Original Essays:

• Comrades of Kaczynski Winter Solstice

Excerpts of Republished Essays:

• Conspiracy is Unnecessary

• A chronology of unabomb related events (unknown author)

• Thinking about Violence (unknown author)

• Anarchy in the USA by Peter Klebnikov (Gear Magazine)

• Defending the Unabomber

• I Don't Want To Live Long: Ted Kaczynski

• The Unabomber's Legacy

• Unabomber Fans

• WHOSE UNABOMBER?

• Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us

• Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber

Republished Essays in Full:

• Progress versus Liberty

• Ship of Fools

• Morality and Revolution

• Interview—Ted Kaczynski

• UNABOM: 4/20/95 letter to the New York Times

• Representing Ted Kaczynski

Comrades of Kaczynski

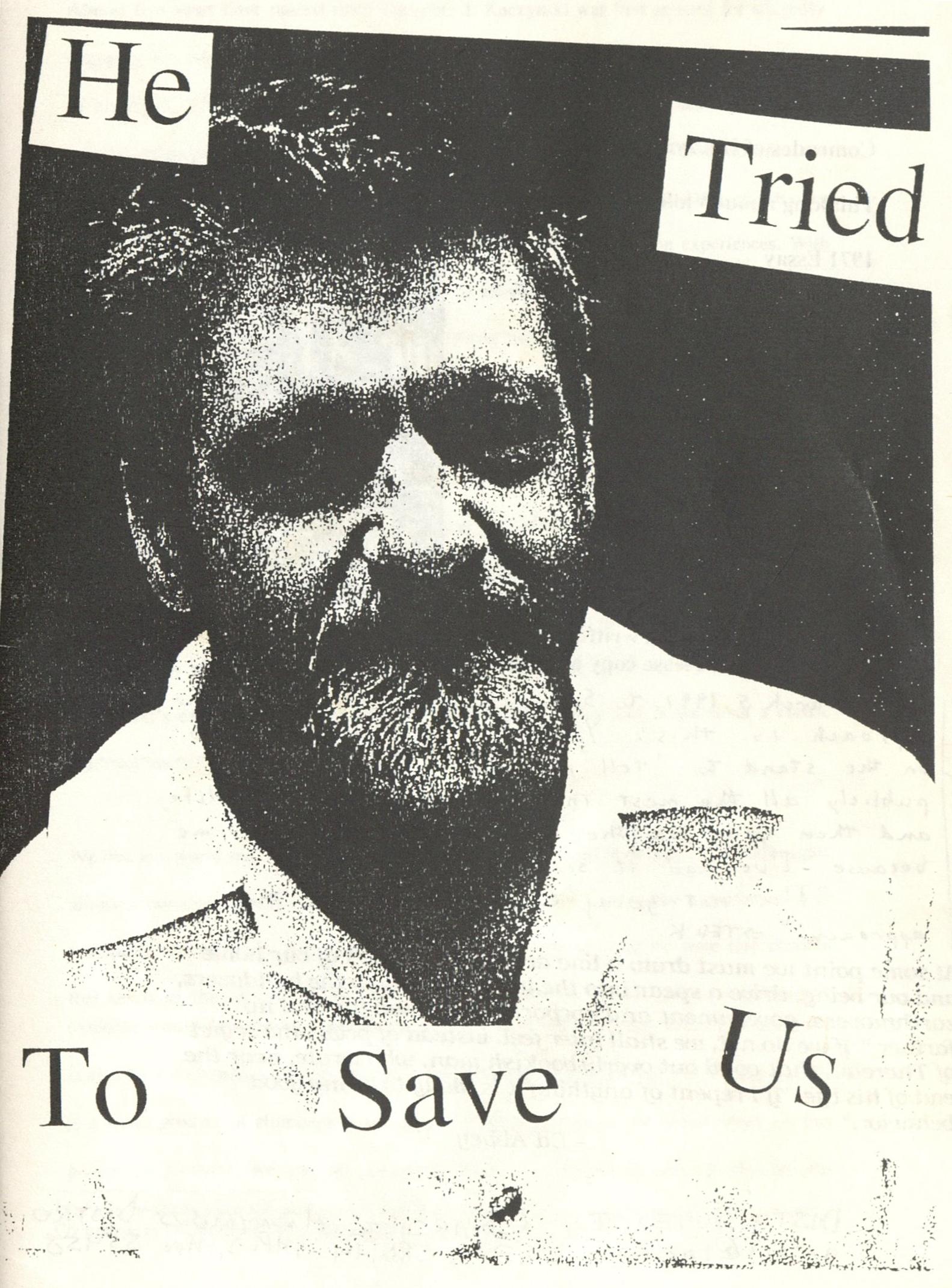

He tried to save us

Comrades of Kaczynski Winter Solstice

Defending the Unabomber. Mar. 16 1998 The New Yorker

Gear Magazine, Anarchy in the USA, by Peter Klebnikov.

The Unabomber's Legacy, Part I

Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,

Excerpts from: Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber By Alston Chase

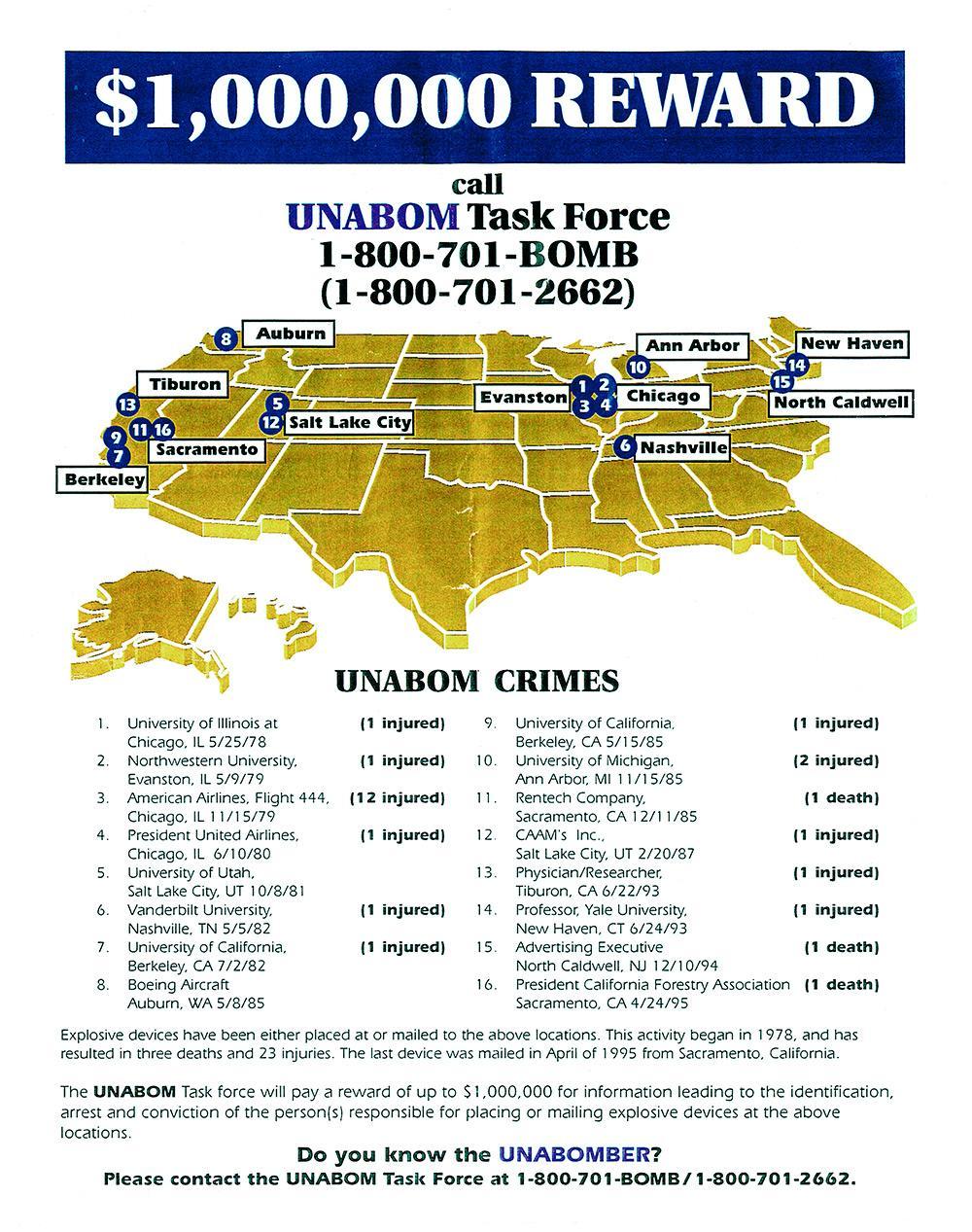

a chronology of unabomb related events…

UNABOM: 4/20/95 letter to the New York Times

Representing Ted Kaczynski: The Right to Assistance of Counsel

[Front Matter]

Table of Contents:

-

Comrades of Kaczynski Winter Solstice

-

Thinking about Violence

-

1971 Essay

-

Ship of Fools

-

Selections from Articles

-

Morality and Revolution

-

Chronology of Events

-

Selections from Interview

Publisher Details

Sorry, no page numbers. Figure it out.

