What Does She See in Him? Hybristophiles and Spree Killers

Spree Killings and Spree Killers

The Value of Adding Evolutionary Frameworks for Understanding Behavior

Online Communities—The Social Context of Parasocial Relationships

Celebrity Culture and Individual Personality

Data Collection: Context of the Fanbase for Spree Killers

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: Variables 1–23

Cluster Profiles: Variables 1–23

Abstract

For further understanding of spree killers, we explored fan communities of the same on Tumblr. We aimed to fit their expressed paraphilic desires with earlier typologies of aggressive/passive hybristophiles (women who fetishize killers) and a previously proposed typology of spree killers themselves. Tumblr fan site content (text and pictures) was investigated using a combination of visual and textual content analysis, latent class analysis, and hierarchical cluster analysis, using other celebrity fan sites as controls. The general trend was for hybristophiles to have surprising levels of self-knowledge with a small sub-set expressing worrying tendencies to fetishize the killings themselves over and above sexual desires towards the perpetrators. Although the division of hybristophiles into active and passive has been previously shown, we believe we are the first to link this to spree killers who are more or less explicitly advertising their behaviors to their fan base. Much attention has been directed to issues of so-called toxic masculinity and incels, but it is important to appreciate that they do not exist in a vacuum. This material contributes somewhat to understanding the toxic soil in which killers flourish.

Introduction

Rationale

Spree killers—defined as those who willfully injure five or more persons, of whom three or more are killed in a single incident (Dietz 1986)—represent a low absolute risk to life and limb, but exert a powerful effect on public morale, beyond the more obvious impacts on their victims and families of victims (Levin 2014). In addition, to the extent that some spree killers—the younger ones (King and Butler 2019) especially those who seem more influenced by political extremism and sexist ideologies—may represent a manifestation of specifically male failures to acculturate to the modern world, they can be taken as a possible bellwether of underlying borderline pathologies in the culture at large. Although these are not terrorist attacks, the growing influence of some quasi-political extremist masculinist positions, aided in spread by the modern internet, has started to blur some of these boundaries somewhat (Hoffman et al. 2020).

We feel the need to emphasize these facts because they appear lost on a number of recent commentators on spree killings. For instance, some notable public intellectuals, including those with strong pretensions to data sophistication (e.g., de Grasse Tyson 2019) have responded to the almost weekly spree killings in the USA (BBC News 2019) with a high-minded emphasis on the low absolute risk of dying this way compared to, say, car accidents or medical malpractice.

Such commentary, as well as being offensive to victims’ families (among others), also ignores the effect on social cohesion attendant on the knowledge that some of one’s fellow citizens view each other as cannon fodder for their personal rage. It also ignores what spree killings seem to be a symptom of—pathological male responses to perceived status loss or lack of sexual access. These are wider social concerns, which manifest themselves in other areas such as gendered differences in suicide and mental health (McKenzie et al. 2018), and certain forms of misogyny. It would be thus unwise to adopt a crude consequentialist “corpse counting” metric as the sole measure of the importance of such events. How might we seek a greater understanding of the genesis and etiology of such abhorrent behaviors? One set of insights, which helps to set any cultural context, can be derived from evolutionary theory. We should make clear from the outset that we consider the evolutionary theory to be a supplement to and not an alternative to existing, proximate, explanations. Evolutionary—e.g., ultimate explanations provide a context which can explain why a particular trait is maintained in a population (Tinbergen 1963; Tooby and Cosmides 1992). For example, height is a reliable desiderata among females, for male sexual partners, across time and culture (Tooby and Cosmides 1992). A proximate measure of female preferences only reveals that (say) women find it reliably attractive. An ultimate explanation might focus on male partner size as an “all other things being equal” reliable primate indicator of dominance, and further note that this in itself is a preferred trait among female primates that are sexually dimorphic. Indeed it (female sexual selection) is the very engine which creates that aspect of sexual dimorphism (Dixson 1998). One of our goals in this study is to show how providing such an evolutionary context can generate testable hypotheses about phenomena of real (indeed urgent) necessity and provide details contributing to risk assessment and perpetrator identification.

The Evolutionary Context

Sitting at his desk, examining an unusual orchid sent from the other side of the world, Charles Darwin was able to predict the existence of a previously undescribed moth, nearly 6000 miles away, with unusual characteristics, that must exist to feed off it. In 2019, King and Butler (benefitting from insights bequeathed by Darwin) documented a bimodal pattern of male spree killers. This division contained a group of younger ones who exhibited signs of pathological attempts to obtain a certain form of notoriety—the dark cousin to positive social status. Like that orchid, the set of peculiar patterns the killers exhibited implied a co-evolved audience, but, in this case, one of the heterosexual females receptive to those signals. To the best of our knowledge, no one has previously suggested that spree killers and hybristophiles might have a mutually generating element to them.

Spree Killings and Spree Killers

Spree killings are defined as the willful injuring of five or more persons, of whom three or more are killed in a single incident (Dietz 1986). Leaving out those mass murders involving politics or religion, there remains a subset that appears to be motivated by a pathological male response to status. Status is connected to male reproductive success across both time and space, a fact reflected in female desiderata in partners (Buss 2015). Thus, we might expect that males are subject—at the extreme end of the bell curve of measured traits—to potentially pathological defenses of it or reactions to its absence.

Previous research (King and Butler 2019) found that the older spree killers (mean age 41 years) differed markedly in profile from the younger ones (mean age 23 years). While older ones tended to have had successful relationships and careers—that they were now in danger of losing—the moneyer ones fitted the profile of being on the road to reproductive oblivion. For example, they were significantly more likely to have a history of mental health issues, school refusal, and trouble with the law. It is important to note that the older type was not simply an aged version of the younger ones. They typically had families and careers, but had recently lost, or were in danger of losing them. The notion of an average spree killer would, therefore, be highly misleading. The younger and older ones have severely bimodal traits.

Like Darwin’s orchid, if the younger spree killers represent, in part, a pathological response to low status, and the resultant poor reproductive opportunities, this implied a potential female audience.

The Value of Adding Evolutionary Frameworks for Understanding Behavior

Evolutionary insights are not alternatives to existing psychological explanations. They incorporate the recognition that all traits came to be through a non-magical process of evolution by natural selection (Tinbergen 1963). This realization provides constraints on what is psychologically possible in our species (it has to have evolved or be a by-product of something else that could have evolved) and offers additional testable hypotheses about otherwise atheoretical psychological constructs. A mention of some key evolutionary concepts may clarify our goals in adding this set of tools to the analysis of spree killers and their fan base.

In brief, unavoidable asymmetries in minimum parental investment (Trivers 1972), drive human males to honestly signal (Zahavi 1975) a particular set of attractive (as mates) qualities. Human infants are highly demanding, and altricial, meaning that, in some ecologies, these male-displayed qualities include status, dominance, and formidability (the differences do not need to concern us as yet) and, furthermore, in ways that cluster at particular life stage choke points (Stearns 1976).

