only those who are prepared to DoDge their social/cultural integrity find themselves wealthy enough to insulate themselves from the crisis they are helping to create, be they aware of it or not. While a self-destructive and sociopathic business elite remain in the cockpit of the planet, locked into a suicidal doctrine of economic growth at all costs, our future will remain in the balance. Degradation of people and the environment is the price that must be paid on this path.

Yesterday the Caledonian forests fell to the speculators from the south, today from Amazonia to the Siberian forests, the seemingly unstoppable encroachment of market forces continues to wreak environmental havoc. Beyond third world debt and economic destruction and the sharpening division between rich and poor, the market logic now threatens the fundamental biological diversity on which life itself depends.

We now live in a world where we are acted upon globally, where decisions affecting our lives are made at levels so far removed from ordinary democratic practices that no citizen has a hope of influencing them. The power of transnational corporations (TNCs) and multinationals cannot be ignored.

-

703 of world trade is now controlled by just 500 corporations, which also control 803 of foreign investment.

-

Shell Oil’s 1990 gross income ($132 billion) was more than the total GNP of Tanzania, Ethiopia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Zaire, Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, and Pakistan combined. 500 million people inhabit these countries—nearly a tenth of the worlds human population.

-

Cargill, the Canadian grain giant, alone controls 603 of the world trade in cereals.

-

Just 13 corporations supply 803 of all cars; five of them sell half of all vehicles manufactured each year.

US corporations spend more than one million dollars annually on advertising. The average US citizen views 21,000 TV commercials a year. Control of the collective consciousness plays a vitally important role for the success of big business.

These corporations are the dominant force in our world. Disembodied from any one culture and any one environment, they owe no loyalty to any community, any government, or any people anywhere on Earth. These institutions, from the military to government departments and international agencies are driven by a desire to promote their own interests, to perpetuate themselves and increase their power and influence. Decisions are made not because they benefit the community or on environmental grounds but because they serve the institutions’ particular vested interest.

Employees are similarly disembodied from the real world. When acting for the organisation, company loyalty takes priority over moral and cultural restraints that mediate the rest of their lives. The power wielded by these organisations is greater than that of many, if not all, governments and makes a mockery of certain countries claim to democracy. On the far flung frontiers of the developing world, governments and multinationals are forcing resettlement schemes pushing indigenous peoples off traditional lands, often backed up by the military as part of their assimilation policy, which aims to civilise tribal peoples. This development process frequently begins with widespread brutality and extermination and ends with forest lands being systematically destroyed and plundered for their natural resources.

It’s probably fair to say most people are finding it difficult to make sense of the increasingly complex situation we are in. Many don’t give a damn and the present government—apart from a catalog of major disasters—generally reflects the desires of an ever more materialist society. Most people are busy fighting for a fairer slice of the capitalist cake and don’t have much objection to the system itself but only to the way the cake is sliced. The socialists are telling rights. A fragment of non-feudal land on which we have traditionally known and cherished liberty.

Both socialism and capitalism are concerned with exploiting this planet and so cannot be supported by anyone who wishes to preserve the various ecosystems that make up our home. Socialism is an understandable reaction to a brutally unfair distribution of wealth but it is not enough—we must help recreate a system based on needs not greed.

For Scotland to go forward into a genuinely enlightened future we must prepare the ground by illuminating the present in the light of the past, ending the cultural curfew. These sentiments are not racist but pro-culture, based upon the principle that we can’t fully understand or appreciate other cultures if we don’t understand or appreciate our own. Real possibilities for positive change will take place if we shrug off our colonial status, breaking the chains of a system that has fatally undermined our local institutions and cultural patterns, which previously prevented one set of private interests within our society from monopolizing power and imposing its will on the community. We must shut the back door that has been opened to personal gain at the expense of the community’s security, both social and environmental.

The challenge remains for local people to reclaim the political process and to reroot it back in the local community. For people to have inadequate information about their past and little means of acquiring it is a tragedy. It’s vital that we fill in the information gap with an account of real history from our own uniquely Scottish perspective as opposed to the imperial chauvinism which usually passes as such.