Published, edited, and written by Comrades of Kaczynski Anti-Copyright Please copy and steal as you wish.

[Note written by Kaczynski on his copy:] March 5, 1997, to Sowards and Holdman: “Your approach is this: You put a shrink or two on the stand to ‘tell my story,’ you expose publicly all the most intimate details of my life and then you ask the jury to take pity on me because I’ve had it so tough.

“I’m not going to let you take this approach.” => Ted K.

Epigraph

At some point we must draw a line across the ground of our home and our being, drive a spear into the land and say to the bulldozers, earthmovers, government and corporations, "thus far and no further." If we do not, we shall later feel, instead of pride, the regret of Thoreau, that good but overly-bookish man, who wrote, near the end of his life, "If I repent of anything it is likely to be my good behaviour."

- Ed Abbey

[Note written by Kaczynski on his copy:] DISTRIBUTED BY ANARCHISTS ANONYMOUS DISTRO g-spot@tao.cz P.O. Box [text cut off], 55458

Comrades of Kaczynski Winter Solstice

Almost five years have passed since Theodore J. Kaczynski was first arrested for allegedly engaging in a seventeen-year, anti-technology anarchistic bombing campaign. From the time of his April, 1996 arrest, to his forced confession and guilty plea in January, 1998 and beyond, many pressing questions were raised. Anyone with a political consciousness no doubt recognized the Pandora’s box Kaczynski opened. Kaczynski was acting on passions and sorrows similar to what everyone living under modem civilization experiences. With huge amounts of the world population on mind-altering psychiatric or illicit substances to simply survive, it makes me wonder if there has ever been anything “normal” or “sane” about the way most modem civilized people live.[1] Almost anyone living in a city in America could be diagnosed with some psychological disorder.

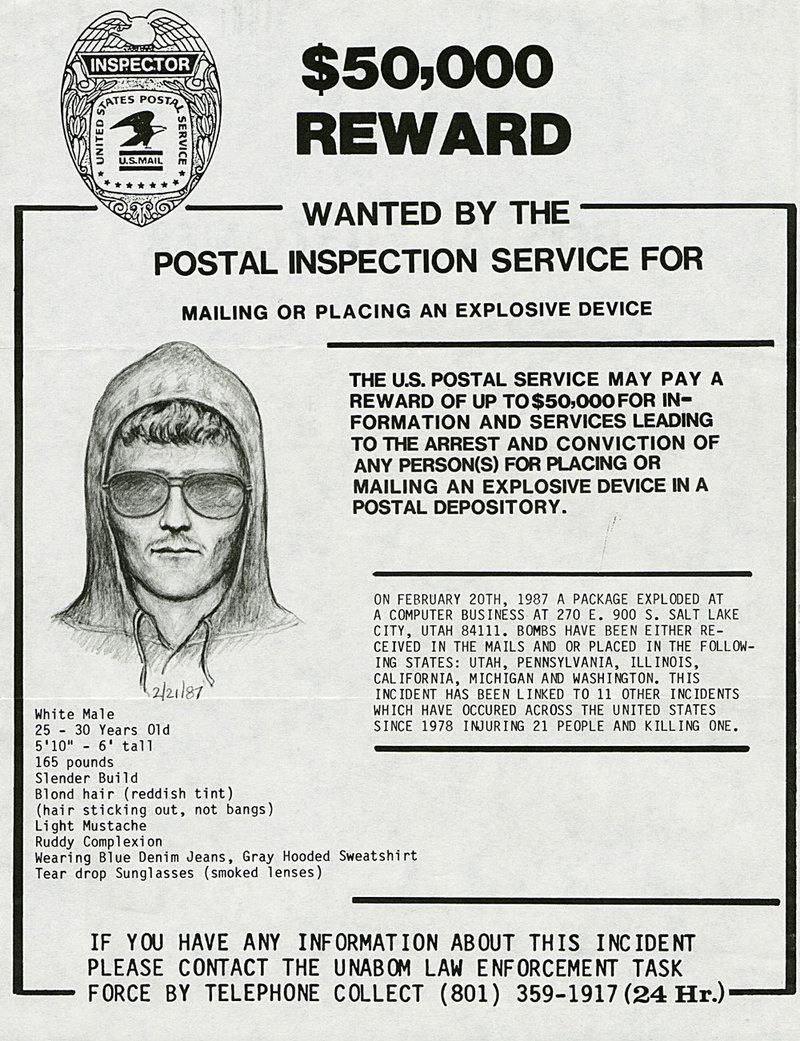

Those of us opposed to the mass psychological (and physical) misery that dominates daily life are oft times labeled crazy, insane, or stupid and mislead. In England, Soviet Russia, and countless other places, those in power have a history of labeling dissidents as mentally ill and locking them away in institutions, or, worse yet, lobotomizing them into submission. In Kaczynski’s case, simply jailing him and providing the media with a sketch of a classic madman seemed to suffice.

We live in a world engulfed by propaganda; it is sometimes hard to distinguish what thoughts are even our own. Surely no one would have a spontaneous urge to buy a product such as toothpaste with fluoride. No—it is the barrage of information since we were tiny children that sends us the ’desire’ to buy fluoride-laden toothpaste If that 'desire' is examined, evidence would demonstrate that fluoride not only does not slow tooth decay past age 15, it is also toxic to humans. Imagine how surprising it would be to find out that sodium fluoride is a waste product of aluminum manufacture. Assuming most people would rather not buy poisonous products, we can see that the ‘desire’ to consume fluoride toothpaste was manufactured to serve the interests of industry and capitalism.

An examination into the case of political prisoner, Ted Kaczynski will reveal a similar propaganda campaign. Before passing judgment on this serious revolutionary matter, reconsider your ideas of morality, technology, justice and violence. It is only by thinking beyond the confines of a state-sponsored, propaganda-driven paradigm that the truth of the Kaczynski situation can finally be understood.

In the rest of this booklet—especially in the excerpts from the New Yorker article—it is made clear that the portrayal of Kaczynski as a madman was entirely false. Everyone who interacted with Kaczynski—including the judge presiding over his case—found him to be quite rational and sane, especially under the tremendous pressure of a potential death sentence. His lawyers and consequently the mass-media used photographs, psychiatric evaluations (more often than not from doctors that had never even met Kaczynski), and, most insultingly, his cabin from Montana to paint a picture of a crazy hermit. His lawyers intended on showing the cabin to the jury and asking, “would any sane person choose to live in such a primitive manner?”[2] Although a government psychiatrist deemed Kaczynski fit to stand trial and represent himself, the image of a lunatic still dominates public attitude. Even many anarchists and political activists I know call Kaczynski a murderer and a psychopath for mailing bombs. People have assumed his guilt from the start based on nothing but what the FBI has told us they found in Kaczynski’s cabin, (and we all know how trustworthy the FBI is!)

In light of the chain of events that led to Ted's forced confession, and the evidence that he is as sane as any of us, it becomes obvious that the masses have been duped once again. If we are intent on challenging the govemmental/corporate machine, we must start to draw some of our own conclusions.

This conflict of a television image vs. reality is much too familiar. In my personal experience, accounts of a protest or demonstration on the news have been consistently disappointing and discouraging. For example, at the BIO 2000 protests in Boston, Massachusetts, the vivid and hugely attended demonstrations were not shown on mainstream news. Instead, the police and city officials rejoiced with business owners over the fact that their windows weren't smashed. As usual, the media—the propaganda tools of the powers- that-be—are quick to avoid reporting anything critical of the people who sign their paychecks. I urge you to search out this information on your own and let subjectivity guide you to more reasonable ideas about Kaczynski and his case, and the information systems that envelop us. Perhaps some will even choose to support Kaczynski, and fight for his freedom; as many have for Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal—both in jail for the same crime as Kaczynski’s: murder.

Clemency for Leonard Peltier is now closer than ever. The papers sit on the president's desk as this is being written. If he is set free, it will be because there is some benefit to the state, and as a result of the pressure put on the government by Native Americans and prison activists. Mumia Abu-Jamal has almost been put to death; saved due to the threat posed by activists and others if he were to be killed. Many millions of people support both of these political prisoners, yet know little of Kaczynski; of those who do, all but a few think him insane.

Peltier is convicted of killing two federal agents; Mumia, a cop. In both situations, it matters little to me whether they committed these “crimes.” What matters is that they are revolutionaries in jail and they need our solidarity and support. People who still have faith in the legal system believe the two have been short-changed and should have new trials. Kaczynski’s legal battle, as described in the New Yorker excerpts, at the very least demands a new trial. His 6th amendment right to represent himself was denied, and he was forced to proceed with lawyers he disagreed with. It was only after the judge denied both this and the request for new lawyers that Kaczynski plead guilty.

