Various

Newsweek's Unabomber Issue

Chasing the Unabomber

Terror: A portrait of the murderous serial bomber emerges as he lunges for publicity, tweaks the FBI—and remains very much on the lam after 17 years of bizarre attacks

It has all the elements of a summer box-office smash-a campy thriller about a crazed criminal mastermind who holds the great city in fear. But this was Los Angeles, not Hollywood. The reality last week was that LAX, the nation's third busiest airport, was tied up in knots at the onset of the summer travel season while a team of frustrated FBI agents vainly chased the phantom who has eluded them for 17 years. Batman didn't show, nor did Bruce Willis--and finally, the murderer known as Unabomer revealed his little joke. "Since the public has a short memory, we decided to play one last prank to remind them who we are," Unabomer announced in a typically coy letter to The New York Times. "But no, we haven't tried to plant a bomb on an airliner recently."

Great-just what America needs, a serial killer with a macabre sense of humor. Worse, this murderer (three dead and 23 injured since 1978) appears to have an insatiable appetite for recognition and enough brains to give OKBomb suspect Tim McVeigh a run for his money in the alleged-bomber-of-the-year competition. That, in all probability, is what last week's caper was about. It was a publicity ploy designed to wrest the spotlight of national-news attention away from McVeigh and bring it back to the humble craftsman who, as he told us in April, spends "all [his] evenings and weekends preparing dangerous mixtures, filing trigger mechanisms out of scraps of metal [and] searching the sierras for a place isolated enough to test a bomb." Make no mistake: though he denies it, the Unabomer now has an epic case of envy that began with Oklahoma City.

He still has a long way to go, for with 168 victims, the OKBomb perps still easily hold the U.S. record for slaughtering innocents with homemade devices. Still, the Unabomer is putting on a rare show for psychologists and other behavioral scientists, some of whom are clearly impressed by his combination of intellect, malice and showmanship. He has arguably raised murder by mail to the level of performance art. And as he promised in April, the bomber has now produced a grandiose message that seems intended to explain his homicidal career. This personal and political manifesto, 35,000 words long, was mailed last week to The New York Times, The Washington Post and Bob Guccione, publisher of Penthouse magazine. (It was not sent to NEWSWEEK, as the Unabomer announced in April.) The document was accompanied by a demand for publication in exchange for the bomber's solemn vow not to kill anyone else. But there were a few caveats. The killer refused to give up bombing property, and he demanded that the papers publish three annual follow-up statements he intends to write. He also reserved the fight, if that is the word, to kill one more person if his proclamation appeared in Penthouse instead of one of the "respectable" publications. The 85,000-word statement, not yet released by its recipients,gives the FBI its best look so far at the inner workings of the Unabomer's mind, and may provide the clue that brings him down.

As described in the Times, the manifesto was mostly about technology--like computers and genetic engineering--and the social and environmental change they are bringing to the world. Unabomer doesn't like science and technology--he says they are "permanently reducing human beings and many other living organisms to engineered products and mere cogs in the social machine." He advocates "revolution against the industrial system" and a return to "wild nature."

The newspapers and Guccione must now decide whether to accede to Unabomer's demand in the hope of saving lives, or whether negotiating with a madman might do more harm than good (page 46). In the meantime, however, the Unabomer has achieved precisely what he wanted, which was to "meet" some of the most powerful publishing figures in the country on roughly equal terms.

His disdain for lawful authority needs no demonstration. In April, after the bombing death of Gilbert Murray, chief lobbyist for the California Forestry Association, Unabomer called the FBI "a joke." He has tempered his language a bit, but his contempt still runs strong. "For an organization that pretends to be the world's greatest law-enforcement," he wrote the Times, "the FBI seems surprisingly incompetent." There was another bit of sly humor in the letter announcing his bomb threat. This missive, sent to the San Francisco Chronicle, listed "Frederick Benjamin Isaac Wood" as the return addressee. Wood is one of Unabomer's trademarks: he uses it as a bomb component and frequently invents woody-sounding names and addresses for his lethal packages. So "F.B.I. Wood" was another little joke.