Car Chases, Sabotage, and Arthur Dent (From issue 3)

Twyford Diary — Part 2

Twyford Down has become a symbol of resistance, a training ground, a life changer, and a kick up the arse to the British green movement! Below is a brief chronology of events at Twyford since 22 March. The reports of actions dating from mid-February to March 22nd can be found in The Twyford Diary Part One—DoD Issue 2. To avoid security fuck ups mentions of monkeywrenching will be limited to quotes from DoT affidavits. Action at Twyford may seem hectic but what I cannot put to text was one of the greatest things to come out of Twyford. That is the camp, the community.

The last diary finished off on March 20th with the Arch Druid of Wessex cursing companies at Twyford. This is a transcript of the conversion he had with Mr. Chapman, the Mott MacDonald officer, it is taken from DoT evidence in the Twyford 76 High Court case.

Druid—I will give you my title. This is an official message from the Arch Druid of Wessex, also a Bard of St. Catherine. This site has been declared officially a sacred site... We would like to inform you ... that we have issued a curse against your company. This curse is not a curse against your workers; none of your workers need fear anything personal against them. It is not a death curse but your company will find it will lose money, your workers will lose their jobs, your equipment up here will start breaking down, and you will find this enterprise up here is a white elephant and this thing will not finish until you leave the landscape alone.

Mr. Chapman— wait a minute, we understand—I just want to make it clear whose authority has put this.

Druid—This authority is from the Order of St. Catherine who are responsible for the site up there. St. Catherines Hill and the environment around.

Mr. Chapman—Responsible for—and who declared this on the site as well then?

Druid—This is declared by the Council of British Druid Orders which contains all the Druid Orders of the country including Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Manx, Brittany, and suchlike!

promise, you will find every one of you will be out of a job. Over the next few months these words were in many ways to become true, as protest activity increased and equipment started breaking down.

22nd March

17 protesters hightailed it around the site causing much havoc, no work is done due to the combined effect of protester intervention and Mother Earth pouring fourth buckets.

23rd March

Ten people as above.

24th March

According to a DoT affidavit, “There was fairly substantial vandalism to Hockley bridge overnight”. 22 people including a number of Nicaraguan activists, split into three groups and ran all over the site, DoDging flying tackles from group 4. It was a half day and we caused a total of seventy five minutes down time.

25th March

It rained, no site work done.

26th March

We arrived 26 strong at 7:45am. How we managed to get up this early, god only knows! We succeeded in occupying one of the large excavators. Two group 4 men pushed an activist off the top of the digger arm 25 foot up, this resulted in a number of chipped ribs. After three attempts six protesters succeeded in stopping a smaller mechanical monster. The Hockley road was then blocked by a sympathetic driver while demonstrators swarmed onto the stranded digger caught in the middle of the road. Up the hill comes an assortment of vans and landies containing over 50 of our local constabulary. Hopelessly outnumbered and standing in a sea of black hats, most demonstrators leave the digger with two people locked to the arm. Two people are arrested on the small digger and by midday the remaining locked-on activists have been cut off by hydraulic bolt croppers. We then went down to what was the Dongas site and blockaded the entrance causing a tail back of three dumper trucks. Group 4 eventually got their act together and pulled us off the road. The actual loss of production was four hours (DoT affidavit). Police later arrested two demonstrators for Criminal Damage to batter rails-charges were not pressed.

March 27

Thirty of us once again spent the morning from 7:15 onwards stopping this and blockading that. As well as group 4 we were once again confronted with thirty police officers. Our numbers were a third of the opposition and due to this we were not as effective as the day before. During the protests there were six arrests including the co-editor of The Ecologist magazine. Five out of the six in the nick went on hunger strike. This lasted until after the court case three days later.

March 29

Ten minutes after midnight two people are caught by group 4 amongst the machines in the cutting. When the police arrived they found another two others hiding. None were equipped to cause criminal damage so they were released with cautions. The court case of the six arrested on the 27th resulted in them all getting unconditional bail However one defendant was done for contempt of court—e.g. he punctuated the Tarmac laccies sentences with bleats.

April 3

Twenty-three of us arrived on the site at 7 am, after stopping the work for a short while and after various hair raising events including the tipping of a dumper trucks full load of chalk onto an activists head, group 4 managed to get us off the site. A number of people then started to Dance through an area of wet concrete which had just been laid. This happened several times until a contractor kicked down one dancer and while two held him down, tried to hit him over the head with a spade. Luckily the demonstrator came off with a fair amount of bumps and bruises and nothing worse. On this action as on others a number of female activists were groped and had some articles of their clothing pulled off. This led to group 4 being nicknamed grope 4 and a recommendation that considering the violence of contractors, security, and police towards specifically female activists, we should not go onto the site in women only groups, or in groups under twenty.