As an aside, it should be noted that there has been some recent criticism of applying life history theory to within-species differences (Stearns, and Rodrigues 2020). However, it is our contention that such calls are for conceptual clarification, regarding single-axis measures of (say) the fast/slow spectrum, rather than a rejection of the concepts as applied intra-species (Del Giudice 2020). Such clarifications are welcome, and, in any case, are not central to the argument presented here. The key issue here is that the pressures of selection do not fall evenly throughout the human life course but tend to bottleneck at reproductive choke points. In human males, these choke points include timings of pubertal onset, the gaining of social status and recognition, and the maintenance of the same against rivals. It is precisely these last two (age-related) choke points—non-coincidentally linked to status acquisition and (potential) loss, which, we argue, can generate pathological—e.g., violent responses in some males when they are threatened. In the modern era, signaling goes beyond the immediate reach of one’s tribe as it would have existed on the savannah plains of Africa. Lethality and visibility can also be increased by modern technology such as firearms which turn even the weakest into a potential mass killers.

Online Communities—The Social Context of Parasocial Relationships

Spree killings generate considerable media attention (Rocque 2012; Larkin 2009) and public fear. Some attention has been paid to the increase of sights like Kiwi Farms that (until its recent removal) noted spree killer atrocities such as the recent Christchurch murders. Less obvious to the general public is the increasingly large subset of internet users who express a romantic interest in high-profile spree killers (Chen 2012; Warren 2012; Ramamoorthy 2013). There exists a plethora of websites devoted to revering the actions of such criminals that are not unlike the fan pages of pop celebrities. They are full of romanticized GIFs, comics, collages, and manipulated images (Romano 2013). These web groups construct small-world networks, like those of other politically, and socially, fringe, social groups (Oksanen et al. 2014). Small-world networks are social systems comprising groups of individuals who may have little or nothing in common, but whose interaction is facilitated by a unifying factor such as a shared interest in a particular individual or incident, mutual enemies, or friends (Oksanen et al. 2014).

It is a cliché that criminals represent the proverbial bad boy and that this is why they garner attention (Romano 2013). However, in absence of a theory, it is less clear why women, or a subset of them, should find extreme rule-breaking, often combined with violence, sexually attractive. The fact that this attraction is so widespread suggests the trait may be (or may have been in some circumstances) adaptive. In evolutionary terms, the ability and willingness to flout rules can be interpreted in part in terms of the status acquisition. Individuals who exhibit an attraction for such bad-boy types are likely to exhibit overt sexual behavior, use an unrestricted socio-sexual strategy, and exhibit an increased interest in images showing heightened sexual arousal (Herold and Milhausen 1999; Simpson and Gangestad 1992; Tombs and Silverman 2004). Females showing these preferences are perhaps seeking partners who could (maybe in the past) facilitate reproductive success in the short-term, as opposed to those seeking parental investment.

One possibility is that the patterns of attraction exhibited by hybristophiles are similar to those patterns of attraction that would ordinarily be exhibited by fans of celebrities (Romano 2013). This maps to the concern expressed by some commentators that media figures may exert harmful influences over their respective follower networks (Zhou and Whitla 2013; Brown and Fraser 2004; Pleiss and Feldhusen 1995).

Celebrity Culture and Individual Personality

The idolization of persons in the media seems to be an extension of identity development through adolescence, offering individuals myriad possible selves to observe and potentially replicate (Maltby et al. 2006; Davis 2013; Larson 1995). Adolescence is marked by the transition from parental identification, towards the emergence of a personally significant, and socially endorsed, identity (Steinberg and Silverberg 1986; Cramer 2001; Erikson 1968; Davis 2013). Para-social relationships, asymmetric between an individual and media figures, may perform important social and emotional functions (Greene and Adam-Price 1990). Indeed, the behavior exhibited during para-social relationships is often reflective of behavior exhibited during social relationships, in reality (Tuchakinsky 2010; Cowley 2011).

In respect of adults’ attachment to celebrities, Lasch (1991) argues that society is becoming increasingly supportive of narcissistic individuals and that this leads to the emergence of celebrities as icons (who at least display, if they do not possess such qualities) with whom people seek to identify. In addition, Riesman (2001) suggested that (Western) society was transitioning to a stage of other-directedness, where individuals are increasingly need the approval of others (Zinkhan and Shermohaman 1986). If this picture is broadly true, then it implies that mass media in contemporary society has created individuals whose glory and fame are utilized by their audience as a source of self-satisfaction or life direction (Lee et al. 2008). Such narcissistic internal models of self might act as supernormal stimuli to the human self-image, in much the same way as a long yellow stick with a red spot generates a disproportionately responsive behavior in the chick (Tinbergen and Perdeck 1950). An evolutionarily adaptive trait—such as a signal-to-response interface—will produce proximate mechanisms to make said trait manifest in each organism (Tinbergen 1963).

Hybristophilia

What is happening to the individual at this proximate level—in terms of feelings, desires, behaviors, and cognitions—as regards female desire for bad boys? The term hybristophilia has been applied to women who are attracted to violent criminals (Sharma 2003; Gurian 2013). “Hybristophilia is a paraphilia of the marauding/ predatory type in which sexuerotic arousal and attainment of orgasm are responsive to and contingent upon being with a partner known to have committed an outrage or crime, such as rape, murder or armed robbery” (Money 1986, p. 263). Hybristophilia admits of degrees and is far more prevalent in women (Vitello 2006; Purcell and Arrigo 2006). Hybristophiles may be the victims of physical or sexual abuse, resulting in low self-esteem and feelings of insecurity, predisposing the individual to deviant sexual preferences, and criminality (Gurian 2013; Vitello 2006). However, support for such a hypothesis is far from compelling. Isenberg (1991) suggested that women who engage in relationships with criminals evaluate their relationship as a companionship, rather than a sexual, or romantic, coupling. Hybristophiles may also wish to collaborate with a violent offender to express their own violent tendencies, or because (at a conscious level) they want to rehabilitate the criminal (Vitello 2006; Parker 2014).

This mixed picture of attraction has led to a two-fold typology of hybristophiles (Parker 2014). Passive hybristophiles have little interest in committing criminal behavior but derive sexual pleasure from seeking relationships with specific individuals who have committed criminal acts (Parker 2014). Aggressive hybristophiles derive sexual pleasure from the criminal act itself and, sometimes, may coax a partner into committing a crime with them (Parker 2014).

As yet, there is limited consensus about the diagnosis, etiology, and symptomology of hybristophilia (Slavikova and Panza 2014). It could be that it forms the extreme end of a continuum of sexual desire, rather than being viewed as a disorder. That many authorities have regarded hybristophiles as similar to fans of celebrities (Slavikova and Panza 2014; Böckler and Seeger 2013) is, perhaps, because of a lack of attention to possibly adaptive nuances of the trait. Literature addressing the emergence of virtual fan communities of hybristophiles is likewise limited (Böckler and Seeger 2013, p. 309). Relevant literature has neglected to mention any possibility of paraphilia being present, and has, instead, focused on examining the physical attributes of the fan network as a whole (e.g., Oksanen et al. 2014). In light of the aforementioned shortcomings, the current study aims to investigate the possibility of hybristophilia being present in fan networks, and to compare any such hybristophiles to fans of celebrities. These separate strands of psychological research—clinical and organization—will be considered under an evolutionary framework, which we hope to have established that we see as a perspective that adds value to, rather than seeks to replace, existing ones.

The current study compares the fan bases of two prominent spree-killer events, in order to test the idea that hybristophilia, in some contexts, has the quality of being a sexually receptive response to male murderous displays in a cohort of females.