I am an anarchist, and therefore believe that a new trial would be useless. The state will always serve the interests of the state. Kaczynski, Peltier, Mumia and all political prisoners must be freed, and if the state will not release them (HA!), than we must do it ourselves. In Greece, when anarchists are imprisoned, their comrades have set bombs, taken over buildings and militantly demonstrated to support them. On many occasions, the IRA killed prison guards who were reportedly torturing and harassing Republican inmates in the English prisons. Their actions would force the guards to ease up for fear of retribution. Nikos Maziotis, Greek anarchist prisoner, stated, “solidarity with all hostages of the state and capital, with Mumia Abu-Jamal, Leonard Peltier, Theodore Kaczynski and Tupac Amaru." Kaczynski is as political of a prisoner as they come. I believe Ted should be supported whether or not he committed the “crimes" he is convicted of. If he did not, he has been framed, he is a self-proclaimed revolutionary. If he did do the bombings, then he was striking blows against the system, and, is our comrade.[3]

One of the more important byproducts of Kaczynski's case was the exposure of the fascism of justice. The “rights" normally allocated to those accused of “crimes” were systematically stripped from the beginning with the raid of his cabin. The FBI went in without witnesses from the local police department, which is a legal requirement for such a raid.[4] The only evidence was David Kaczynski’s testimony that the Manifesto was similar to Ted’s writings.

After this shocking violation of his rights, Ted was later forced to be represented by lawyers who would not allow him to use a political defense. His rights to representation and to represent himself were stripped by the Judge because his requests were "untimely." What this amounts to is an illumination of what our so-called “rights" truly encompass.

To prevent revolt, government must allocate to its constituency some sort of power This power is doled out to us in the form of rights. These rights, as guaranteed by many laws, supposedly make us free. Although they are "unalienable,” we have seen that when the state is threatened, our "rights” can be quickly taken away. Rights turn out to be a complex tool to control the population, and when they are not enough to suffice, are removed. Justice has been defined as ‘vindictive retribution’ or ‘due punishment for a crime.’[5] A crime is something that falls into the wrong category of what the state has defined as right and wrong. Since crime is a state-defined idea, then justice inherently is as well. We must understand that “crime," is a loaded and degrading word, as such, no one should be jailed, for justice is guilty.

People everywhere, even the privileged of America, are beginning to feel the emptiness that is prevalent in the human psyche. This void grows bigger as our experiences with the natural world become increasingly mediated. Technology, in all its forms, has aided this mediating process, and indeed helped it expand to cover the whole planet. Not only civilized philosophy, but the physical effects of civilization are everywhere: the hole in the ozone, radiation clouds from wars, nuclear accidents and testing, jet fuel residue found in deep icecore samples in the arctic, dioxin in our water, office and school shootings on the rise; anyone can add to the list. The natural chaos of life is being destroyed by this civilized “order.” How could anyone who tries to halt this death march be called anything but reasonable? I would hope all humans feel some sense of obligation to the planet; enough to defend what wild remains.

But what can we do? What can one person possibly do? In the sample of articles provided in this booklet—taken from the thousands that were written—what one person did blew a crack in the prevailing paradigm. People were forced to consider why someone would kill for the wild and what is left of it in humans. Conspiracy is unnecessary. It has been demonstrated that one person can affect tremendous change. It’s a matter of scale. A one-man bombing campaign or an all out war against those who would destroy everything that makes life worth living.

Comrades of Kaczynski

Winter Solstice communiqué

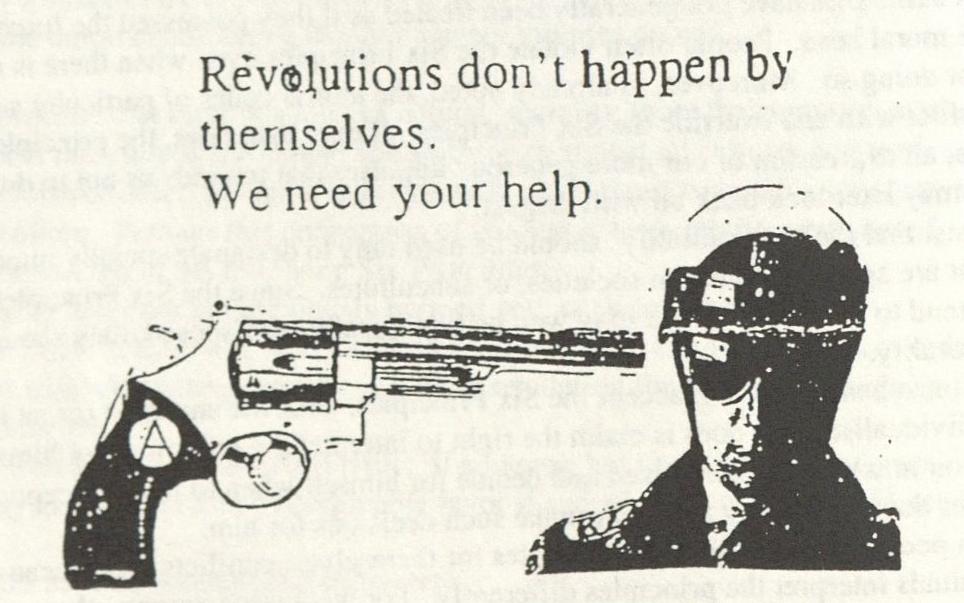

Thinking about Violence

Violence:

1. Physical force exerted for the purpose of violating, damaging, or abusing: crimes of violence. 2. Abusive or unjust exercise of power. Political prisoners Linda Evans and Laura Whitehorn, in jail since 1985 for conspiring to "influence, change and protest policies and practices of the US government" with a series of bombings, address 'violence' in response to an interviewer's question:

Interviewer: Audre Lorde says the master's tools (violence) will never dismantle the master's house (the state). How do you react to this?

Laura: I don't think "violence" is just one thing, so I don't think it's necessarily ' the master's tool". If revolutionaries were as vicious and careless of humanity and innocent human lives as the U.S. government is, then I think we'd be doing wrong. But when oppressed people fight for freedom, using "violent" means among others, I think we should support them. Would you have condemned African slaves in the U.S. for killing their slave masters, or for using violence in a struggle for freedom?

Linda: I don't think the issue is violence, but rather politics and power. Around the world, imperialism maintains itself by military power and the threat of violence wherever people struggle for change. Liberation movements have the right to use every means available to defeat the system that is oppressing and killing people. This means fighting back in self-defense. A slogan that embodies this for me comes from the Chinese Revolution: "Without mass struggle, there can be no revolution. Without armed struggle, there can be no victory."

Peaceniks that mobilize for every march and carry on their meaningless pleas for reform (and even those have lost any usefulness) are always quick to label any kind of aggressive or militant action as violence and thus condemn the militants. Even an issue as mild as smashing a few corporate windows draws criticism from privileged activist circles. But how can the same term encompass both the horrors of capitalism and civilization against the planet and the self-defense actions taken by a few individuals who have grown tired of waving signs and begging for freedom?

When someone like Ted Kaczynski is mentioned, even seasoned anarchists cop out and judge his actions based on criteria that has been predetermined by the state Anyone who dismisses the actions and lifestyle of Kaczynski as violent and insane fails to realize the extremity of the problems we face due to hierarchical control and the mass-accepted status quo. It is no longer a question of violence vs. nonviolence. As Ward Churchill makes clear in Pacifism as Pathology, It is a question of when violence is necessary.

In a world where our lives are floating on the edge of ecological catastrophe, our outlets of rage cannot be written off as violent. Any actions taken against this rotting order must be seen as self-defense, thereby nullifying the debate over violence and allowing us a praxis of subjectivity. Along with this comes the freedom to choose our actions as we see fit, without the constraints applied by the terminology of violence.

Where do we go from here? Laura Whitehorn says it best, "Fight it. Don't back away. Develop clandestine ways of operating so that the state won't know everything that you’re doing. Support one another so that, when anyone is targeted for state attack, they can resist - that resistance will build us all. Don't ever give information - even if you think it’s "safe" information - to the state. Don't let the state divide the movement by calling some groups "legitimate" and others not. Unity is our strength. Support other movements and people who are also targets of state attack. When the state calls someone a "terrorist", or "violent", or "crazy", or anything, think hard before ever believing it to be true. Resist. Resist. Resist."

1971 Essay

In these pages it is argued that continued scientific and technical progress will inevitably result in the extinction of individual liberty. I use the word “inevitably” in the following sense: One might—possibly—imagine certain conditions of society in which freedom could coexist with unfettered technology, but these conditions do not actually exist, and we know of no way to bring them about, so that, in practice, scientific progress will result in the extinction of individual liberty. Toward the end of this essay we propose what appears to be the only thing that bears any resemblance to a practical remedy for this situation.

I hope that the reader will bear with me when I recite arguments and facts with which he may already be familiar. I make no claim to originality. I simply think that the case for the thesis stated above is convincing, and I am attempting to set forth the arguments, new and old, in as clear a manner as possible, in the hope that the reader will be persuaded to support the solution here suggested—which certainly is a very obvious solution, but rather hard for many people to swallow.