What is one to make of a man who is an anonymous egomaniac, a self-taught machinist who hates all technology, and a killer whose professed goal is to live in harmony with nature? Obviously, the Unabomer is no ordinary bad guy, which is why the FBI and other law-enforcement agencies have had so much trouble tracking him down (page 44). Criminals--even career criminals--are typically none too smart, and many are eventually tripped up by their own M.O.s. But Unabomer has continually changed and improved both his bombs and his tactics-which suggests that, educated or not, he is very intelligent. He is also not insane in the usual sense of the word. He is clearly in touch with everyday reality, and he has been able to maintain his cover for an extremely long time. So while Unabomer probably fits the "quiet loner" stereotype, and while some experts think he may have problems with women, he does not appear to be a serial killer in the mold of Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy or Jeffrey Dahmer. He is not, from the available evidence, a sexually driven psychopath.

His mainspring--the apparent reason for it all--is vanity or narcissism. Consider the power trip inherent in watching the FBI chase its taft, or watching authorities at LAX (and other California airports) get the shakes. Consider the ego rush in seeing prestige publications like the Times and the Post, which owns NEWSWEEK, forced to take his views seriously. "He's enjoying it to the max--trying to jack us around, taunting and teasing the media and the public," says San Francisco State University criminologist Michael Rustigan. "The guy's not getting tired, he's in his prime. He was a fledgling author, now he's in the big leagues. He's not small fry, cutting his wood and perfecting the layers of metal in his basement in northern California. He's Serial Bomber No. 1, he's stopped the nation, he's graduated."

NEWSWEEK has obtained two new pieces of evidence about the Unabomer. One is a letter he claims to have sent to the San Francisco Examiner in 1985, after one of his devices crippled John Hauser, a graduate student of the University of California, Berkeley. This letter, a copy of which was sent to Guccione, is an early and much shorter version of the Unabomer manifesto. Although the FBI believes he has always worked alone, the bomber claims to be a terrorist group calling itself "the Freedom Club." That name appears to answer the question of why virtually all his bombs contain at least one metal part carefully stamped with the letters "FC--a "signature" designed to be retrieved after the bomb explodes. The letter attacks "the old revolutionary ideologies" and says the Freedom Club "is strictly anti-communist, anti-socialist, anti-leftist." But the writer also says "this does not imply that we are in any sense a right-wing movement. We are apolitical. Politics only distracts attention from the real issue," which is science, technology, the complexity of modern society and the rule of elites.

The second piece of evidence is a letter sent to Scientific American magazine last week. The letter also claims to be a message from the terrorist group FC, and it is essentially a diatribe against the "arrogance" of modern science. "Scientists and engineers constantly gamble with human welfare," the writer says, "and we see today the effect of some of their lost gambles--ozone depletion, the greenhouse effect, cancer-causing chemicals. . .overcrowding, noise and pollution [and the] massive extinction of species .... "Significantly, the letter also says "we strongly deplore the kind of indiscriminate slaughter that occurred in the Oklahoma City event," another indication that OKBomb has wounded his pride.

Taken as a group, the "FC" letters are alternately preachy, chatty, ironic and even subtly serf-mocking. They are surely the most remarkable letters any serial killer ever wrote, and they seem to indicate the bomber's need to justify his actions. Earth First!, a radical environmental group, recently denounced his form of terrorism, and some anarchists have similarly distanced themselves. Nevertheless, the Unabomer in his letter to The New York Times makes violence seem almost reasonable: how else, he says, could he get his Luddite views considered by major news organizations? He also admits error when he tried to bomb an American Airlines jet in 1979 (the device did not explode). "The idea was to kill a lot of business people," he wrote. "But of course some of the passengers likely would have been innocent people-maybe kids, or some working stiff going to see his sick grandmother. We're glad now that attempt failed."

He's all heart. The question now is whether the sudden flurry of communications signals some sort of inner crisis that could lead to a mistake--or whether the jokester, always sly, keeps right on killing.

Tom Morgenthau with Gregory Beals in New York, Nadine Joseph in San Francisco, Melinda Liu in Washington and bureau reports.

Tracking an Elusive Killer

Using the mail and choosing hard-to-connect targets, the Unabomer has struck 16 times in 17 years, killing three and maiming 23 in a campaign of terror directed at airlines and techno-industries.