Method

Data Collection: Context of the Fanbase for Spree Killers

The Columbine massacre was a spree killing that occurred in April 1999. In the course of it, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold shot 12 students and one teacher to death before committing suicide. James Egan Holmes was the perpetrator of a spree killing in July 2012 that resulted in the deaths of 12 people at a Century movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. We selected these two cases for study because both attracted considerable media attention, resulting in the formation of large fan bases. In both cases, a specific, and expressed, desire for notoriety was noted as a motive for the attacks. Finally, they were selected because upon preliminary investigations it was revealed that the fans of the Columbine massacre are typically between the ages of 20 and 25, and the fans of the James Holmes massacre are typically between the ages of 15 and 20, allowing for age-based comparisons.

The Internet has enabled the dissemination of sexually oriented material, allowing for the easy informal exchange of text, images, and videos (Gackenbach 2011). The creation of web forums that allow individuals to remain anonymous has encouraged the spread of material previously thought of as taboo (Gackenbach 2011; Oksanen et al. 2014). In particular, female-generated pornography and erotica (much of which is written) has become much more available for scrutiny (Salmon and Symons 2003). Many of the supposed hybristophiles have turned to the micro-blogging site Tumblr to express their desires (Chen 2012).

In the current study, the aggressive/passive typology is investigated using an evolutionary framework. Further, it will also explore the implications of the theory that individuals incorporate negative attributes of a desired partner into their self-concept (Slotter and Gardner 2012).

We focused on female hybristophiles who expressed an interest in the case of James Holmes (aged 15–20 group JH) or those who expressed an interest in the Columbine massacre (aged 20–30, group CB). To control for the celebrity element we used, for comparison purposes, the Tumblr blogs of fans of standard celebrities, namely fans of One Direction (aged 15–20, group 1D) and fans of Ryan Gosling (aged 20–25, group RG).

The goal was to generate descriptions of themes and attributes from collections of images which would allow for the quantification and comparison of data sets (Van Leeuwen and Jewitt 2001). To this end, a mixed-method approach was used. Data were initially analyzed using both latent and traditional content analysis. In the former, the patterned (content) and projective (interpreted meaning) of the manifest elements of the data was examined (Potter and Levine-Donnerstein 1999). In the latter instance, the focus was on counting occurrences of different elements (Stepchenkova and Zhan 2013). Thereafter, data were subjected to Latent Class Analysis (LCA). Visual depictions were analyzed using hierarchical cluster analysis.

Procedure

Following institutional ethical approval for the study, data were collected from the online micro-blogging site Tumblr (www.Tumblr.com). Tumblr allows its users to create short-form blogs comprised of photos, GIFs, videos, and written entries. Tumblr was (at the time) the most suitable site for this study in terms of size and accessibility relative to other micro-blogging sites such as Twitter and Instagram.

A pilot investigation identified the tags which produced relevant results. A search was conducted using the following tags and search words: The tags for group JH were “James Holmes” and “hybristophilia,” and the tags for group CB were “Columbine” and “hybristophilia.” The tags for group 1D were “Onedirectioners” and “obsessed,” and the tags for group RG were “Ryan Gosling” and “obsessed.” The units of image analysis and text analysis were defined as images, and text passages, of approximately 400 words appearing on the Tumblr blogs of self-confessed “hybristophiles”, who professed an attraction to:

-

James Holmes, and between the ages of 15 and 20

-

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and between the ages of 20 and 25

-

One Direction, and between the ages of 15 and 20

-

Ryan Gosling, and between the ages of 20 and 25

The users’ age was determined by examining the written biographical content on their blogs. Only those with verified (by Tumblr itself) ages were used. A two-stage data-identifying process was followed. First, the 200 most recent images, that could be defined as units of analysis, were selected independently for each group. Second, a random number table was then used to select 50 images for analysis from each group. This process was repeated for the text data. Specifically, the 30 most recent passages, that could be defined as units of textual analysis, were selected independently for each group, and a random number table was used to select five passages for analysis for each group. In total, 200 images and 20 passages were selected for analysis. A full protocol is available from the authors on request.

Four analysts, naïve as to the research questions, were recruited to complete data analysis. Approximately 4 h of each analyst’s time, across two separate occasions, was required. Two were male (aged 34 and 39 respectively) two were female (aged 19 and 27 respectively). They were not paid for involvement but were warned about the possibility of viewing disturbing material. They were reminded of their right to withdraw at any time.

Data Analysis

Data analysis had four phases, with a similar process in place for both media and text data. The primary researcher undertook a literature review, through which they developed a theory-driven coding scheme. During this phase, variables were discussed and defined with a second member of the research team, before codes were agreed. Codes were developed into categories by organizing the initial codes under higher-order headings, agreed through discussion, and revision. This process resulted in five categories which accounted for all the variables of the data and which appear to be mutually exclusive (Van Leeuwen and Jewitt 2001). Category 1 was “sexual content” with nominal values being explicit, implicit, and none. Category 2 was “violent content” with nominal values being depicted, implied, and none. Category 3 was “tool of notoriety” with nominal values being yes (present) and no (absent). Category 4 “subject of image” was concerned with whether the image’s primary focus was on the individual or on the act that led to the individual achieving notoriety. The nominal values here were act and individual. Category 5 was “realism” with the ordinal values being very realistic, realistic, moderately realistic, and not realistic. Pilot tests were conducted to establish reliability, and Krippendorf’s alpha (KALPHA) values were accepted.

In the initial phase of textual analysis, theory and literature again played an inductive role, resulting in 31 codes being identified. All of the variables were concerned with latent pattern content, with the exception of variables 5, 7, 10, 11,31, and 33 which examined latent projective content and of variables 3, 23, 28, 29, and 32, which examined manifest content. Each of the codes was assigned a distinct label to make analysis and interpretation of the data easier. A pilot test was run to increase reliability levels with the results shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Image analysis alpha coefficient values of inter-rater reliability

| Variable | Krippendorf’s alpha | ||

| Pilot test 1 | Pilot test 2 | Test 1 | |

| Sexual content | 1.000 | - | 1.00 |

| Violent content | 0.834 | 0.966 | 0.969 |

| Realism | 0.755 | 0.872 | 0.931 |

| Subject of image | 1.000 | - | 1.000 |

| Tool of notoriety | 0.866 | - | 1.000 |

In phase two, the primary researcher trained the four analysts to ensure that the coding scheme and process were fully understood. In phase three, inter-rater reliability was determined through the use of a pilot study. Specifically, the analysts were instructed to code, independently, and without consultation, a sample of 30 images, and 5 text-based data that were similar to, but not part of the actual research corpus. A Kalpha value of 0.80 was accepted. In the final phase, each analyst viewed 100 individual images separately, with analysts one and two coding all of the images from groups JH and RG, while analysts three and four coded all of the images from groups CB and 1D. For every image, the analyst noted a value for each of the five variables. Each analyst coded all 20 of the text data passages. Each analyst was then required to identify the presence or absence of the 31 codes in each passage as a whole, resulting in each code being assigned a “yes” or a “no”. Codes 1–23 were examined across the data set, while codes 24–31 were examined in relation to passages for the JH and CB groups as these codes are directly related to the topic of hybristophilia (e.g., crimes committed or imagined) and are not relevant to the analysis of group 1D and group RG.

The image-based data were then subjected to Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to identify discrete, mutually exclusive, latent classes of hybristophiles/celebrity fans based on how their images and passages were categorized into categorical variables forming multivariate data (Costa et al. 2016). See Table 2 for the results of the latent class analysis.

