Warcry

Corresponding with Timothy McVeigh

Terrorist (adjective or noun): The systematic use of terror especially as a means of coercion; characteristic of someone who employs terrorism as a political weapon.

Only weeks before Timothy McVeigh’s execution (which he referred to as “state-assisted suicide”), I wrote him a letter titled “Truth and Execution Strategy.” I had read an essay McVeigh wrote in 1998, which discussed the legacy of brutality in US foreign policy as well as the double standards in society, which enabled and even applauded such aggression.

Remember Dresden? How about Hanoi? Tripoli? Baghdad? What about the big ones—Hiroshima and Nagasaki? At these two locations, the US killed at least 150,000 non-combatants in the blink of an eye. Thousands more took hours, days, weeks or months to die. (T. McVeigh, June 1998, Media Bypass magazine)

Being a student of International Relations, I knew McVeigh was pointing out the obvious. He had an accurate analysis of US capacity to inflict damage on a vastly more devastating scale than most other nations. As the world’s pre-eminent superpower, this nation has the most advanced weaponry and has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to use it indiscriminately.

I asked McVeigh if he would be willing to extend a similar acknowledgment to the “non-combatants” he killed in Oklahoma City. In my letter, I pointed out the contradiction of hating the government, and yet mirroring its disregard for human life. Whether we like it or not, McVeigh’s “propaganda of the deed” set a historical precedent. A clarification from him recognizing the wrong of targeting civilians might prevent would be imitators from taking lives in the future. Furthermore, the state consolidated its defenses as a result of Oklahoma City and only grew stronger. After the bombing, the government passed reams of anti-terrorist legislation.