A number of group 4, we are unaware of the figure, had by this time been injured. Injuries ranged from sprained knees, from slipping while trying to rugby tackle us. to more serious fractures. Whenever we tried to occupy a digger the drivers spun the shovels like psychopaths, none of us were hit but group 4 were not so lucky. Tarmac and the police have often cited these incidents to back up the idea that Twyford Activists are a violent mob. This is not true, we are not in any way responsible for the accidental injuries and deaths of DoT employees. It simply shows the idiocy of some security guards and the danger of putting macho men in charge of very big hunks of moving metal.

We sauntered home, rather disempowered. As we left the site the police arrived in force. immediately arrested three people for breach of bail conditions. At this time the courts were often giving out outrageous bail restrictions saying we couldn’t go within an exclusion zone three miles long. This included the railway, the A33, and large parts of Winchester itself. They even banned us from going to St. Catherine’s Hill. Of course we were still observed on site and figures were often seen in the trees of St. Catherine’s.

April 4–16

For much of this period the sky opened up and our feet got muddy. This made the contractors’ work impossible and once again Mother Earth did our job for us. For various reasons our numbers lowered, however the situation soon changed...

April 17

An overwhelming day of action attended by over 250 people, led into the cutting by David Gee (Ex-director of FoE). Media reports concerning rampaging mobs and security guards receiving fractured skulls were very imaginative and came originally from surprise, surprise the police. However back on the real world the consultative engineers in court evidence said Two group four men received minor injuries in the scuffle. Another DoT affidavit goes on to say:

The protesters came to the top of the hill arriving on site just north of Arethusa clump Almost immediately 50 or so protesters rushed the line of group 4 guards who fell back to the position of the nearest machine. Another machine was overrun by protesters almost straight away. Group 4 fell back to the second machine in an attempt to keep it working. The protesters actions were very vigorous and within a short time (three minutes) one protester got onto the machines boom and this stopped work.

No work was done in the cutting all that day and: There was considerable damage done to machinery all taking place during the protest. Tarmac claim that about a dozen machines were “seriously” damaged, some written off while others remained inoperative till May. Needless to say no one or nothing was caught.

April 19

About 10 of us occupied the Mott MacDonald office in Winchester. This and the previous raid/occupation, (see “Twyford Diary, part 1,” page 1) was not only useful in that it disrupted work, but also in that it brought to light just how DoDgy they are. From obtained documentation we found that not satisfied with being one of the most hated Consultative engineers in Britain, they are also involved in building a logging road through the Venezuelan Rainforest, urban redevelopment in Jakarta (knocking down slum dwellings!), the horrendous World Bank Bangladeshi Flood Action Plan and they are even building a bypass around Bagdad!. Well, I think we can truly say BASTARDS! One minor was arrested for breach of the peace, e.g. being locked onto a radiator and singing, but was released six hours later with no charge.

April 20

We attended the opening of the nearby controversial M36 Salisbury Bypass Inquiry. One activist being infuriated with the actions of the Inspector did a sit in with his coat over his head to the chorus of Jam being muffled, much to the outrage of the inspector who closed the inquiry for the day.

April 21 Second day of the Salisbury inquiry

Outside the hall where the Inquiry was being held was a riot van and a police landie. Inside a collection of sturdy Security men were making their presence known. Three of us were removed by police while trying to ensure a democratic Inquiry. Our actions, in the end, secured the production of written & audio transcripts of the proceedings, an objectors office, a creche, and evening sessions.

April 22–23

It rained and rained and rained, I love the rain!

April 24

Environment Day at Winchester Cathedral. The protest camp set up stall. A large banner was hung saying “Has the environment had its day?” on scaffolding outside the cathedral, and some happy Twyford campers were subsequently chased around the grounds by Cathedral vergers.

April 28

Meeting with Ecover to discuss boycott

April 29

The request by the Department of Tarmac for an order to Injunct the Twyford 76 was adjourned as the judge ruled that the governments “case evidence was inadequate”. Much jigging outside the high court.