Table 2. Results of latent class analyses

| LL | BIC(LL) | Npar | |

| 1-Cluster model | − 843.2613 | 1734.2075 | 9 |

| 2-Cluster model | − 773.9337 | 1637.9389 | 17 |

| 3-Cluster model | − 757.6989 | 1647.8558 | 25 |

| 4-Cluster model | − 749.4076 | 1673.6596 | 33 |

| Chi Squared statistics | |||

| Degrees of freedom (df) | 126 | p-value | |

| L-squared (L2) | 134.7911 | 0.28 | |

| X-squared | 160.1830 | 0.021 | |

| Cressie-Read | 140.1448 | 0.18 | |

| BIC (based on L2) | − 532.7969 |

LL refers to log likelihood. The lowest BIC value was in the 2-cluster model. (Random seed 357445. Best start seed 1901016)

Textual Analysis

To validate and further explore the findings from the image analysis, 23 variables were investigated in relation to the passages from all of the groups using hierarchical cluster analysis. Nine variables were exclusively investigated in relation to the passages from groups CB and group JH using Fisher’s exact test. Given the small sample, it was reasonably assumed that the sampling distribution of the test statistic was deviant from a chi-square distribution, rendering chi-square analysis not applicable to the data (Field 2013). However, the clusters were qualitatively described using the results of the CA coding and quantitatively described using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Latent Class Analysis

In an effort to identify types of hybristophile shown by online content, the variables pertaining to sexual content, violent content, tool of notoriety, subject of image, and realism were subject to latent class analysis, using the latent class analysis software Latent Gold (Vermunt and Magidson 2000). Latent-class analysis can be considered a probabilistic extension of K-means cluster analysis, with the advantage that it is model-based, thereby affording the use of statistical criteria for determining various different cluster solutions. The analyst can use the Bayesian information criterion to choose between differing models. The one with the lowest BIC is generally preferred as indicating a good balance between model fit and parsimony (defined in terms of relatively few parameters). Models can be created through sequentially relaxing assumptions regarding the covariance structure of the indicators. Given that it had the lowest BIC of alternatives, a two-class model appeared to be the best fit for the data. This was confirmed by analysis of the bootstrap likelihood ratio (Tein et al. 2013).

Latent Class Profiles

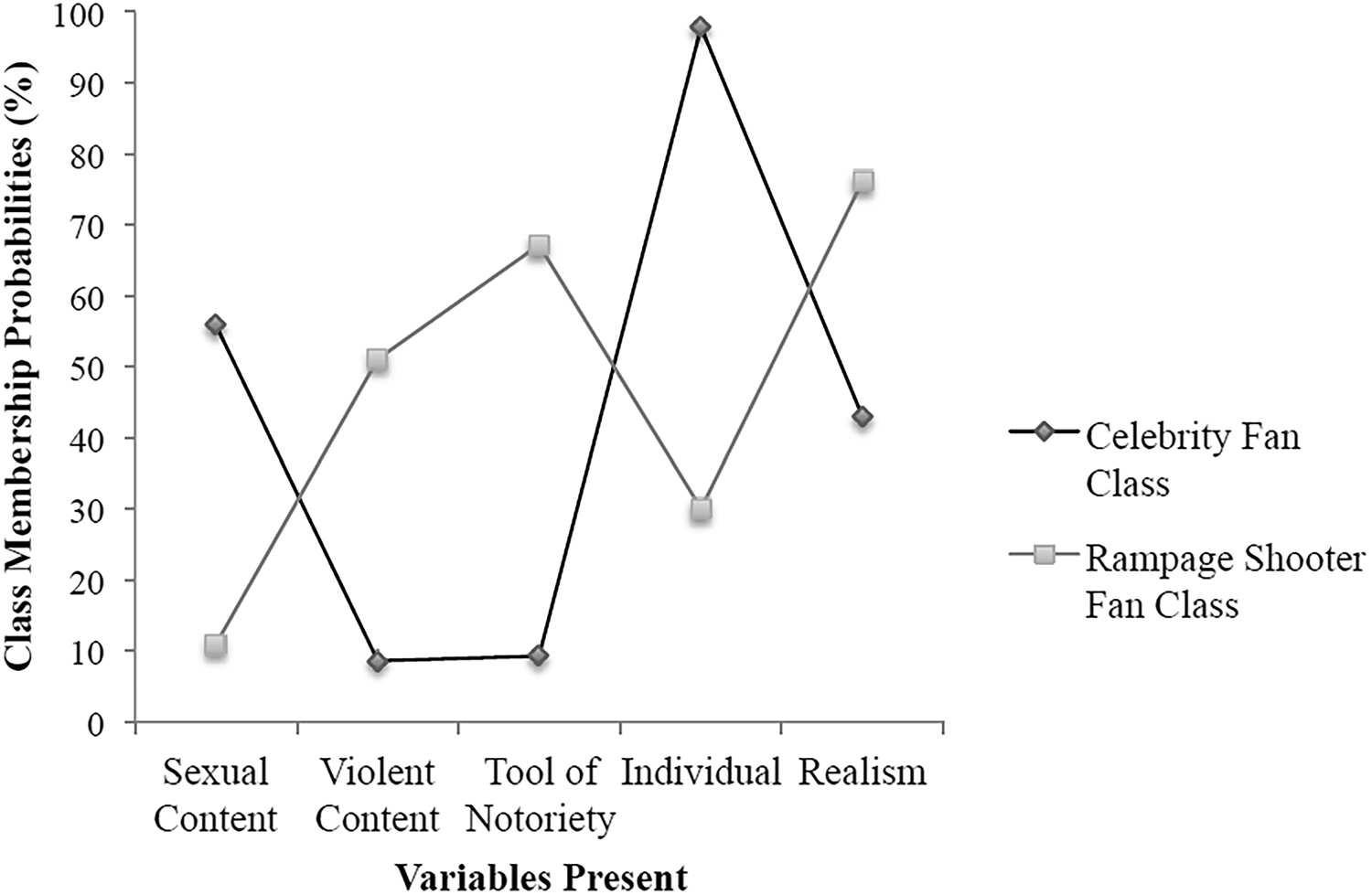

Upon investigation of the class-specific trajectories, class 1 was labeled “Celebrity Fans” and class 2 was labeled “Rampage Shooter Fans” (see Fig. 1). The celebrity fan class accounted for 61% of the sample, while the Rampage Shooter class accounted for 39% of the sample.

A large proportion of the Celebrity Fan class was comprised of images pertaining to the James Holmes fan group (group JH) (37.05%), the One Direction fan group (group 1D) (28.69%), and the Ryan Gosling fan group (group RG) (28.69%). By comparison, only 8.19% of the Celebrity Fan class was comprised of images pertaining to the Columbine fans (group CB). Images categorized into the Celebrity Fan class tended to exhibit both implicit and explicit sexual content. Furthermore, they tended to focus primarily on the act itself, rather than the perpetrator. Additionally, images categorized into the Celebrity Fan class had a high probability of not featuring the subject’s tool of notoriety and of not exhibiting violent content. Finally, the Celebrity Fan Class exhibited a relatively stable amount of very realistic, realistic, moderately realistic, or not realistic content (see Table 3).