The power of society to control the individual person has recently been expanding very rapidly, and is expected to expand even more rapidly in the near future. Let us list a few of the more ominous developments as a reminder.

1. Propaganda and image-making techniques. In this context we must not neglect the role of movies, television, and literature, which commonly are regarded either as art or as entertainment, but which often consciously adopt certain points of view and thus serve as propaganda. Even when they do not consciously adopt an explicit point of view they still serve to indoctrinate the viewer or reader with certain values. We venerate the great writers of the past, but one who considers the matter objectively must admit that modern artistic techniques have developed to the point where the more skillfully constructed movies, novels, etc. of today are far more psychologically potent than, say, Shakespeare ever was. The best of them are capable of gripping and involving the reader very powerfully and thus are presumably quite effective in influencing his values. Also note the increasing extent to which the average person today is “living in the movies” as the saying is. People spend a large and increasing amount of time submitting to canned entertainment rather than participating in spontaneous activities. As overcrowding and rules and regulations curtail opportunities for spontaneous activity, and as the developing techniques of entertainment make the canned product ever more attractive, we can assume that people will live more and more in the world of mass entertainment.

2. A growing emphasis among educators on “guiding” the child’s emotional development, coupled with an increasingly scientific attitude toward education. Of course, educators have always in some degree attempted to mold the attitudes of their pupils, but formerly they achieved only a limited degree of success, simply because their methods were unscientific. Educational psychology is changing this.

3. Operant conditioning, after the manner of B.F. Skinner and friends. (Of course, this cannot be entirely separated from item (2)).

4. Direct physical control of the emotions via electrodes and “chemitrodes” inserted in the brain. (See Jose M.R. Delgado’s book “Physical Control of the Mind.”)

5. Biofeedback training, after the manner of Joseph Kamiya and others.

6. Predicted “memory pills” or other drugs designed to improve memory or increase intelligence. (The reader possibly assumes that items (5) and (6) present no danger to freedom because their use is supposed to be voluntary, but I will argue that point later. See page 8.)

7. Predicted genetic engineering, eugenics, related techniques.

8. Marvin Minsky of MIT (one of the foremost computer experts in the country) and other computer scientists predict that within fifteen years or possibly much less there will be superhuman computers with intellectual capacities far beyond anything of which humans are capable. It is to be emphasized that these computers will not merely perform so-called “mechanical” operations; they will be capable of creative thought. Many people are incredulous at the idea of a creative computer, but let it be remembered that (unless one resorts to supernatural explanations of human thought) the human brain itself is an electro-chemical computer, operating according to the laws of physics and chemistry. Furthermore, the men who have predicted these computers are not crackpots but first-class scientists. It is difficult to say in advance just how much power these computers will put into the hands of what is vulgarly termed the establishment, but this power will probably be very great. Bear in mind that these computers will be wholly under the control of the scientific, bureaucratic, and business elite. The average person will have no access to them. Unlike the human brain, computers are more or less unrestricted as to size (and, more important, there is no restriction on the number of computers that can be linked together over a long distance to form a single brain), so that there is no restriction on their memories or on the amount of information they can assimilate and correlate. Computers are not subject to fatigue, daydreaming, or emotional problems. They work at fantastic speed. Given that a computer can duplicate the functions of the human brain, it seems clear in view of the advantages listed above that no human brain could possibly compete with such a computer in any field of endeavor.

9. Various electronic devices for surveillance. These are being used. For example, according to newspaper reports, the police of New York City have recently instituted a system of 24-hour television surveillance over certain problem areas of the city.

These are some of the more strikingly ominous facets of scientific progress, but it is perhaps more important to look at the effect of technology as a whole on our society. Technological progress is the basic cause of the continual increase in the number of rules and regulations. This is because many of our technological devices are more powerful and therefore more potentially destructive than the more primitive devices they replace (e.g., compare autos and horses) and also because the increasing complexity of the system makes necessary a more delicate coordination of its parts. Moreover, many devices of functional importance (e.g., electronic computers, television broadcasting equipment, jet planes) cannot be owned by the average person because of their size and costliness. These devices are controlled by large organizations such as corporations and governments and are used to further the purposes of the establishment. A larger and larger proportion of the individual’s environment—not only his physical environment, but such factors as the kind of work he does, the nature of his entertainment, etc.–comes to be created and controlled by large organizations rather than by the individual himself. And this is a necessary consequence of technological progress, because to allow technology to be exploited in an unregulated, unorganized way would result in disaster.

Note that the problem here is not simply to make sure that technology is used only for good purposes. In fact, we can be reasonably certain that the powers which technology is putting into the hands of the establishment will be used to promote good and eliminate evil. These powers will be so great that within a few decades virtually all evil will have been eliminated. But, of course, “good” and “evil” here mean good and evil as interpreted by the social mainstream. In other words, technology will enable the social mainstream to impose its values universally. This will not come about through the machinations of power-hungry scoundrels, but through the efforts of socially responsible people who sincerely want to do good and who sincerely believe in freedom—but whose concept of freedom will be shaped by their own values, which will not necessarily be the same as your values or my values.

The most important aspect of this process will perhaps be the education of children, so let us use education as an example to illustrate the way the process works. Children will be taught—by methods which will become increasingly effective as educational psychology develops—to be creative, inquiring, appreciative of the arts and sciences, interested in their studies—perhaps they will even be taught nonconformity. But of course this will not be merely random nonconformity but “creative” nonconformity. Creative nonconformity simply means nonconformity that is directed toward socially desirable ends. For example, children may be taught (in the name of freedom) to liberate themselves from irrational prejudices of their elders, “irrational prejudices” being those values which are not conducive to the kind of society that most educators choose to regard as healthy. Children will be educated to be racially unbiased, to abhor violence, to fit into society without excessive conflict. By a series of small steps—each of which will be regarded not as a step toward behavioral engineering but as an improvement in educational technique—this system will become so effective that hardly any child will turn out to be other than what the educators desire. The educational system will then have become a form of psychological compulsion. The means employed in this “education” will be expanded to include methods which we currently would consider disgusting, but since these methods will be introduced in a series of small steps, most people will not object—especially since children trained to take a “scientific” or “rational” attitude toward education will be growing up to replace their elders as they die off.

For instance, chemical and electrical manipulation of the brain will at first be used only on children considered to be insane, or at least severely disturbed. As people become accustomed to such practices, they will come to be used on children who are only moderately disturbed. Now, whatever is on the furthest fringes of the abnormal generally comes to be regarded with abhorrence. As the more severe forms of disturbances are eliminated, the less severe forms will come to constitute the outer fringe; they will thus be regarded as abhorrent and hence as fair game for chemical and electrical manipulation. Eventually, all forms of disturbance will be eliminated—and anything that brings an individual into conflict with his society will make him unhappy and therefore will be a disturbance. Note that this whole process does not presuppose any antilibertarian philosophy on the part of educators or psychologists, but only a desire to do their jobs more effectively.

Consider: Today, how can one argue against sex education? Sex education is designed not simply to present children with the bald facts of sex; it is designed to guide children to a healthy attitude toward sex. And who can argue against that? Think of all the misery suffered as a result of Victorian repressions, sexual perversions, frigidity, unwanted pregnancies, and venerial [sic.] disease. If much of this can be eliminated by instilling “healthy” (as the social mainstream interprets that word) sexual attitudes in children, who can deny it to them? But it will be equally impossible to argue against any of the other steps that will eventually lead to the complete engineering of the human personality. Each step will be equally humanitarian in its goals.

There is no distinct line between “guidance” or “influence” and manipulation. When a technique of influence becomes so effective that it achieves its desired effect in nearly every case, then it is no longer influence but compulsion. Thus influence evolves into compulsion as science improves technique.

Research has shown that exposure to television violence makes the viewer more prone to violence himself. The very existence of this knowledge makes it a foregone conclusion that restrictions will eventually be placed on televized violence, either by the government or by the TV industry itself, in order to make children less prone to develop violent personalities. This is an element of manipulation. It may be that you feel an end to television violence is desirable and that the degree of manipulation involved is insignificant. But science will reveal, one at a time, a hundred other factors in entertainment that have a “desirable” or “undesirable” effect on personality. In the case of each one of these factors, knowledge will make manipulation inevitable. When the whole array of factors has become known, we will have drifted into large-scale manipulation. In this way, research leads automatically to calculated indoctrination.

By way of a further example, let us consider genetic engineering. This will not come into use as a result of a conscious decision by the majority of people to introduce genetic engineering. It will begin with certain “progressive” parents who will voluntarily avail themselves of genetic engineering opportunities in order to eliminate the risk of certain gross physical defects in their offspring. Later, this engineering will be extended to include elimination of mental defects and treatment which will predispose the child to somewhat higher intelligence. (Note that the question of what constitutes a mental “defect” is a value-judgement. Is homosexuality, for example, a defect? Some homosexuals would say “no.” But there is no objectively true or false answer to such a question.) As methods are improved to the point where the minority of parents who use genetic engineering are producing noticeably healthier, smarter offspring, more and more parents will want genetic engineering. When the majority of children are genetically engineered, even those parents who might otherwise be antagonistic toward genetic engineering will feel obliged to use it so that their children will be able to compete in a world of superior people—superior, at least relative to the social milieu in which they live. In the end, genetic engineering will be made compulsory because it will be regarded as cruel and irresponsible for a few eccentric parents to produce inferior offspring by refusing to use it. Bear in mind that this engineering will involve mental as well as physical characteristics; indeed, as scientists explain mental traits on the basis of physiology, neurology, and biochemistry, it will become more and more difficult to distinguish between “mental” and “physical” traits.