April 30

Beltain gathering of the tribes. 2–300 came to stay for the weekend. The gathering lasted all weekend, and was the first, (and unfortunately one of the only) free festies of the year. The greenwood was once again awoken.

May 1

Work was stopped on three sites by 150 people. According to a DoT affidavit:

At 8.45 hrs a group of protesters raided one of the small earth-moving operations at Shawford Down and did some very severe damage to the excavator before making off There were between 35–50 of them and they seemed to know exactly what to do to cause the most damage to the machine. At the time much of the detailed setting out of the structure in the area of the site was destroyed.

The graffiti on the digger indicated that it was one of the cat 245’s only just back in service after the April 17. The driver of this digger the next week jacked in his job and moved to the Skye Bridge contract in an effort to escape “eco maniacs.” Bad location for an escape!

At 10:20 another group of protesters were at the top of the down and they then started to invade the site as they usually do until...the Blackwells foreman decided to park up the machines to prevent damage...There were many scuffles with protesters in the intervening time where they succeeded in partially stopping several machines...At 10:25 another group of 40–50 protesters went to the Bar End Bridge and succeeded in stopping all works for an hour or so until they started to walk up to join the other group on the top of Twyford Down. There were two machines damaged adjacent to the Bridge: a bulldozer and a grader.

On the way to meet action group 2 we spotted dumper trucks whizzing here and there, and after a few minutes we managed to stop them. Then without warning one of the drivers revved up his engine and drove straight into a group of protesters, most jumped out of the way but two held their ground. Alex from Aire Valley EF! (Leeds), was knocked over by 17 tons of dumper truck and for 10 minutes or so had one of its tires on his chest, for a while we thought he was a gonna. An ambulance came & took him to hospital, amazingly he only sustained a sprained shoulder! Guess who’s got the goddess on his side! He is pressing charges so if you were there, contact Aire Valley EF! NOW.

May 2

The festival of Fire—Another great day of celebration. It was however marred slightly by a couple of hundred police evicting the techno rave in the adjacent field. A very violent situation was narrowly avoided. The ravers after two days of dancing didn’t have the energy to resist, so many a riot shield wielding policeman didn’t get the fight they were so obviously looking forward too.

May 3

This day turned out to be another bizarre one. Overnight two people had been arrested for criminal damage, for allegedly cutting down the fencing around the cutting. One of the activists was badly roughed up by group 4 while waiting for the police. The sun came up and the action began. We didn’t need to take action against the main site at Olivers Battery as the ravers were still using the site as a carpark. Eager not to be out-staged two groups hit the cutting while a third allegedly hit the Compton site. In the words of yet another DoT affidavit, (staked they now reach a foot and a half):

9.30 hrs the first group were now moving up plague pits valley...Blackwells decided to suspend operations and move all plant at the top of the site down to the Hockley traffic lights, where they felt Group 4 could contain the trouble more easily. Unfortunately the protesters were too quick and succeeded in stopping one of the excavators...and preventing another from coming across...A second group of forty came onto the site and started to create problems. 10.00 hrs. The three large motor scrapers were parked up and the protesters tried to rush the larger excavators and there was a serious incident, when one Group 4 man was hit hard in the back by one of the excavators ...He collided with another Group 4 man who was also injured.

Howie who the police are busy framing with an assault charge on a site he wasn’t even at: on April 17, was seen on the demonstration (a breach of his bail conditions), and, two constables gave chase but he eluded them. A car chase around the South of Hampshire then commenced. We believe the Tarmac Site Supervisor broke speed restrictions on numerous occasions! Tut tut. Howie however once again eluded them, Hurrah!

At 10.40 hrs the machines were parked up and left. At 11.00 hrs there were reports of damage to machinery at Compton by a group of people in 8 cars who stormed the area of the site when no work was in progress. They did a severe amount of damage to a medium excavator and to another medium excavator, a large road roller, a track shovel, and compacting plate. A large amount of setting out detail was also destroyed. Shortly after the time these incidence are alleged to have happened those who just happened to have been there were confronted by a horrific site. A quarter of a mile away and running towards us were 60 group 4, and coming down the opposite end of the road were about the same number of police.