Table 3. Textual variables from Tumblr posts and illustrative fan types

| Variable name | Theme |

Themes illustrated by sample Tumblr posts Sample illustrative passage |

Representative of which clusters? (r/n) Significance (Fisher’s exact test p < .05)* = significant difference from non-starred clusters Clusters demonstrating trait are bolded |

| 1 Net-pos | Addressing network in positive way | “I know you all feel the same, we all love James and that’s what has brought us together! I'd do anything for you guys because I love you all more than anything or anyone I've ever loved before and I finally feel accepted” |

Columbine (0/4)* Holmes (6/6) Celebrity (4/10) |

| 2 Net-neg | Addressing network in a negative way | “What pisses me off though, are these teenage groupies who fake “hybristophilia” to look “cool” and that probably includes you reading this—idiot.” |

Columbine (2/4)* Holmes (0/6) Celebrity (0/10) |

| 3 Net-name | Referencing network name |

“I am the queen Holmie so bow down and follow bitches jk I love you all < 3 < 3 < 3″, See also “One Directioners”, “Columbiners”, “Goslings” |

Columbine (0/4) Holmes (6/6)* Celebrity (4/10) |

| 4 Phys-attract | Expressing interest in Ss physical attributes | “They are literally the hottest things on the planet, especially harry with his soft brown locks and those muscly arms!” |

Columbine (0/4)* Holmes (5/6) Celebrity (8/10) |

| 5 Person-pain | Identifying with Ss personal pain | “The truth is I'm misguided I know … I feel different but I know James did too, we both hurt” |

Columbine (0/4) Holmes (5/6)* Celebrity (1/10) |

A large proportion of the Rampage Shooter Fan class was defined by group CB (51.28%). Of the Rampage Shooter Fan class, 7.69%, 21.79%%, and 19.23% were comprised of images relating to group JH, group 1D, and group RG respectively. Images categorized into the Rampage Shooter Fan class had a high probability of exhibiting both depicted, and implied, violent content, and had a high probability of being focused on the act, rather than the individual. Additionally, and perhaps surprisingly, images categorized into the Rampage Shooter Fan class tended to display no sexual content. Finally, images categorized into the Rampage Shooter Fan class had a high probability of being either realistic, or very realistic, and tended to feature the subject’s tool of notoriety. For full latent class profiles see Table 3. For a visual representation of the results see Fig. 1. For the sake of visual representation, all of the coding categories were converted into nominal variables. The presence (yes values) of these variables was represented on a graph (see Fig. 1).

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: Variables 1–23

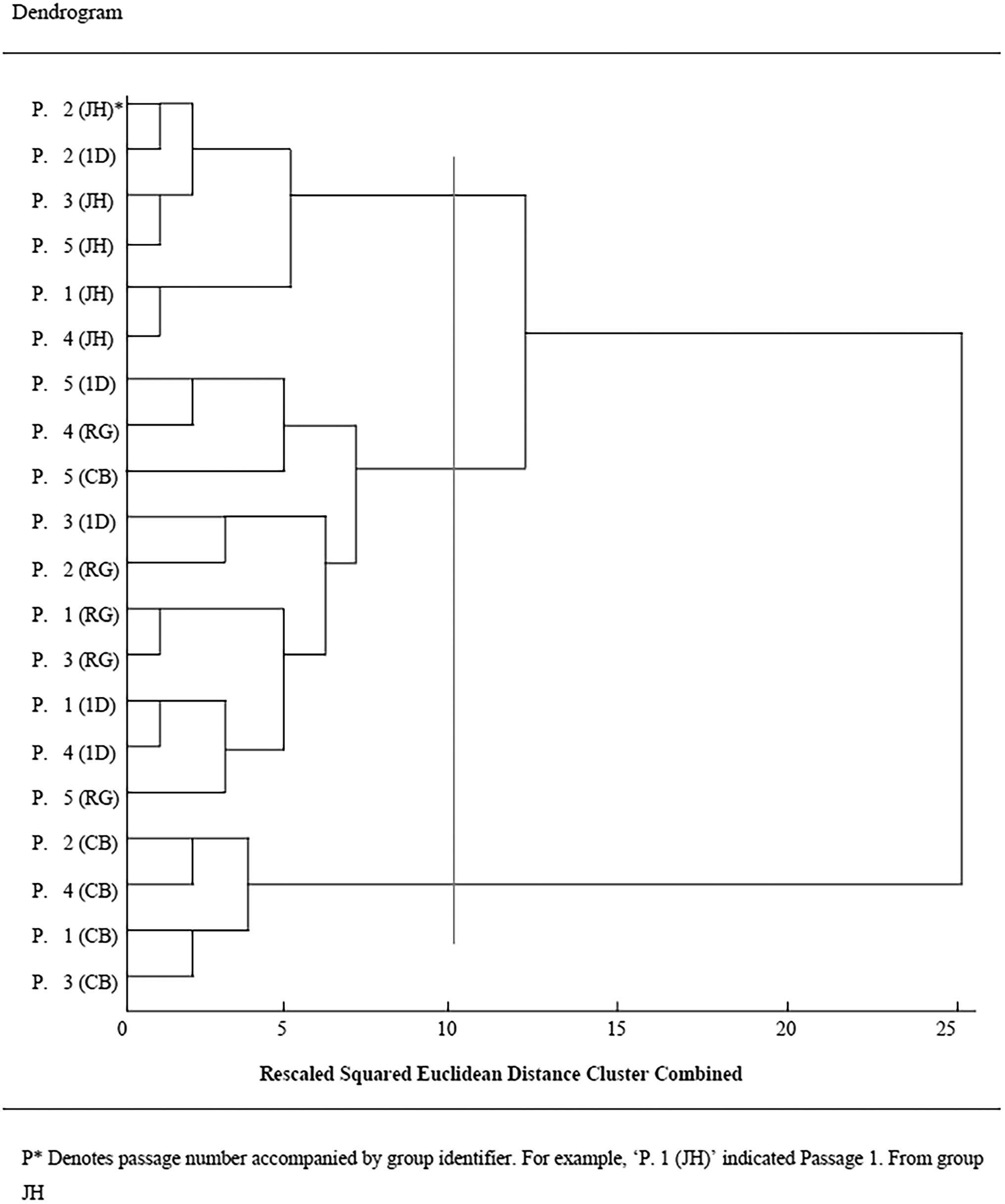

A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method was run on 20 cases of the textual representation of fandom. Each of these was categorized using the coding categories (1–23) previously discussed (and displayed in Table 4). The number of clusters that best represented the data was determined by examining the agglomeration schedule (see Table 5). A clear demarcation point in distance coefficients was observed, suggesting that a 3-cluster solution best fits the data. Specifically, the 3-cluster solution represented the largest decrease in squared Euclidean values, which indicated that the three clusters described by the solution were relatively dissimilar. This variety of grouping is commonly referred to as agglomerative hierarchical clustering.