Observe that once a society based on psychological, genetic, and other forms of human engineering has come into being, it will presumably last forever, because people will all be engineered to favor human engineering and the totally collective society, so that they will never become dissatisfied with this kind of society. Furthermore, once human engineering, the linking of human minds with computers, and other things of that nature have come into extensive use, people will probably be altered so much that it will no longer be possible for them to exist as independent beings, either physically or psychologically. Indeed, technology has already made it impossible for us to live as physically independent beings, for the skills which enabled primitive man to live off the country have been lost. We can survive only by acting as components of a huge machine which provides for our physical needs; and as technology invades the domain of mind, it is safe to assume that human beings will become as dependent psychologically on technology as they now are physically. We can see the beginning of this already in the inability of some people to avoid boredom without television and in the need of others to use tranquilizers in order to cope with the tensions of modern society.

The foregoing predictions are supported by the opinions of at least some responsible writers. See especially Jacques Ellul’s “The Technological Society” and the section titled “Social Controls” in Kahn and Wiener’s “The Year 2,000.”

Now we come to the question: What can be done to prevent all this? Let us first consider the solution sketched by Perry London in his book “Behavior Control.” This solution makes a convenient example because its defects are typical of other proposed solutions. London’s idea is, briefly, this: Let us not attempt to interfere with the development of behavioral technology, but let us all try to be as aware of and as knowledgeable about this technology as we can; let us not keep this technology in the hands of a scientific elite, but disseminate it among the population at large; people can then use this technology to manipulate themselves and protect themselves from manipulation by others. However, on the grounds that “there must be some limits” London advocates that behavior control should be imposed by society in certain areas. For example, he suggests that people should be made to abhor violence and that psychological means should be used to make businessmen stop destroying the forests. (NOTE: I do not currently have access to a copy of London’s book, and so I have had to rely on memory in describing his views. My memory is probably correct here, but in order to be honest I should admit the possibility of error.)

My first objection to London’s scheme is a personal one. I simply find the sphere of freedom that he favors too narrow for me to accept. But his solution suffers from other flaws.

He proposes to use psychological controls where they are not necessary, and more for the purpose of gratifying the liberal intellectual’s esthetic sensibilities than because of a practical need. It is true that “there must be some limits”–on violence, for example—but the threat of imprisonment seems to be an adequate limitation. To read about violence is frightening, but violent crime is not a significant cause of mortality in comparison to other causes. Far more people are killed in automobile accidents than through violent crime. Would London also advocate psychological elimination of those personalities that are inclined to careless driving? The fact that liberal intellectuals and many others get far more excited over violence than they do over careless driving would seem to indicate that their antagonism toward violence arises not primarily from a concern for human life but from a strong emotional antipathy toward violence itself. Thus it appears that London’s proposal to eliminate violence through psychological control results not from practical necessity but from a desire on London’s part to engineer some of his own values into the public at large.

This becomes even clearer when we consider London’s willingness to use psychological engineering to stop businessmen from destroying forests. Obviously, psychological engineering cannot accomplish this until the establishment can be persuaded to carry out the appropriate program of engineering. But if the establishment can be persuaded to do this, then they can equally well be persuaded to pass conservation laws strict enough to accomplish the same purpose. And if such laws are passed, the psychological engineering is superfluous. It seems clear that here, again, London is attracted to psychological engineering simply because he would like to see the general public share certain of his values.

When London proposes to us systematic psychological controls over certain aspects of the personality, with the intention that these controls shall not be extended to others areas, he is assuming that the generation following his own will agree with his judgment as to how far the psychological controls should reach. This assumption is almost certainly false. The introduction of psychological controls in some areas (which London approves) will set the stage for the later introduction of controls in other areas (which London would not approve), because it will change the culture in such a way as to make people more receptive to the concept of psychological controls. As long as any behavior is permitted which is not in the best interests of the collective social organization, there will always be the temptation to eliminate the worst of this behavior through human engineering. People will introduce new controls to eliminate only the worst of this behavior, without intending that any further extension of the controls should take place afterward; but in fact they will be indirectly causing further extensions of the controls because whenever new controls are introduced, the public, as it becomes used to the controls, will change its conception of what constitutes an appropriate degree of control. In other words, whatever the amount of control to which people have become accustomed, they will regard that amount as right and good and they will regard a little further extension of control as negligible price to pay for the elimination of some form of behavior that they find shocking.

London regards the wide dissemination of behavioral technology among the public as a means by which the people can protect themselves against psychological manipulation by the established powers. But if it is really true that people can use this knowledge to avoid manipulation in most areas, why won’t they also be able to use it to avoid being made to abhor violence, or to avoid control in other areas where London thinks they should be controlled? London seems to assume that people will be unable to avoid control in just those areas where he thinks they should be controlled, but that they will be able to avoid control in just those areas where he thinks they should not be controlled.

London refers to “awareness” (of sciences relating to the mind) as the individual’s “sword and buckler” against manipulation by the establishment. In Roman times a man might have a real sword and buckler just as good as those of the emperor’s legionaries, but that did not enable him to escape oppression. Similarly, if a man of the future has a complete knowledge of behavioral psychology it will not enable him to escape psychological control any more than the possession of a machine-gun or a tank would enable him to escape physical control. The resources of an organized society are just too great for any individual to resist no matter how much he knows.

With the vast expansion of knowledge in the behavioral sciences, biochemistry, cybernetics, physiology, genetics, and other disciplines which have the potential to affect human behavior, it is probably already impossible (and, if not, it will soon become impossible) for any individual to keep abreast of it all. In any case, we would all have to become, to some degree, specialists in behavior control in order to maintain London’s “awareness.” What about those people who just don’t happen to be attracted to that kind of science, or to any science? It would be agony for them to have to spend long hours studying behavioral technology in order to maintain their freedom.

Even if London’s scheme of freedom through “awareness” were feasible, it could, or at least would, be carried out only by an elite of intellectuals, businessmen, etc. Can you imagine the members of uneducated minority groups, or, for that matter, the average middle-class person, having the will and the ability to learn enough to compete in a world of psychological manipulation? It will be a case of the smart and the powerful getting more powerful while the stupid and the weak get (relatively) stupider and weaker; for it is the smart and the powerful who will have the readiest access to behavioral technology and the greatest ability to use it effectively.

This is one reason why devices for improving one’s mental or psychological capabilities (e.g., biofeedback training, memory pills, linking of human minds with computers) are dangerous to freedom even though their use is voluntary. For example, it will not be physically possible for everyone to have his own full-scale computer in his basement to which he can link his brain. The best computer facilities will be reserved for those whom society judges most worthy: government officials, scientists, etc. Thus the already powerful will be made more powerful.

Also, the use of such mind-augmentation devices will not remain voluntary. All our modern conveniences were originally introduced as optional benefits which one could take or leave as one chose. However, as a result of the introduction of these benefits, society changed its structure in such a way that the use of modern conveniences is now compulsory: for it would be physically impossible to live in modern society without extensively using devices provided by technology. Similarly, the use of mind-augmenting devices, though nominally voluntary, will become in practice compulsory. When these devices have reached a high development and have come into wide use, a person refusing to use them would be putting himself in the position of a dumb animal in a world of supermen. He would simply be unable to function in a society structured around the assumption that most people have vastly augmented mental abilities.

By virtue of their very power, the devices for augmenting or modifying the human mind and personality will have to be governed by extensive rules and regulations. As the human mind comes to be more and more an artifact created by means of such devices, these rules and regulations will come to be rules and regulations governing the structure of the human mind.

An important point: London does not even consider the question of human engineering in infancy (let alone genetic engineering before conception). A two-year-old obviously would not be able to apply London’s philosophy of “awareness”; yet it will be possible in the future to engineer a young child so that he will grow up to have the type of personality that is desired by whoever has charge of him. What is the meaning of freedom for a person whose entire personality has been planned and created by someone else?