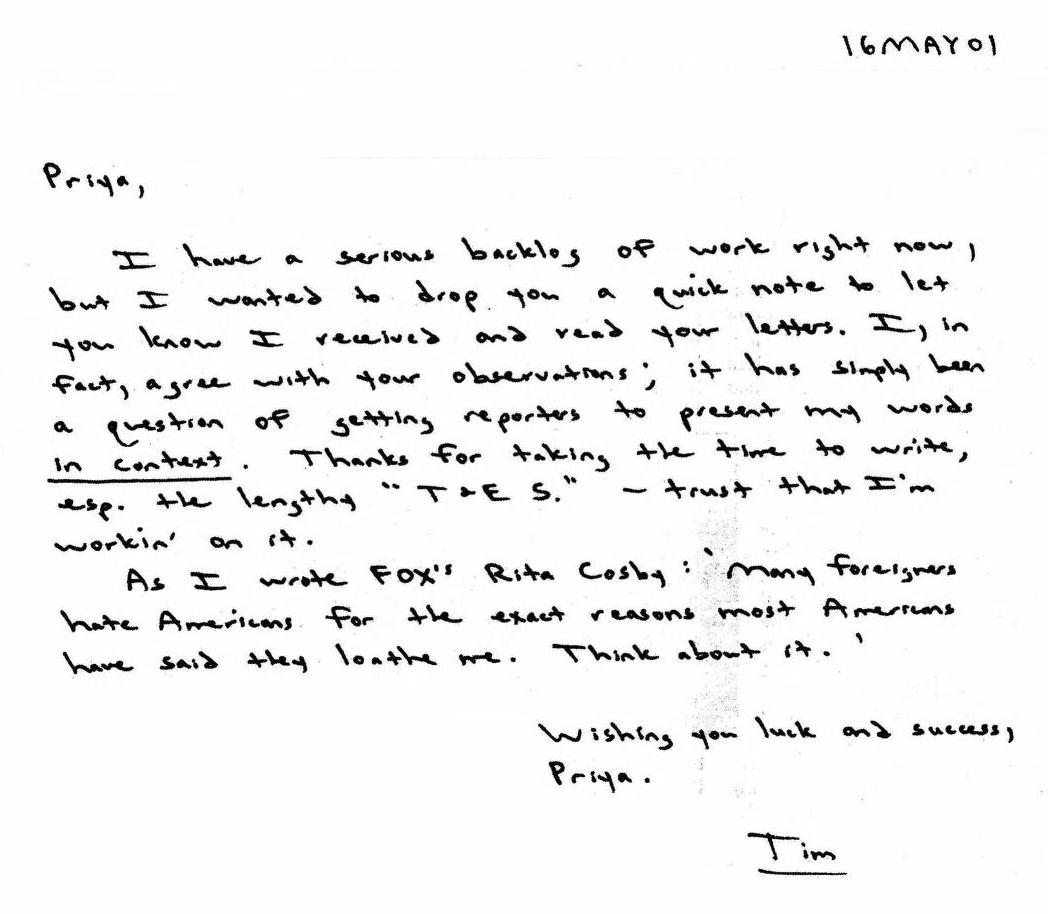

At his sentencing, McVeigh quoted US Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis, “Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or ill, it teaches the whole people by its example.” I wrote McVeigh that, “Napalm and nuclear weapons are pretty good examples of what the government teaches. Your use of the phrases—body count, collateral damage, etc. in your interviews, indicate exactly which lessons you’ve learned. We put the Germans on trial in Nuremberg after World War II, but who put the US on trial for the five million people killed in Southeast Asia, or the millions of Native Americans and Africans that were killed here? This continent was soaked in blood long before you came along, Tim.” He responded to me by saying, “I, in fact, agree with your observations.”

Aside from US bombing victims, more than a million people have been killed in Iraq as a result of the US sanctions alone, according to a 1996 UNICEF report. Former Secretary of State Madeleine Alright, when questioned in a 60 minutes interview specifically about the dying Iraqi children, responded “we think the price is worth it.”

Do people think that government workers in Iraq are any less human than those in Oklahoma City? That Iraqis don’t have families who will grieve and mourn the loss of their loved ones? Do people come to believe that the killing of foreigners is somehow different than the killing of Americans? (T. McVeigh, June 1998, Media Bypass magazine)

When I mention that Tim McVeigh wrote to me, people sometimes act offended. Would they be equally repelled if Henry Kissinger or Madeline Albright had written to me instead? Both of whom are responsible for a far greater “body count” than McVeigh. Some dismiss McVeigh’s critique, because he had been linked to white supremacist groups. I’ve never heard McVeigh advocate racist ideas, however I have heard him discuss government misconduct at length. I can only conclude that the former is far less important to him than the latter. My purpose is not to excuse anything about McVeigh—but rather, to put his terrorism into a useful perspective for social analysis.

This country condemned McVeigh and cut him off like a cancer without recognizing that the whole body politic was diseased. If McVeigh was a monster, it’s because this system needs and creates monsters. We know he was responsible for tremendous horror in Oklahoma City, but who is responsible for Timothy McVeigh?

“I wanted to see more of the world. I had never really gotten out of my hometown. I fell for the sales slogans: ‘Be all you can be’ and, ‘We do more before nine o’clock than most people do in a day.’ I said, alright, let’s try it.” (McVeigh interview with Time magazine)

McVeigh was a decorated veteran of the Persian Gulf War, which he referred to “as getting medals for killing people.” As a soldier, he recognized Waco as an act of war on the American people, and he reacted the way he was trained to, violently. When I had read that he was submitting the poem Invictus by William Henley as his final statement, I wrote saying that “such a dramatic exit wasn’t going to be enough.” I encouraged McVeigh to use the attention around his execution to attack US foreign policy and the massive social hypocrisies that legitimize government criminality. I didn’t want McVeigh to squander the world’s attention with a melodramatic poem that according to USA today, “rebellious teenagers give to their parents.” I suggested that he “highlight the actions of the most powerful terrorist on the block, by contextualizing his atrocity with those committed by the state.” In my response to his letter, I described to McVeigh a short antiwar punk rock music video I had just completed which uses Vietnam war era footage. It is a gruesome but truthful history lesson for the kids who would see it.