1 May 25, 1978 Northwestern Univ. Evanston, III.

A package returned to the school explodes, injuring a guard

2 May 9, 1979 Northwestern Univ.

A bomb left in the university's Technological Institute injures a student

3. Nov. 15, 1979 American Airlines Flight 444, Chicago to Washington, D.C.

A bomb ignites in the hold of a 727. After the plane's emergency landing, 12 are treated for smoke inhalation

4 June 10, 1980 Lake Forest, III.

United Airlines president Percy Wood is wounded by a bomb mailed to his home.

5 Oct. 1981 Univ. of Utah, Salt Lake City

The police defuse a bomb found by a maintenance worker

6 May 5, 1982 Vanderbilt Univ. Nashville, Tenn.

A wooden box explodes and injures secretary Janet Smith as she opens it

7 July 2, 1982 Univ. of California, Berkeley

Engineering professor Diogenes Angelakos picks up a cylinder thinking it is a student project, and is injured

8 May 15, 1985 Univ. of California, Berkeley

John Hauser is injured when a metal box on a lab counter explodes as he opens it

9 June 13, 1985 Boeing Co., Auburn, Wash.

A package mailed to the Boeing fabrication division on May 8 is safely disarmed

10 Nov. 15, 1985 Ann Arbor, Mich.

A package mailed to psychology professor James McConnell injures his assistant

11 Dec. 11, 1985 Sacramento, Calif.

A bomb hidden in a paper bag kills Hugh Scrutton behind his computer store

12 Feb. 20, 1987 Salt Lake City, Utah

A bomb disguised as two-by-fours explode when kicked by computer store owner

13 June 22, 1993 Tiburon, Calif.

A padded mailer injures Charles Epstein, a geneticist at UCSF

14 June 24, 1993 Yale Univ. New Haven, Conn.

Computer-science professor David Gelernter is disfigured by a bomb at his office

15 Dec. 10, 1994 North Caldwell, N.J.

Advertising executive Thomas Mosser is killed at his home

16 April 24, 1995 Sacramento, Calif.

Taimber-industry lobbyist Gilbert Murray is killed by a bomb at the California Forestry Association

17 June 20, 1995 Los Angeles, Calif.

A bomb threat slows traffic at Los Angeles International Airport

Flummoxing The Feds

As the longtime chief of the FBI's elite explosives unit, Christopher Ronay may know the Unabomer better than anyone else. On the Formica counters of the FBI's brightly lit Washington labs over the years, Ronay has pieced together the terrorist's bombs, admired their growing sophistication and felt a rush of recognition each time he has come across the trademark initials "FC." It was Ronay, then a young lab examiner, who noticed that a partially detonated device aboard an American Airlines jet in 1979 was remarkably similar to two primitive bombs found at Northwestern University months before-and first realized the FBI should be looking for a serial bomber. Since then, two generations of FBI agents have tried to crack the case, "It's been a roller-coaster ride," says Ronay. "Every once in a while, you get that thrill, then you go down that hill again." His own great frustration was retiring last year--no closer, really, to capturing his nemesis than he was all those years ago.

The way things are going, Ronay's successors may retire frustrated, too. The hunt for the elusive Unabomer, after all, has spanned parts of three decades. and cost an estimated $50 million. Investigators from three federal agencies, plus hundreds of state and local police, have pursued thousands of leads at 16 different crime scenes from Connecticut to California. They have offered a $1 million reward and trawled for tips on the Internet. But by last week, they still had few solid clues. At the Unabom task-force headquarters in San Francisco, where more than 80 agents were working out of a federal building office, there was a palpable sense of panic. "The worst part is you have this sword of Damocles over your head the whole time," said one veteran. "Can we catch him before he strikes again?"

Why is the case so tough? Partly because the Unabomer covers his tracks as meticulously as he crafts his bombs. None of his 16 devices has contained a single identifiable fingerprint, hair strand or clothing fiber. He uses no electronic parts that might be traceable. He also shrewdly avoids contact with postal clerks; the eight bombs he sent through the mail were plastered with regular postage stamps-not metered. He always types his addresses on white gummed mailing labels. And he probably doesn't lick them; technicians have found no traces of saliva that might yield a DNA match. He has left a few tantalizing tidbits for Feds to chase, but they've been dead ends. He uses a nine-digit code on his letters so authorities will know they are authentic, but the number-a potential gold mine for FBI cryptographers-turned out to be the social-security number of a recent parolee from a California prison with no apparent connection to the case. One 1998 letter also carried the barely perceptible imprint era handwritten message: "Call Nathan R Wed 7 pm." Canvassing driver's license records and phone books, FBI agents located 10,000 "Nathan R"s nationwide, and questioned many of them--all to no avail.