London’s solution suffers from another flaw that is of particular importance because it is shared by all libertarian solutions to the technology problem that have ever come to my attention. The problem is supposed to be solved by propounding and popularizing a certain libertarian philosophy. This approach is unlikely to achieve anything. Our liberty is not deteriorating as a result of any antilibertarian philosophy. Most people in this country profess to believe in freedom. Our liberty is deteriorating as a result of the way people do their jobs and behave in relation to technology on a day-to-day basis. The system has come to be set up in such a way that it is usually comfortable to do that which strengthens the organization. When a person in a position of responsibility sets to eliminate that which is contrary to established values, he is rewarded with the esteem of his fellows and in other ways. Police officials who introduce new surveillance devices, educators who introduce more advanced techniques for molding children, do not do so through disrespect for freedom; they do so because they are rewarded with the approval of other police officials or educators and also because they get an inward satisfaction from having accomplished their assigned tasks not only competently, but creatively. A hands-off approach toward the child’s personality would be best from the point of view of freedom, but this approach will not be taken because the most intelligent and capable educators crave the satisfaction of doing their work creatively. They want to do more with the child, not less. The greatest reward that a person gets from furthering the ends of the organization may well be simply the opportunity for purposeful, challenging, important activity—an opportunity that is otherwise hard to come by in society. For example, Marvin Minsky does not work on computers because he is antagonistic to freedom, but because he loves the intellectual challenge. Probably he believes in freedom, but since he is a computer specialist he manages to persuade himself that computers will tend to liberate man.

The main point here is that the danger to freedom is caused by the way people work and behave on a day-to-day basis in relation to technology; and the way people behave in relation to technology is determined by powerful social and psychological forces. To oppose these forces a comparatively weak force like a body of philosophy is simply hopeless. You may persuade the public to accept your philosophy, but most people will not significantly change their behavior as a result. They will invent rationalizations to reconcile their behavior with the philosophy, or they will say that what they do as individuals is too insignificant to change the course of events, or they will simply confess themselves too weak to live up to the philosophy. Conceivably a school of philosophy might change a culture over a long period of time if the social forces tending in the opposite direction were weak. But the social forces guiding the present development of our society are obviously strong, and we have very little time left—another three decades likely will take us past the point of no return.

Thus a philosophy will be ineffective unless that philosophy is accompanied by a program of concrete action of a type which does not ask people to voluntarily change the way they live and work—a program which demands little effort or willpower on the part of most people. Such a program would probably have to be a political or legislative one. A philosophy is not likely to make people change their daily behavior, but it might (with luck) induce them to vote for politicians who support a certain program. Casting a vote requires only a casual commitment, not a strenuous application of willpower. So we are left with the question: What kind of legislative program would have a chance of saving freedom?

I can think of only two possibilities that are halfway plausible. The discussion of one of these I will leave until later. The other, and the one that I advocate, is this: In simple terms, stop scientific progress by withdrawing all major sources of research funds. In more detail, begin by withdrawing all or most federal aid to research. If an abrupt withdrawal would cause economic problems, then phase it out as rapidly as is practical. Next, pass legislation to limit or phase out research support by educational institutions which accept public funds. Finally, one would hope to pass legislation prohibiting all large corporations and other large organizations from supporting scientific research. Of course, it would be necessary to eventually bring about similar changes throughout the world, but, being Americans, we must start with the United States; which is just as well, since the United States is the world’s most technologically advanced country. As for economic or other disruption that might be caused by the elimination of scientific progress—this disruption is likely to be much less than that which would be caused by the extremely rapid changes brought on by science itself.

I admit that, in view of the firmly entrenched position of Big Science, it is unlikely that such a legislative program could be enacted. However, I think there is at least some chance that such a program could be put through in stages over a period of years, if one or more active organizations were formed to make the public aware of the probable consequences of continued scientific progress and to push for the appropriate legislation. Even if there is only a small chance of success, I think that chance is worth working for, since the alternative appears to be the loss of all human freedom.

This solution is bound to be attacked as “simplistic.” But this ignores the fundamental question, namely: Is there any better solution or indeed any other solution at all? My personal opinion is that there is no other solution. However, let us not be dogmatic. Maybe there is a better solution. But the point is this: If there is such a solution, no one at present seems to know just what it is. Matters have progressed to the point where we can no longer afford to sit around just waiting for something to turn up. By stopping scientific progress now, or at any rate slowing it drastically, we could at least give ourselves breathing space during which we could attempt to work out another solution, if one is possible.

There is one putative solution the discussion of which I have reserved until now. One might consider enacting some kind of bill of rights designed to protect freedom from technological encroachment. For the following reasons I do not believe that such a solution would be effective.

In the first place, a document which attempted to define our sphere of freedom in a few simple principles would either be too weak to afford real protection, or too strong to be compatible with the functioning of the present society. Thus, a suitable bill of rights would have to be excessively complex, and full of exceptions, qualifications, and delicate compromises. Such a bill would be subject to repeated amendments for the sake of social expedience; and where formal amendment is inconvenient, the document would simply be reinterpreted. Recent decisions of the Supreme Court, whether one approves of them or not, show how much the import of a document can be altered through reinterpretations. Our present Bill of Rights would have been ineffective if there had been in America strong social forces acting against freedom of speech, freedom of worship, etc. Compare what is happening to the right to bear arms, which currently runs counter to basic social trends. Whether you approve or disapprove of that “right” is beside the point—the point is that the constitutional guarantee cannot stand indefinitely against powerful social forces.

If you are an advocate of the bill-of-rights approach to the technology problem, test yourself by attempting to write a sample section on, say, genetic engineering. Just how will you define the term “genetic engineering” and how will you draw the line, in words, between that engineering which is to be permitted and that which is to be prohibited? Your law will either have to be too strong to pass; or so vague that it can be readily reinterpreted as social standards evolve; or excessively complex and detailed. In this last case, the law will not pass as a constitutional amendment, because for practical reasons a law that attempts to deal with such a problem in great detail will have to be relatively easy to change as needs and circumstances change. But then, of course, the law will be changed continually for the sake of social expedience and so will not serve as a barrier to the erosion of freedom.

And who would actually work out the details of such a bill of rights? Undoubtedly, a committee of congressmen, or a commission appointed by the president, or some other group of organization men. They would give us some fine libertarian rhetoric, but they would be unwilling to pay the price of real, substantial freedom—they would not write a bill that would sacrifice any significant amount of the organization’s power.

I have said that a bill of rights would not be able to stand for long against the pressures for science, progress, and improvement. But laws that bring a halt to scientific research would be quite different in this respect. The prestige of science would be broken. With the financial basis gone, few young people would find it practical to enter scientific careers. After, say three decades or so, our society would have ceased to be progress-oriented and the most dangerous of the pressures that currently threaten our freedom would have relaxed. A bill of rights would not bring about this relaxation.

This, by the way, is one reason why the elimination of research merely in a few sensitive areas would be inadequate. As long as science is a large and going concern, there will be the persistent temptation to apply it in new areas; but this pressure would be broken if science were reduced to a minor role.

Let us try to summarize the role of technology in relation to freedom. The principal effect of technology is to increase the power of society collectively. Now, there is a more or less unlimited number of value-judgments that lie before us: for example: whether an individual should or should not have puritanical attitudes toward sex; whether it is better to have rain fall at night or during the day. When society acquires power over such a situation, generally a preponderance of the social forces look upon one or the other of the alternatives as Right. These social forces are then able to use the machinery of society to impose their choice universally; for example, they may mold children so successfully that none ever grows up to have puritanical attitudes toward sex, or they may use weather engineering to guarantee that the rain falls only at night. In this way there is a continual narrowing of the possibilities that exist in the world. The eventual result will be a world in which there is only one system of values. The only way out seems to be to halt the ceaseless extension of society’s power.

I propose that you join me and a few other people to whom I am writing in an attempt to found an organization dedicated to stopping federal aid to scientific research. It would be a mistake, I think, to reject this suggestion out of hand on the basis of some vague dogma such as “knowledge is good” or “science is the hope of man.” Sure, knowledge is good, but how high a price, in terms of freedom, are we going to pay for knowledge? You may be understandably reluctant to join an organization about which you know nothing, but you know as much about it as I do. It hasn’t been started yet. You would be one of the founding members. I claim to have no particular qualifications for trying to start such an organization, and I have no idea how to go about it, I am only making an attempt because no better qualified person has yet done so. I am simply trying to bring together a few highly intelligent and thoughtful people who would be willing to take over the task. I would prefer to drop out of it personally because I am unsuited to that kind of work; in fact I dislike it intensely.

Ship of Fools

Once upon a time, the captain and the mates of a ship grew so vain of their seamanship, so full of hubris and so impressed with themselves, that they went mad. They turned the ship north and sailed until they met with icebergs and dangerous floes, and they kept sailing north into more and more perilous waters, solely in order to give themselves opportunities to perform ever-more-brilliant feats of seamanship.

As the ship reached higher and higher latitudes, the passengers and crew became increasingly uncomfortable. They began quarreling among themselves and complaining of the conditions under which they lived.

“Shiver me timbers,” said an able seaman, “if this ain’t the worst voyage I’ve ever been on. The deck is slick with ice; when I’m on lookout the wind cuts through me jacket like a knife; every time I reef the foresail I blamed-near freeze me fingers; and all I get for it is a miserable five shillings a month!”

“You think you have it bad!” said a lady passenger. “I can’t sleep at night for the cold. Ladies on this ship don’t get as many blankets as the men. It isn’t fair!”

A Mexican sailor chimed in: “¡Chingado! I’m only getting half the wages of the Anglo seamen. We need plenty of food to keep us warm in this climate, and I’m not getting my share; the Anglos get more. And the worst of it is that the mates always give me orders in English instead of Spanish.”