Now knowing that the Group 4 would almost definitely beat us up and the police only probably, we decided to run towards the police. We could not get the road due to a 20-foot metal sound barrier skiting down the side of the road. Our cars were nowhere to be seen as a crash had happened causing a massive tailback with our vehicles about half a mile away. About thirty seconds before we would have met with the police the jam cleared and our cars appeared. Two carloads raced off, resulting in more car chases but the police then blocked the road and six cars were left stranded, some even pushed onto the hard shoulder by police cars. The cars, the site, and everyone present were searched by the police, no tools were found. After all this was a bank holiday excursion of The Roadside Botanical Society. We were interested in the rare Yellow Cradwort, not horrible greasy monkey-wrenches. Two people were arrested under suspicion of criminal damage but were later released and the charges dropped. The whole fracas caused great inconvenience to many Mayday holidaymakers, These incidence happened on the North bound carriageways of the A33, causing a large traffic jam in both directions for 45 minutes. Oh dear!

May 4–21

Many EF! actions in other places, injunction hearings and gatherings etc. resulted in a drop of activity. The camp was also evicted by Ideal Homes and moved to an abandoned army camp nearby.

Greenfly, Market Gardens and the Pernicious Tarmac Weed On 22 May an amazing overnight action took place at Twyford Down. In order to stop Tarmac the planet wreckers from building a massive construction bridge over the bypass (codenamed Operation Market Garden by the Dept. of Roads), 300 activists gathered at the protest camp that day for the counter operation Operation Greenfly. There was an overwhelming sense of pessimism and helplessness as reccys had shown that Tarmac were preparing for battle by erecting razor wire barricades all around the site. Group 4, we learnt, had taken the precaution of hiring hundreds more guards and giving them instructions to use more than usual force. The police were there in large numbers and the situation looked pretty fucking scary.

Well, we worried, we work-shopped, we briefed, we painted our faces, gathered ourselves, and set off to get to the site before the bypass closed down for the night.

The procession of 200 activists looked amazing. Our courage and determination grew as we walked through the water meadows towards the ready built bridge which was about to be pushed across the road. The next sequence of events is amazing and shows what a group of determined people can do. It surprised even the most experienced and seasoned of activists. We formed into a tortoise formation, linked arms and marched onto the site. Rope was tied onto the razor wire, it was pulled away, the other fence was pulled onto it and we stormed in, united. There was nothing Group 4 or the police could do! As Paul said; We almost seemed to fly over the wire. It was as if we were carried. The greenfly buzzed all over the 30 foot high, 200 foot long bridge, WOW WHAT A FEELING!

For five hours we held that bridge, drumming into the night, until the police had to call in reinforcements from all over the south to get us down. By 2am, there were in total 550 police and 320 group. There were 52 arrests for obstruction of the police and the whole action had been carried out, from our side, with an amazing lack of aggression. It was so empowering. About another 150 people had gathered on the other side of the razor wire, fires burned, and a man breathed fire. On the bridge it was Party time. Night fell, the road closed down, the arc lights roared into action.

A horrific event unfolded as one activist, while under arrest, was run over by a Tarmac tractor and fuel tank. The driver, laughing, parked up on the site road obstructing an ambulance from entering. Darren received serious injuries and was critical for a while. Darren’s injuries included: a flailed left chest, (i.e. six multiply-broken ribs), a punctured and collapsed left lung, five pelvic fractures, a ruptured urethra, and a broken ankle. He remained in hospital for about a month and a half and was on crutches for longer.

Meanwhile the rest of the action was going much better. We drummed on the monster structure and the deafening metallic beat echoed across the valley. One man climbed a 40 foot lighting rig and flew the dragon flag and the dragon dancers took the road!

A bank of TV cameras and press photographers lapped up this spectacular action, there was live footage on TV. It was splashed all over the national press the next day.

What was not reported was that, according to Blackwells, during that morning several excavators and water pumps had been trashed. That night as the greenfly fired up the night on the bridge, elsewhere an excavator was torched, a stretch of Tarmac burned and part of the work site flooded. People have cost Tarmac and the DoT millions in lost time and damaged machinery.

May 24—July 1

No major action happened at Twyford in this period. The time was taken up with a concoction of smaller actions, court cases and even an invasion of Tarmac’s AGM in London on the 16th of June. There was a large Twyford contingent at Glastonbury festival, (a consumer hype if ever I saw one), who gave talks and direct action training all through the festival.

July 2