Table 4. Latent class profiles of visual fan content.Latent class profiles

| Variable | Celebrity fan class % (n = 122) | Rampage shooter fan class % (n = 78) |

| Sexual content | ||

| None | 44.12 | 89.09 |

| Implicit | 16.84 | 0 |

| Explicit | 39.03 | 10.81 |

| Violent content | ||

| None | 91.38 | 48.86 |

| Implicit | 7.88 | 28.97 |

| Explicit | 0.74 | 22.17 |

| Tool of notoriety | ||

| No | 90.66 | 32.77 |

| Yes | 9.34 | 67.23 |

| Subject of image | ||

| Individual (perpetrator) | 97.80 | 29.82 |

| Act | 2.20 | 70.18 |

| Realism | ||

| Not realistic | 21.76 | 5.23 |

| Moderately realistic | 35.41 | 18.51 |

| Realistic | 22.25 | 25.31 |

| Very realistic | 20.59 | 50.96 |

Table 5. Agglomeration schedule for hierarchical cluster analysis

| No. of clusters | Coefficients last step | Coefficients this step | Change |

| 2 | 96.20 | 70.81 | 25.39 |

| 3 | 70.75 | 58.75 | 12.06 |

| 4 | 58.75 | 50.96 | 7.79 |

| 5 | 50.96 | 40.08 | 5.88 |

Cluster Profiles: Variables 1–23

The first cluster was entirely defined by passages from group CB and was subsequently labeled the “Columbine” cluster. The second cluster represented all 4 passages from group JH, and 1 passage from group 1D, and cluster 2 was labeled the “Holmes” cluster. Finally, the third cluster represented all 4 passages from group RG, 3 passages from group 1D, and 1 passage from group CB. Cluster 3 was labeled the “Celebrity” cluster. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine whether or not the clusters differed significantly with respect to the variables examined (see Table 3).

It is worth noting that the type of explicit sexual content exhibited by the Columbine cluster, and that by the Holmes cluster, was qualitatively different. The Holmes cluster typically exhibited explicit sexual content pertaining to the individual’s physical attributes, while the Columbine cluster typically exhibited explicit sexual content pertaining to the individual’s crime, with many passages describing a sexual attraction to the rampage shooting itself rather than to the individual.

The results of the hierarchical cluster analysis are illustrated by the dendrogram in Fig. 2. The cut line indicates the 3-cluster solution selected for examination. The general squared Euclidean distance coefficient was used to create the proximity matrix that constructed the present analysis. The dendrogram was then constructed using the increase in the sum of the square method. Five passages from each group were analyzed, represented on the Y-axis. The X-axis represents the squared Euclidean distances at which the clusters were combined during each step of the hierarchical cluster analysis.

Fisher’s Exact Test: Variables 24–31

The presence or absence of variables 24–31 was investigated in relation to the passages pertaining to group JH and group CB using Fisher’s exact test (recall that these variables pertain to the explicitly criminal aspects of the fan appreciation and thus are not relevant to the mere celebrity groups). The results of these tests are shown in Table 3, with some key findings reiterated below.

Four of the passages from group JH made reference to the theme of redemption in relation to the subject, while none of the passages from group CB made such reference. reference to the theme of redemption. This difference was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). The writers of four passages from group JH and four passages from group CB were observed to recognize that the criminal act was morally wrong, a non-statistically significant difference.

All five passages from group CB exhibited knowledge of the subject’s ideology, and the writers of four of those passages were observed to identify with the subject’s ideology. In contrast to this, none of the passages from group JH were observed to exhibit knowledge of the subject’s ideology or to identify with the subject’s ideology. These differences were both statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test p < 0.05).

The writers of four of the passages from group CB expressed a desire to commit a rampage shooting attack themselves, and three of the passages described their own criminal impulses. None of the writers of the passages from group JH expressed either a desire to commit a rampage homicide attack, or described having criminal impulses. Both these differences were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05 in each case.

All of the passages from group CB were observed to describe an attraction to multiple criminals, and, additionally, all of the passages from group CB were observed to have a romantic attraction toward the criminal acts committed by these criminals. In contrast to this, none of the passages from group JH mentioned other criminals and none of those passages referenced an attraction to the actual criminal act. Both of these differences were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Findings

Independent confirmation of psychological constructs from multiple perspectives adds to the validity of said constructs. The clinical literature has described a phenomenon—a typology of hybristophiles divided into those who eroticize the perpetrators, and those who wish to emulate them. It is notable that a typology of spree killers, framed in evolutionary life history terms, reveals a pattern that similarly predicts and helps to explain this pattern: specifically that it is what we might predict from research showing that the younger spree killers typically have a profile that is advertising their formidability in a way that might be found sexually attractive to a class of hybristophiles (King and Butler 2019). In this study, we investigated self-described hybristophiles on Tumblr. These hybristophiles who expressed a romantic interest in high-profile rampage shooters were compared to celebrity fan communities in order to explore some of the expressed erotic/fantastical content with respect to same. Hybristophilia is not mere celebrity worship, although some forms of it do share common elements. Interestingly the more aggressive hybristophiles—those who are aware that their erotic fixation centers on murderous acts, at least those who express themselves as such on social media—show a level of self-awareness about the phenomenology and sequelae of their erotic fixations.

It should be noted that nearly all hybristophiles identified as female (and very few males identified as homosexual) but there are only limited things that can be done to confirm this. Tumblr asks for age and sex but that cannot be independently confirmed. On the other hand, the online community themselves is, like many online communities, a place of tribalism, in-jokes, and secrets. They police their own boundaries quite effectively and, for example, seem to themselves be aware of the differences between hardcore hybristophiles and those with a more dilettante attitude. In addition, they all talk to one another as if they were women. We were reminded here of Rosenhan’s classic (1973) paper on Being Sane in Insane Places, where the pseudopatients pretending to have mental illness in asylums were only spotted by other (genuine) patients.

Hybristophiles are not a homogeneous group. Our exploratory typological investigations suggest that the Columbine (CB) fans differed significantly from the fans of James Holmes (JH), One Direction (1D), and Ryan Gosling (RG). Perhaps surprisingly, the fans of JH exhibited similar patterns of visual representation—eroticism centered on the perpetrator—to the fans of 1D and RG.

The fans of the Columbine Massacre, presented here, seem to represent the more aggressive hybristophile type (Parker 2014), and the evidence for this, comes from both the image and textual analyses. These findings support the theory advanced by Vitello (2006) that individuals’ violent tendencies, as portrayed through images and text, underlie and contribute to, the development of hybristophilia. The images from this group tended to be high in violent realism, but with relatively low sexual content. The hybristophilia here does center more on the crime than the perpetrator, who appears more as a mediating object of the fetish, rather than the focus itself. For example, there is no talk with this group about changing the perpetrator, and often open acknowledgement that they would not desire them but for the crimes committed.

Compared to all the celebrity fans, the passages of the Columbine and John Holmes (JH) fans articulated strong and more frequent romantic emotions directed at the subject of their attraction. However, unlike the JH fans, the Columbine fans tended to describe these emotions as long-lasting, innate, and expressing admiration for the subject of their attraction. This theme also occurred with the celebrity cluster. This suggests that the Rampage shooter fans (e.g., the aggressive hybristophiles) do possess a potent romantic attraction for their subjects, that is not ordinarily associated with celebrity worship, and, in the case of the Columbine fans, that this attraction is long-lasting and innate (Money 1986; Purcell and Arrigo 2006). The writers of the passages in the Columbine cluster were observed to express a negative self-concept more often than the writers of passages in the Holmes cluster or in the celebrity cluster. This finding suggests that low self-esteem and the possession of a negative self-concept can contribute to an individual developing hybristophilia (Gurian 2013).

Finally, the Columbine fans displayed significantly more knowledge of, and identification with, the shooters’ ideology, demonstrating the Columbine fans’ interest in the true nature of the criminal acts and which suggests that these individuals may represent an audience responding to the Columbine shooters’ communicative strategy (Larkin 2009). Increasingly, some shooters are leaving behind manifestos of their beliefs, attitudes, and rationalizations (Minihane et al. in revision) and it is likely that this particular type of hybristophile will be particularly engaged with this sort of material.