“I have more reason to complain than anybody,” said an American Indian sailor. “If the palefaces hadn’t robbed me of my ancestral lands, I wouldn’t even be on this ship, here among the icebergs and arctic winds. I would just be paddling a canoe on a nice, placid lake. I deserve compensation. At the very least, the captain should let me run a crap game so that I can make some money.”

The bosun spoke up: “Yesterday the first mate called me a ‘fruit’ just because I suck cocks. I have a right to suck cocks without being called names for it!”

It’s not only humans who are mistreated on this ship,” interjected an animal-lover among the passengers, her voice quivering with indignation. “Why, last week I saw the second mate kick the ship’s dog twice!”

One of the passengers was a college professor. Wringing his hands he exclaimed,

“All this is just awful! It’s immoral! It’s racism, sexism, speciesism, homophobia, and exploitation of the working class! It’s discrimination! We must have social justice: Equal wages for the Mexican sailor, higher wages for all sailors, compensation for the Indian, equal blankets for the ladies, a guaranteed right to suck cocks, and no more kicking the dog!”

“Yes, yes!” shouted the passengers. “Aye-aye!” shouted the crew. “It’s discrimination! We have to demand our rights!”

The cabin boy cleared his throat.

“Ahem. You all have good reasons to complain. But it seems to me that what we really have to do is get this ship turned around and headed back south, because if we keep going north we’re sure to be wrecked sooner or later, and then your wages, your blankets, and your right to suck cocks won’t do you any good, because we’ll all drown.”

But no one paid any attention to him, because he was only the cabin boy.

The captain and the mates, from their station on the poop deck, had been watching and listening. Now they smiled and winked at one another, and at a gesture from the captain the third mate came down from the poop deck, sauntered over to where the passengers and crew were gathered, and shouldered his way in amongst them. He put a very serious expression on his face and spoke thusly:

“We officers have to admit that some really inexcusable things have been happening on this ship. We hadn’t realized how bad the situation was until we heard your complaints. We are men of good will and want to do right by you. But — well — the captain is rather conservative and set in his ways, and may have to be prodded a bit before he’ll make any substantial changes. My personal opinion is that if you protest vigorously — but always peacefully and without violating any of the ship’s rules — you would shake the captain out of his inertia and force him to address the problems of which you so justly complain.”

Having said this, the third mate headed back toward the poop deck. As he went, the passengers and crew called after him, “Moderate! Reformer! Goody-liberal! Captain’s stooge!” But they nevertheless did as he said. They gathered in a body before the poop deck, shouted insults at the officers, and demanded their rights: “I want higher wages and better working conditions,” cried the able seaman. “Equal blankets for women,” cried the lady passenger. “I want to receive my orders in Spanish,” cried the Mexican sailor. “I want the right to run a crap game,” cried the Indian sailor. “I don’t want to be called a fruit,” cried the bosun. “No more kicking the dog,” cried the animal lover. “Revolution now,” cried the professor.

The captain and the mates huddled together and conferred for several minutes, winking, nodding and smiling at one another all the while. Then the captain stepped to the front of the poop deck and, with a great show of benevolence, announced that the able seaman’s wages would be raised to six shillings a month; the Mexican sailor’s wages would be raised to two-thirds the wages of an Anglo seaman, and the order to reef the foresail would be given in Spanish; lady passengers would receive one more blanket; the Indian sailor would be allowed to run a crap game on Saturday nights; the bosun wouldn’t be called a fruit as long as he kept his cocksucking strictly private; and the dog wouldn’t be kicked unless he did something really naughty, such as stealing food from the galley.

The passengers and crew celebrated these concessions as a great victory, but the next morning, they were again feeling dissatisfied.

“Six shillings a month is a pittance, and I still freeze me fingers when I reef the foresail,” grumbled the able seaman. “I’m still not getting the same wages as the Anglos, or enough food for this climate,” said the Mexican sailor. “We women still don’t have enough blankets to keep us warm,” said the lady passenger. The other crewmen and passengers voiced similar complaints, and the professor egged them on.

When they were done, the cabin boy spoke up — louder this time so that the others could not easily ignore him:

“It’s really terrible that the dog gets kicked for stealing a bit of bread from the galley, and that women don’t have equal blankets, and that the able seaman gets his fingers frozen; and I don’t see why the bosun shouldn’t suck cocks if he wants to. But look how thick the icebergs are now, and how the wind blows harder and harder! We’ve got to turn this ship back toward the south, because if we keep going north we’ll be wrecked and drowned.”

“Oh yes,” said the bosun, “It’s just so awful that we keep heading north. But why should I have to keep cocksucking in the closet? Why should I be called a fruit? Ain’t I as good as everyone else?”

“Sailing north is terrible,” said the lady passenger. “But don’t you see? That’s exactly why women need more blankets to keep them warm. I demand equal blankets for women now!”

“It’s quite true,” said the professor, “that sailing to the north imposes great hardships on all of us. But changing course toward the south would be unrealistic. You can’t turn back the clock. We must find a mature way of dealing with the situation.”

“Look,” said the cabin boy, “If we let those four madmen up on the poop deck have their way, we’ll all be drowned. If we ever get the ship out of danger, then we can worry about working conditions, blankets for women, and the right to suck cocks. But first we’ve got to get this vessel turned around. If a few of us get together, make a plan, and show some courage, we can save ourselves. It wouldn’t take many of us — six or eight would do. We could charge the poop, chuck those lunatics overboard, and turn the ship to the south.”

The professor elevated his nose and said sternly, “I don’t believe in violence. It’s immoral.”

“It’s unethical ever to use violence,” said the bosun.

“I’m terrified of violence,” said the lady passenger.

The captain and the mates had been watching and listening all the while. At a signal from the captain, the third mate stepped down to the main deck. He went about among the passengers and crew, telling them that there were still many problems on the ship.

“We have made much progress,” he said, “But much remains to be done. Working conditions for the able seaman are still hard, the Mexican still isn’t getting the same wages as the Anglos, the women still don’t have quite as many blankets as the men, the Indian’s Saturday-night crap game is a paltry compensation for his lost lands, it’s unfair to the bosun that he has to keep his cocksucking in the closet, and the dog still gets kicked at times.

“I think the captain needs to be prodded again. It would help if you all would put on another protest — as long as it remains nonviolent.”

As the third mate walked back toward the stern, the passengers and the crew shouted insults after him, but they nevertheless did what he said and gathered in front of the poop deck for another protest. They ranted and raved and brandished their fists, and they even threw a rotten egg at the captain (which he skillfully dodged).

After hearing their complaints, the captain and the mates huddled for a conference, during which they winked and grinned broadly at one another. Then the captain stepped to the front of the poop deck and announced that the able seaman would be given gloves to keep his fingers warm, the Mexican sailor would receive wages equal to three-fourths the wages of an Anglo seaman, the women would receive yet another blanket, the Indian sailor could run a crap game on Saturday and Sunday nights, the bosun would be allowed to suck cocks publicly after dark, and no one could kick the dog without special permission from the captain.

The passengers and crew were ecstatic over this great revolutionary victory, but by the next morning they were again feeling dissatisfied and began grumbling about the same old hardships.

The cabin boy this time was getting angry.

“You damn fools!” he shouted. “Don’t you see what the captain and the mates are doing? They’re keeping you occupied with your trivial grievances about blankets and wages and the dog being kicked so that you won’t think about what is really wrong with this ship — that it’s getting farther and farther to the north and we’re all going to be drowned. If just a few of you would come to your senses, get together, and charge the poop deck, we could turn this ship around and save ourselves. But all you do is whine about petty little issues like working conditions and crap games and the right to suck cocks.”

The passengers and the crew were incensed.

“Petty!!” cried the Mexican, “Do you think it’s reasonable that I get only three-fourths the wages of an Anglo sailor? Is that petty?”

“How can you call my grievance trivial? shouted the bosun. “Don’t you know how humiliating it is to be called a fruit?”

“Kicking the dog is not a ‘petty little issue!’” screamed the animal-lover. “It’s heartless, cruel, and brutal!”

“Alright then,” answered the cabin boy. “These issues are not petty and trivial. Kicking the dog is cruel and brutal and it is humiliating to be called a fruit. But in comparison to our real problem — in comparison to the fact that the ship is still heading north — your grievances are petty and trivial, because if we don’t get this ship turned around soon, we’re all going to drown.”

“Fascist!” said the professor.

“Counterrevolutionary!” said the lady passenger. And all of the passengers and crew chimed in one after another, calling the cabin boy a fascist and a counterrevolutionary. They pushed him away and went back to grumbling about wages, and about blankets for women, and about the right to suck cocks, and about how the dog was treated. The ship kept sailing north, and after a while it was crushed between two icebergs and everyone drowned.