If anything, the task force has been stymied by too many leads that fit no discernible pattern. When a professor is hit, the Feds compile elaborate computer databases on every former student and every faculty colleague. Those names are then cross-referenced for geographic locations, technical specialties and other possible connections. The early American Airlines explosion prompted exhaustive reviews of thousands of airline employees; the bomb sent to a New Jersey ad executive last year had the Feds scrambling for names of his agency's clients and their employees. The result, said one law-enforcement official still active in the case, "is more leads than you can believe. You start to look at everyone and think he might be a suspect."

The investigation has evolved along with the Unabomer's tactics. "He started out modestly, and so did we," says retired FBI criminal proflier Richard Ault. The bureau initially dubbed him the Junkyard Bomber, because he used odds and ends of pipe, metal and wood in his early devices. Similar fragments turned up in several other crude bombs that exploded in university settings in the 1980s (chart). The FBI's behavioral experts began compiling a criminal profile, and it was elevated to a "major case." At one point, recalls Ault, "some guy poked his head in and said, 'Now it's called UNABOM' "(because the victims had been at universities and airlines).

Then the Unabomer laid low for three years. He knew his early devices had been "embarrassingly ineffectual," and he wanted to learn more about explosives, he explained in a letter he claimed to write in 1985 that surfaced last week. When he suddenly struck again, his bombs were more sophisticated--but his targets still seemed indiscriminate. John Hauser, an aspiring astronaut and an engineering student, happened to open a metal box left in a computer room at Berkeley. The blast blew off his fingers and flung his Air Force Academy ring so hard that it left an imprint of the word ACADEMY on the wall.