The visual representations utilized by the James Holmes fans were similar to the visual representations utilized by the celebrity fans—with low levels of violence and high levels of sexualized depiction. However, this was not the whole story. The textual analysis revealed that the passages written by the fans of JH differed significantly from the passages written by the celebrity fans. The JH fans would appear to fit the pattern of passive hybristophilia (Parker 2014; Woodworth et al. 2013). The textual passages from the Holmes and Celebrity cluster tended to have themes of redemption and change, with the fantasist in the role of redeemer. This pattern did not emerge with the CB hybristophiles, and these would fit with Vitellos’ (2006) description of hybristophiles who believe that they can rehabilitate the perpetrator. The more aggressive hybristophiles harbored no such fantasies. The more passive hybristophiles had more in common with the celebrity worshippers in this respect: with heightened interests in images implying sexual arousal (Romano 2013; Herold and Milhausen 1999).

There were emotional differences between the celebrity fans and the more passive (JH) hybristophiles. This manifested in passages describing an imagined emotional connection more often than either the celebrity cluster and the Columbine cluster. This may be a function of the difference in age groups. Adolescent fantasists have different uses for celebrities in their idealization than do more mature—e.g., of possible reproductive age—fans. While the fans of 1D and of JH often addressed their respective small network in a positive way, and used their network names (Oksanen et al. 2014), the fans of RG and CB did not, suggesting that only the younger fan groups from small-world networks. However, it is worth appreciating that there may be still cause for concern, even if age differences, and not hybristophilia, describe the differences between the CB and the JH fans, because the illusion of intimacy between media consumers, and media professionals, may enable adolescents to develop their own personalities and identities that are then used in future social relationships (Giles and Maltby 2004). Additionally, adults also use celebrities as a source of life direction, often emulating the behavior of their celebrity icons (Lee et al. 2008). If adolescents use their parasocial relationship with a rampage shooter to form blueprints for their future relationships, or if adults use the behavior of a rampage shooter as inspiration for their own behavior, this is also worthy of concern, albeit of different types.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it should be regarded as a preliminary scouting out of the territory of hybristophile typology, as represented in social media and thus is subject to the usual exhortations about larger data sets and replications. It is worth noting that, although Tumblr operates an age verification system, it is likely not beyond the capabilities of some tech-savvy individuals to circumvent this. While true, the likely result of any such actions would be people claiming to be older than they are, to access 18 + material, so the effect on our age controls would be minimal. It is worth noting that the task of integrating clinical, criminal, and theoretical (e.g., the various types of causation outlined by Tinbergen 1963) is still in the early stages as regards hybristophilia. While it is encouraging that the beginnings of an adaptive story, along with a personal ontogenic (e.g., individual development differences) and mechanistic (e.g., mediating thoughts and fantasies) account of the types of hybristophilia are being constructed, they are far from complete.

Future Directions

Future directions could include investigating the existence of hybristophile communities using other social networking sites such as Facebook™, Instagram™, and Tiktok™, although it is likely that these sites will (and with justification) shut down such access. A very small number of self-identified homosexual hybristophiles were encountered in the course of this study. There were too few, and with insufficient material to add them meaningfully to the analysis, but this could change in the future.

The feasibility of constructing aggregated profiles of subgroups of individuals using the pictorial, and literary data has, we think, been established here. It is perfectly appropriate, and possibly useful in terms of risk assessment, to conduct analysis of online visual and literary communication materials, messages, and symbols. These seem legitimately objects of study, revealing information that outreaches their intended purpose; most notably communicating information about the cognitive and sociological state of their creators (Krippendorff 2004).

Recently, some spree killers have begun to issue manifestos about their self-described motives. It is highly likely that these will have measurable effects on their fanbase and should probably be a source of concern for law enforcement and clinical intervention, and risk assessment.

Conclusion

We have identified a group of Internet users expressing a romantic attraction for individuals who commit condemnable acts of rampage homicide. Through explorative investigations, these fans are measurably distinct from celebrity fans, suggesting that the behaviors in question are not simply celebrity worship. Furthermore, variability among these individuals has been observed, suggesting that there are two broad types of rampage shooter fans, potentially representing either passive or aggressive hybristophilia. The aggressive ones may well represent a risk on their own, as their obsession with the acts, rather than redeeming and reforming the perpetrators, could be of concern to law enforcement or mental health professionals. A convergence of theoretical (e.g., evolutionary and clinical) and practical (e.g., forensic and law enforcement) models of spree killings seems attainable and desirable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Approved by University College Cork 09/2017. Secondary data only.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

BBC News (2019) US saw highest number of mass killings on record in 2019, database reveals. Online news source https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-50936575. Retrieved 15 Jul 2021

Böckler, N; Seeger, T. Böckler, N; Thorsten, S; Sitzer, P; Heitmeyer, W. Revolution of the dispossessed: school shooters and their devotees on the web. School Shootings: International Research, Case Studies and Concepts for Prevention; 2013; New York, Springer: pp. 309-339. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5526-4_14]

Brown, WJ; Fraser, BP. Singhal, A; Cody, MJ; Rogers, EM; Sabido, M. Celebrity identification in entertainment-education. Entertainment-education and social change: History, research, and practice; 2004; Maywah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc: pp. 97-116.

Buss D (2015) Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. New York. Psychology Press

Chen A (2012) Why James Holmes has fans on the Internet. Retrieved on 1st July 2019 from http://gawker.com/5930565/why-james-holmes-has-fans-on-the-internet

Costa JJ, Matos AP, Rosario MDP, Ceu Salvador MD, Luz Vale-Dias MD, Zenha-Rela M (2016) Evaluating use and attitudes towards social media and ICT for Portuguese youth: the MTUAS-PY scale. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences 99–115

Cowley C (2011) Face to Face with Evil: Conversations with Ian Brady. London. John Blake Publishing

Cramer, P. Identification and its relation to identity development. J Pers; 2001; 69, 5 pp. 667-688. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.695159]

Davis, K. Young people’s digital lives: the impact of interpersonal relationships and digital media use on adolescents’ sense of identity. Comput Hum Behav; 2013; 29, 6 pp. 2281-2293. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.022]

de Grasse Tyson N (2019) Tweet on spree killings https://tinyurl.com/mfsrzzmy. Accessed 31 May 2120

Del Giudice, M. Rethinking the fast-slow continuum of individual differences. Evol Hum Behav; 2020; 41, 6 pp. 536-549. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.05.004]

Dietz, PE. Mass, serial and sensational homicides. Bull N Y Acad Med; 1986; 62, pp. 477-491.