1999 Ted Kaczynski

Selections from Articles

Defending the Unabomber. Mar. 16 1998 The New Yorker

The ending—abrupt, unsatisfying, badly understood—befitted * t&e strange, unhappy saga of Theodore J. Kac -ynski. -le was spared a grueling trial, the judgment of an elaborately chosen death qualified jury, and a strong chance of being condemned t to death, but he was saved from all of this by a bizarre alliance of lawyers he was trying to fire, a family he had renounced, psychiatrists he did not trust or respect (and in some cases had never met ), a federaljudge who had drastically restricted his right to council and seemed to fear (with reason) the trial to come, a press convinced that he was a paranoid schizophrenic, and, finally,, a legendary death penal ty opponent skilled at "client management" (managenment, that is, of Kaczynski), Much of the story took place entirely out of public view. Kaczynski pleaded guilty, in latej January, to all charges, and forswore all appeals, in exchange for a life sentence.. In our overburdendi courts, defendants are often left with little choice but to plead guilty, forfeiting their right tib a trial in exchange for a lesser sentence. But Ted Kaczynski was not just another defendant denied his day in court.

The Manifesto, as it became known, denounced modern technology and u^ged a revolution in the name of Wild Nature. Jefferson Morley, and editor at the Post, described it as "a romantic turgid, disturbing document—but so were the 'Port Huron Statement' (which marked the birth of the new left in 196?') and 'Witness' Whittaker! ChamberJs autobiography In 1952 8 (irktbh marked the birth of the modern right)." Most Americans didn't read it, and considered its author notling more thaA an evil coward.

For six weeks, Kaczynski watched with great interest as his lawyers grilled the prospective jurors. Here were the ordinary technology oppressed Americans in whose name he had conducted his long campaign of terror against "the technOdan class.

...a profound conflict had been growing between Kaczynski a and his lawyers virtually since his arrest. They believed that his best, if not his only, hope of escaping a death sentence was to claim that he was mentally ill. He staunchly refused to do so. This clash of wills and world views eventually erupted into open court. But before he was y ,hhdd offstage, Kaczynski's quietly fierce performance raised fundamental questions about a defendants right to participate in his own defense, the role of psychiatry in the courts, and the pathologi zing of radical dissent both in the courts and the press.

He was a bookbsh, brilliant boy, born in 1942, the first child of ambitious, self-educated parents. Reaped in a working class Chicago suixurb, he skipped two grades, had few friends, liked to shut himself up in his attic room. He was a nerd's nerd, shy and arrogant, socially doomed. For playmates, he was forced to rely on his brother, David, who was seven years younger, popular and easygoing.

At sixteen, Ted had entered Harvard tn a scholarship. He liesd in the Eliot house, where big, swaggering rich boys ruled the roost. Ted, physically slight and badJJ dressed? ate alone.

ihough not a popul ,r teacher (at Berkeley) he continued to publish impressively and was on track for tenure in one of the world's top math departments. Then, in 1969, he suddenly r resigned, telling his family that he wanted didn't want to teach math to engineers who would use i t to harm the environment...

Ted and Davidb bought 1.4 acres together tn Montana, in hign country just west of the continental divide. And that was wher where Ted lived for the next twenty five years. He built a sin simple, ten-foot-by- twelve foot cabin with two small

windows, a woodstove, no electricity, no plumbing. He grew a garden, built a root cellar, hunted rabbits and deer, exchanged vegetables with neighbors, didn't file a federal tax return. He rode an old bicycle five miles Into the town of Lincoln for supplies, and spent a lot of time at the public library there . His parent* visited him there each summer for the first few years.

There was never any doubt that Kaczynski was legally sane. But his lawyers believed that the degree of his culpabillity for his crimes could be made to depend on his psychiatric classification — the more serious.his diagnosis, the less his culpability.

They called him a "high functioning" par mold schizophrenic. Medically speaking, that would place him at the least-ill end of the spectrum of schizophrenia, where the obvious symptoms are often absent. The primary evidence of his illness seemed to be in his writings (most of which have never been made public), in his family's stories, and in his way of life.

Dr. Karen Fromlng, who specializes in neurophychological assessment, gave Kaczynski a battery of tests that "revealed deflcltsx of a mild nature in the areas of frontal and cerebellar motor functions, microsomnia or smell functions,

cognitive processing efficiency, visual memory, and affective processing." Tnese deficits were consonant, she said, with paranoid schizophrenia. They did not, however, prove it. What really indicated such a diagnosis to her, Dr. Froming told me, were Kaczynski's systematized paranoid delusions. I asked wh.t those delusions were.

"Anti-technology," Dr. Froming said simply. "His view of technology as the vehicle by which people are destroying themselves and the world." The Manifesto, in other words....

(Another doctor) Dr. Deitz had, however, read Kaczynski's journals, and h. d not found them to show schizophrenia. "They're full of strong emotions, considerable anger, and an elaborate, closely reasoned system of belief about the adverse impact of technology on society. The

question always is: /s that belief system philosophy or is it delusion? The answer h is more to do with the ideology of the psychiatrist than with anything else."

Kaczynski's own ideology give psychiatrists short shrift. "The concept of 'mental health' in our society is defined largely by the extent to which an individual behaves in accord with the needs bf the (industriii - technological) system and does so without showing signs of stress."

In his journals, he recorded his fear that his campaign againsi industrial society would ultimately be dismissed as the work o Of A

"sickle," observing that, "many time, conformist have a powerful need to depict the enemy of soci society a8 sordiri

• repulsive, or sick.?" He noted the old

Soviet practice of supressing

dissidents by labelling them mentally ill.

...its real implications are more disturbing still, for it suggests what few of us like to acknowledge — that sane, rational people may commit vilent, terrible acts, including serial murder.

Ted Kaczynski, in his refusal to plead mental Illness, was not only refusing to recant his ideas, but also refusing to recant his acts. He had done what he had done for the reasons he had given. And he was apparently prepared to explain those reasons to the jury and the world. He even hid, virtually from the beginning, a lawyer who was ready and well qualified to step in and help him make his deeplv subversive case.

J. To"y Serra had gotten in touch with Kaczynski shortly after his arrest. Serra was the real-life inspiration for a 1989 film, "True Believer," starring James Woods, about a flamboyant radical attorney who defends unpopular clients. Known f<">r courtrooms eloquence, a long,grey ponytail, Salistion Army suits, and a marijuana habit, Serra has built an enviable record of legal victor es, often in cases that other lawyers wouldn't touch. He has represented Black Panthers, White Panthers, members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, He has twice won freedom for men already condemned to death in California. He works pro-bono much of the time, and that was what he proposed to do for Kaczynski. He has, he says, the highest regard for public defenders, who, like him, spend their careers representing the poor and the despised.." j reppect them and T love them,',' he tolld me. "They are my allies But Kaczynski's lawyers were intent on saving his life Wfth a defense th.it their client did not want. "I am of a different ilk," Serra told me. "I have always servdd the objective of the client. A person has the right to defend himself in the manner he ch< .3, even if it means death, as long as he appreciates tne risk. Kaczynski appreciated and understood all the ramifications and wanted a trial based on an ideological defense."

As Serra envisioned such a defense—wwhich could probably be argued only during the penalty phase of the trial — Kaczynski would explain himself to the jury, using the Manifesto. Eminent poi-'teal scientists would be calle to interpret the essay, paragraph by paragraph. The defense case would be based on what Serra called rimperfect necessityu- you commit a crime to avert a greater disaster that you believe will occur," though others may find your belief unreasonable. :lt doesn't eliminate culpability," Serra noted, but it lowers culpability." Serra was confident that

Kaczynski's case against technology would be

Perfectly comprehensible to the jurors. "It's not crazy, and not difficult to understand. And if the hole in the k opens up and kills us all, he'll be proved right!"

’ who h ,s represented his share of disturbed

’ did not consider Kaczynski mad. Indeed, he told a repotter, ”Thi h a-

guy ig a genius. He sees things we

can't see and understands things we can't understand.

Maybe we should give him the benefit of the doubt."

Scharlette Holdman, a veteran death-penalty "mitigation investigator" had been described to me by a

former colleague as a specialist in "client management," and she spent many hours a week with Kaczynski during the long months of trial preparation. She was one of the links between Kaczynski and the outside world, which included his political, supporters—an amorphous but vivid crew of anarchists and enviro-radicals, who gathered primarily on the indernet. Holdman even persuaded key figures in that world to shut down their support campaigns as the trial approached, lest they disrupt delicate plea negotiations. Holdman's councils to Kaczynski himself hive not been disclosed, but he was obviously kept firmly in the dark for as long as possible about the extent of his teams plansto depict him at trial as mentally ill. . ....

Kaczynski was evidently not seeing much of the press coverage of hi s case, where his lawyers plan to offer a "mental defect" defense was being reported. Indeed it was only in the second half of November, with the jury selection well under way, that Kaczynski discovered that his lawyers were planning to introduce testimony from the

psychiatrists who had diagnosed his condition as piranold schizophrenic. He w is furious, and protested vehemently. And that was when, with the trial itself rapidly approaching, a game of legal chicken began. In Scharlette Holdman's experience,

It was the client who normally flinched in these situations. This client did not flinch.