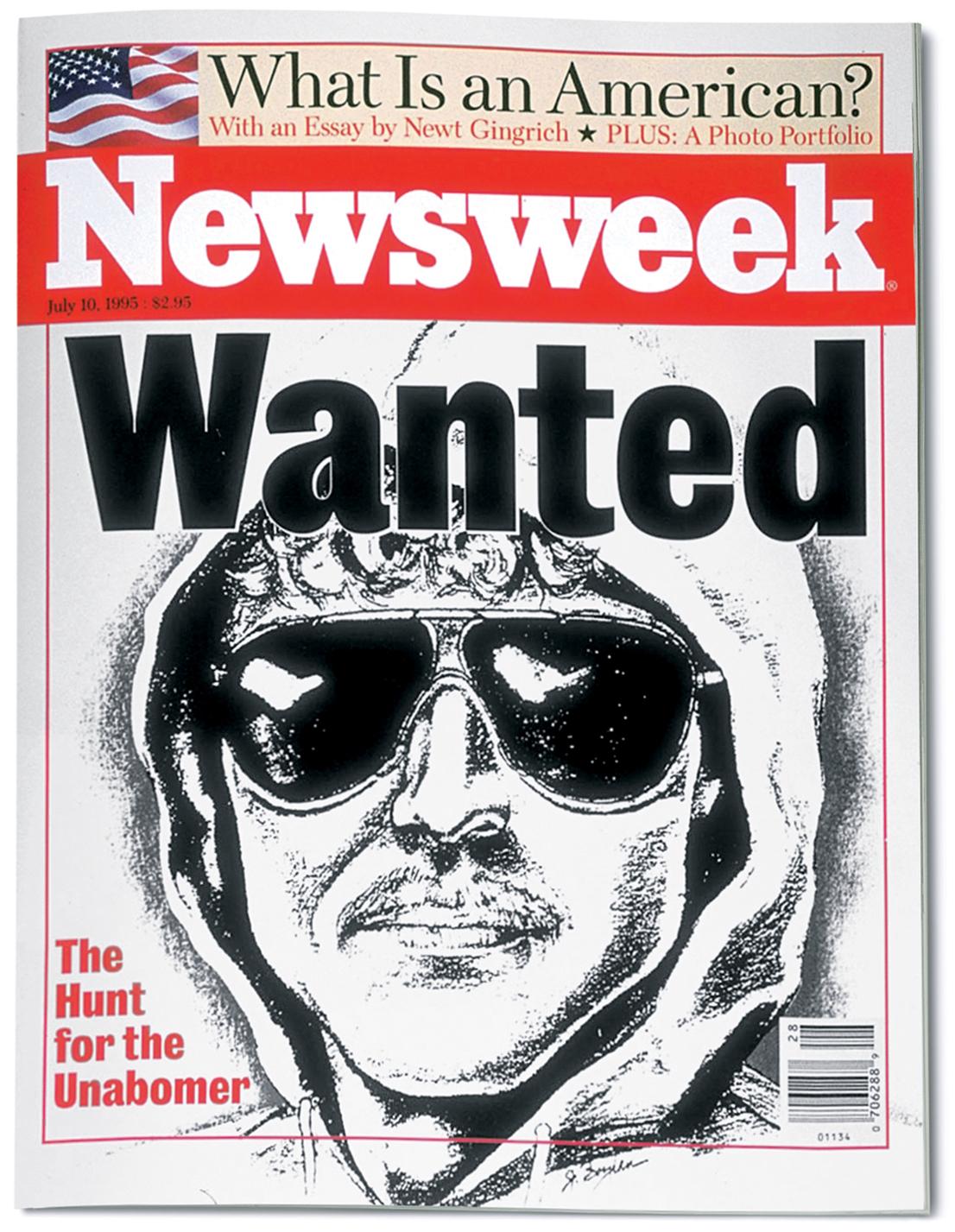

The only real break to date came by accident. In Salt Lake City, in 1987, a woman looking through a window spotted a white man in a hooded sweat shirt and sunglasses carrying a jumble of wooden boards in a laundry bag. She watched as he set it down in a parking space-and she banged on the window, motioning for him to move it. He looked at her, and calmly walked away. Less than an hour later, computer-store owner Gary Wright was injured as he knelt beside the contraption--and within hours, the FBI had a composite sketch of Unabomer.

Agents streamed into Salt Lake City. "I think we came very close--we may have interviewed him," recalls retired agent Lou Bertram. But after several months, the leads petered out--and for six years, so did the bombings. Agents speculated that Unabomer might have been arrested on another charge, been admitted to a psychiatric ward--or just gotten spooked. The task force was largely shut down.

Then came 1998. That spring, the bureau was reeling from the World Trade Center bombing and the fiery inferno at Waco. Within three days in June, Unabomer sent mail bombs to a geneticist in San Francisco and a computer scientist at Yale. The dormant investigation sprang back to life, fueled, too, by a Unabomer letter to The New York Times outlining his political philosophy. The task force regrouped in San Francisco; retired agents were called back in as consultants. Authorities fine-tuned and re-circulated the old composite sketch--though he almost surely looks different now. And to raise the stakes even higher, he became more deadly. The bomb he mailed to ad executive Thomas Mosser last December killed him instantly. The one he sent in April not only killed timber lobbyist Gilbert Murray, it wrecked his entire office.

At this point, investigators only hope that Unabomer continues mailing manuscripts, not munitions. After 17 years in the shadows, he's showing signs of the trait most serial killers develop: the "urge to purge," as Ault puts it. "He's human and he has to talk to someone and that could give him away." Then again, the Unabomer has always confounded expectations. "He's probably watching television and laughing to himself, saying, 'You sons of guns. For 17 years, you've been trying to figure me out'," says retired agent Peter Smerick, who helped develop Unabomer profiles at Quantico. "You couldn't figure me out then, and you can't figure me out now."

Melinda Beck with Michael Isikoff and Melinda Liu in Washington, Gregory Beals in New York, Andrew Murr and Nadine Joseph in California and Karen Springen in Chicago.

Will It Be Publish--or Perish?