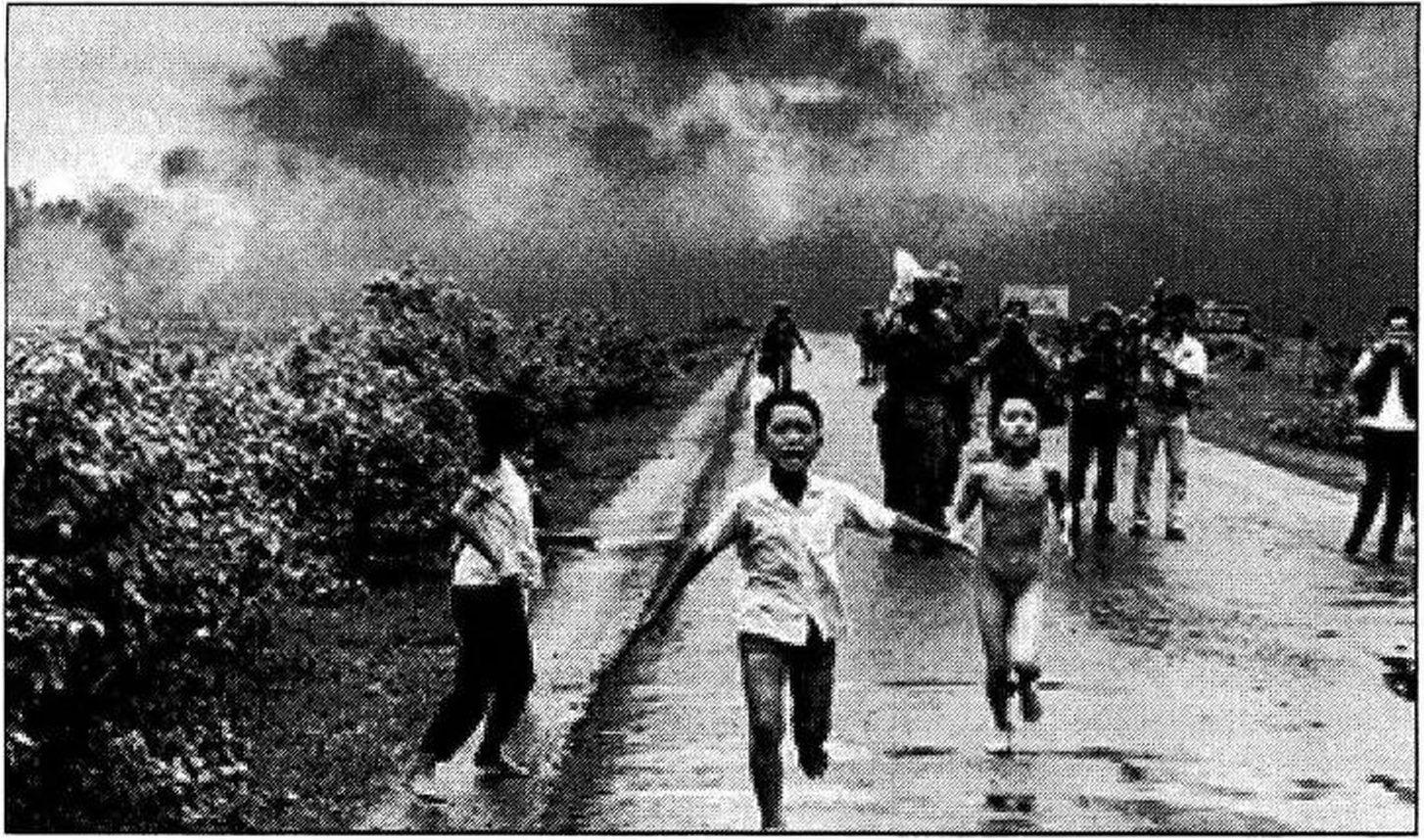

No matter what Mcveigh said, his words would be overwhelmed by the bloodiness of his actions. Maybe that’s why he chose to say nothing. The day McVeigh died, I received an envelope from him in the afternoon mail. In his final hours, he had forwarded to me a letter from a 77 year-old man who wanted to start an anti-war group in Arizona called “War No More” and wanted McVeigh to describe his experiences as a soldier in the hopes of teaching school kids about the consequences of war. Enclosed with the letter was the famous photo of the little Vietnamese girl who had been napalmed and was running down a road with her brother— their faces full of agony. Exactly what my video was about. Maybe my video could be of use. Why did he fail to assert the issues and criticisms he raised in his essays and interviews in front of an attentive world? What the hell can I do about it now? I was really disappointed that he hadn’t said anything useful about this entire tragedy. What a waste of 168 lives and now 169.

That evening, Tom Brokaw referred to the execution as “McVeigh’s twisted legacy” and encouraged viewers to “keep faith in the law.” President Bush addressed the matter as “concluded.” The only follow up reporting was on the tumultuous feelings of the bombing survivors, and details such as McVeigh’s last meal and how quickly the lethal injection worked.

Terre Haute, Indiana, where McVeigh died, is French for “high ground”— ironic in a situation where no moral high ground is available for this nation. McVeigh’s last words to me were, “Most foreigners hate Americans for the exact reasons most Americans have said they loathe me. Think about it.”

The only thing out of the ordinary about Tim McVeigh was that he launched an act of pure tactical aggression on US soil. McVeigh was a terrorist because he used terror for political ends, but by that definition, he’s hardly the only one.

All those here share a single penalty for the same fault. He said no more.

Inferno VI/Dante