Dixson, AF. Primate sexuality: comparative studies of the prosimians, monkeys, apes, and human beings; 1998; USA, Oxford University Press:

Erikson EH (1968) Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). London. WW Norton & Company

Field A (2013) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. London. Sage

Gackenbach J (ed) (2011) Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal implications. Cambridge (Massachusetts) Academic Press

Giles, DC; Maltby, J. The role of media figures in adolescent development: relations between autonomy, attachment, and interest in celebrities. Personality Individ Differ; 2004; 36, 4 pp. 813-822. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00154-5]

Greene, AL; Adams-Price, C. Adolescents’ secondary attachment to celebrity figures. Sex Roles; 1990; 22, pp. 335-347. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00289224]

Gurian, EA. Explanations of mixed-sex partnered homicide: a review of sociological and psychological theory. Aggress Violent Beh; 2013; 18, 5 pp. 520-526. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.007]

Herold, ES; Milhausen, RR. Dating preferences of university women: an analysis of the nice guy stereotype. J Sex Marital Ther; 1999; 25, 4 pp. 333-343. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00926239908404010]

Hoffman, B; Ware, J; Shapiro, E. Assessing the threat of incel violence. Stud Confl Terror; 2020; 43, 7 pp. 565-587. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1751459]

Isenberg S (1991) Women Who Love Men Who Kill. New York: Simon and Schuster

King R, Butler N (2019) Running amok: spree killers viewed through the lens of evolutionary theory. Mank Q 60(2)

Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. The Sage Commtext Series, Sage Publications Ltd., London

Larson, R. Secrets in the bedroom: adolescents’ private use of media. J Youth Adolesc; 1995; 24, 5 pp. 535-550. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01537055]

Larkin, RW. The Columbine legacy rampage shootings as political acts. Am Behav Sci; 2009; 52, 9 pp. 1309-1326. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764209332548]

Lasch C (1991) The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. London. WW Norton & Company

Lee, S; Scott, D; Kim, H. Celebrity fan involvement and destination perceptions. Ann Tour Res; 2008; 35, 3 pp. 809-832. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.06.003]

Levin J (2014) Mass murder in perspective: Guest editor's introduction. Homicide Stud 18(1):3–6

Maltby, J; Day, L; McCutcheon, LE; Houran, J; Ashe, D. Extreme celebrity worship, fantasy proneness and dissociation: developing the measurement and understanding of celebrity worship within a clinical personality context. Personality Individ Differ; 2006; 40, 2 pp. 273-283. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.004]

McKenzie, SK; Collings, S; Jenkin, G; River, J. Masculinity, social connectedness, and mental health: men’s diverse patterns of practice. Am J Mens Health; 2018; 12, 5 pp. 1247-1261. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1557988318772732]

Money, J. Lovemaps: Clinical concepts of sexual/erotic health and pathology, paraphilia, and gender transposition of childhood, adolescence and maturity; 1986; New York, Irvington:

Oksanen, A; Hawdon, J; Räsänen, P. Glamorizing rampage online: school shooting fan communities on youtube. Technol Soc; 2014; 39, pp. 55-67. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2014.08.001]

Parker R (2014) Serial Killer Groupies. New York. RJ Parker Publishing INC

Pleiss, MK; Feldhusen, JF. Mentors, role models, and heroes in the lives of gifted children. Educ Psychol; 1995; 30, 3 pp. 159-169. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3003_6]

Potter, WJ; Levine-Donnerstein, D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. J Appl Commun Res; 1999; 27, pp. 258-284. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00909889909365539]

Purcell, C; Arrigo, BA. The psychology of lust murder: paraphilia, sexual killing, and serial homicide; 2006; Academic Press:

Ramamoorthy P (2013) I have a crush on a criminal. Retrieved, on 01/09/2014, from http://m.thehindu.com/opinion/blogs/blog-by-the-way/article5038297.ece/

Riesman D (2001) The lonely crowd: A study of the changing American character. New Haven. Yale University Press

Rocque, M. Exploring school rampage shootings: research, theory, and policy. Soc Sci J; 2012; 49, 3 pp. 304-313. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2011.11.001]

Romano A (March, 2013) Tumblr’s creepy fascination with Ohio school shooter T.J Lane. Retrieved from http://www.dailydot.com/society/tumblr-tj-lane-ohio-school-shooter-fandom/

Rosenhan, DL. On being sane in insane places. Science; 1973; 179, 4070 pp. 250-258. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.179.4070.250]

Salmon, C; Symons, D. Warrior lovers: erotic fiction, evolution and female sexuality; 2003; Yale University Press:

Sharma, BR. Disorders of sexual preference and medicolegal issues thereof. Am J Forensic Med Pathol; 2003; 24, 3 pp. 277-282. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.paf.0000069503.21112.d2]

Simpson, JA; Gangestad, SW. Sociosexuality and romantic partner choice. J Pers; 1992; 60, pp. 31-51. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00264.x]

Slavikova, M; Panza, NR. Characteristics and personality styles of women who seek incarcerated men as romantic partners: survey results and directions for future research. Deviant Behav; 2014; 35, 11 pp. 885-902. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2014.897120]

Slotter, EB; Gardner, WL. The dangers of dating the “bad boy”(or girl): when does romantic desire encourage us to take on the negative qualities of potential partners?. J Exp Soc Psychol; 2012; 48, 5 pp. 1173-1178. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.05.007]

Stearns, SC. Life-history tactics: a review of the ideas. Q Rev Biol; 1976; 51, 1 pp. 3-47. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1086/409052]

Stearns, SC; Rodrigues, AM. On the use of “life history theory” in evolutionary psychology. Evol Hum Behav; 2020; 41, 6 pp. 474-485. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.02.001]

Steinberg L, Silverberg SB (1986) The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development 841–851

Stepchenkova, S; Zhan, F. Visual destination images of Peru: comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour Manag; 2013; 36, pp. 590-601. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.08.006]

Tein, JY; Coxe, S; Cham, H. Statistical power to detect the correct number of classes in latent profile analysis. Struct Equ Modeling; 2013; 20, 4 pp. 640-657. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.824781]

Tinbergen, N. On aims and methods of ethology. Z Tierpsychol; 1963; 20, 4 pp. 410-433. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1963.tb01161.x]

Tinbergen N, Perdeck AC (1950) On the stimulus situation releasing the begging response in the newly hatched herring gull chick (Larus argentatus argentatus Pont.). Behaviour 1–39

Tombs, S; Silverman, I. Pupillometry: a sexual selection approach. Evol Hum Behav; 2004; 25, 4 pp. 221-228. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.05.001]

Tooby J, Cosmides L (1992) The psychological foundations of culture. The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture 19

Trivers, RL. Campbell, B. Parental investment and sexual selection. Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971; 1972; Chicago, Aldine-Atheron: pp. 136-179.

Tuchakinsky R (2010) Para-romantic love and para-friendships: development and assessment of a multiple parasocial relationship scale. Am J Media Psychol 3(1/2):73–94

Van Leeuwen T, Jewitt C (eds) (2001) The handbook of visual analysis. London. Sage

Vermunt, JK; Magidson, J. Latent GOLD's user's guide; 2000; Boston, Statistical Innovations Inc:

Vitello C (2006) Hybristophilia: the love of criminals. Sex Crimes and Paraphilia. 197–206

Warren L (2012) ‘Holmies for life’: shocking pictures reveal sick online fans of Dark Knight massacre gunman James Holmes who wear his favourite clothes Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2181721/James-Holmes-fans-The-sick-online-fans-wear-plaid-drink-slurpees-support.html#ixzz3PwEJQbOH. July 2019

Woodworth, M; Freimuth, T; Hutton, EL; Carpenter, T; Agar, AD; Logan, M. High-risk sexual offenders: an examination of sexual fantasy, sexual paraphilia, psychopathy, and offence characteristics. Int J Law Psychiatry; 2013; 36, 2 pp. 144-156. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.01.007] Secret Service, National Threat Assessment Center

Zahavi, A. Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. J Theor Biol; 1975; 53, 1 pp. 205-214. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3]

Zhou, L; Whitla, P. How negative celebrity publicity influences consumer attitudes: the mediating role of moral reputation. J Bus Res; 2013; 66, 8 pp. 1013-1020. [DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.025]

Zinkhan GM, Shermohamad A (1986) Is other-directedness on the increase? An empirical test of Riesman’s theory of social character. J Consum Res 127–130