Faced with the Unabomber, journalists should stall and do what is practical

Jonathan Alter

All the talking heads last week sounded as if ultimatums from terrorists in the United States were a brand-new problem. But turn back the clock a bit. In September 1976, New York-based Croatian separatists hijacked a New York-to-Chicago TWA flight, left a bomb in a locker in Grand Central Station (which killed a police officer) and warned that a second bomb, planted "somewhere in the United States," would be set off unless five major American newspapers printed a propaganda statement in full. What happened? The hijacking ended with the surrender of the terrorists and release of the passengers in Paris. Meanwhile, all five newspapers--including The New York Times and The Washington Post--had printed the 3,500-word manifesto. Benjamin C. Bradlee, then executive editor of the Post, published the statement (in agate type) over the objections of some who argued that it would prompt a lot of copycats to demand space in the paper. It didn't. In the ensuing 19 years, Bradlee says, "we didn't get a single call."

Until now. As the Times and the Post face a similar dilemma over how to handle the much longer statement mailed to them by the Unabomer, all the old issues about handling terrorism are being revisited, only this time it's the media -- not the government -- that have to confront them. "Never negotiate with terrorists" sounds good as a policy. But it's in the same league as "Never sit with your back to the door or eat at a place called 'Mom's'." In the real world, "Mom's" always seems to be the only place open. Even when the Israelis face terrorism, there's always some negotiation; the only question is how much.

The Times and Post do have some options, but most of them are bad. If they hold fast and refuse to publish the theories of this twisted neo-Luddite, then they may have to explain later why they didn't do more to prevent bloodshed. On the other hand, the Unabomer is also demanding three annual follow-up stories. And even then, he hasn't promised to stop blowing up property, much less turn himself in. Where would capitulation lead? The man, after all, is a meticulous self-promoter. He sent the letters specifically to Warren Hoge at the Times and Michael Getler at the Post--both highly placed editors. (In the latter case it sat in Getler's in-box for a day because his secretary was away.) If the newspapers aren't careful, soon he'll start trying to bargain for a better sketch artist or a bigger byline.

Fortunately, the self-styled anarchist gave the newspapers three months to make their decision. Considering that he has been at large for 17 years, he isn't likely to be caught by then. But it gives the press some time to stall and think. One possible solution would be to publish a portion of the statement (the complete text of which would consume seven full newspaper pages) and put the rest of it online. It isn't hard to predict what the Unabomer's reaction to that would be. He apparently monitors the Internet, but his whole philosophy is anti-technology, and his views online would be unavailable to the very computer-poor masses he is apparently trying to whip up into a revolutionary fervor.

Maybe the papers should simply handle the whole thing exactly as the FBI recommends, which is unclear right now. To journalists, this sounds a bit peculiar. A belief has grown up-within journalism and without-that self-respecting publications don't let someone else tell them what to publish. But actually there's a long tradition in the news business of cooperating with authorities when lives are clearly at stake. (It's when reputations are at stake, not lives, that the press usually goes ahead and publishes in defiance of the government.) In his forthcoming memoirs, Bradlee relates several eases of the Post's holding back, in-eluding one story he decided not to run about how American POWs in Vietnam were secretly communicating in photos taken by their captors. NEWSWEEK held off reporting some details about the American hostages in Iran during the Carter administration, among other stories.

But actually turning over space or air time is worse, isn't it? Maybe not. One news chief with a reputation as a tough guy, Don Hewitt, executive producer of CBS's "60 Minutes," says: "I'd ask the head of the FBI if airing it would make us a safer country. If so, I'd do it." And if that led to "60 Minutes" routinely being taken over by terrorists? On second thought, says Hewitt, "It's obviously [CBS chief Larry] Tisch's decision to make." As it happens, even in TV, the copycat problem is not serious. Every so often a gunman will break into a local TV newsroom to demand that a statement be read on the air. It doesn't tend to spawn imitators in that market.

Perhaps the best approach is to simply look at the Unabomer's statement for its journalistic worth and run excerpts. The Times described the statement as "closely reasoned," which is a better review than many authors receive in that paper. Whoever he is, this man is dearly expressing an anger at the modern world that is not only well-articulated but representative of the anxieties of lots of other people. "Tell him to write it good," advises Jimmy Breslin. "If you don't like it, send it back for a rewrite."

Of course, the press gets manipulated often--by politicians, business executives, criminals. Yet even the best writing doesn't get reprinted at 35,000 words in major newspapers, and the Unabomer's prose is hardly deathless. If he made a firm and convincing offer to turn himself in, then it would be worth striking a deal. But short of that, he is simply yanking some mighty heavy chains. The press should keep the lines of communication open, even publish something, but avoid being completely co-opted by a killer.