William S. Carlson

Greenland Lies North

Chapter 5: Balloons, Graves, and Glaciers

Chapter 7: Week-ending With Eskimos — Winter Tales to Max

Chapter 8: More Village Life — Winter Tales to Max Continued

Chapter 9: What the Well Dressed Eskimo Will Wear — Winter Tales to Max Continued

Chapter 10: Eskimo Ways and Means — Winter Tales to Max Continued

Chapter 11: While Night Approaches

Chapter 12: October Miscellany

Chapter 13: Eskimo and Dog Neighbors

Chapter 15: Of Radios and Kings

Chapter 19: Voyage to Augpilartok

Chapter 23: The Long Night Ends

Chapter 25: Toward Devil’s Thumb

[Front Matter]

[Publisher Advert]

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YOBK • BOSTON • CHICAGO

DALLAS > ATLANTA • SAN FBANCIKCO

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA

HADBAB • MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

OE CANADA, LIMITED

TOBONTO

[Title Page]

WILLIAM S. CARLSON

GREENLAND

LIES NORTH

ILLUSTRATIONS BY PHYLLIS WESLEY

NEW YORK

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1940

[Copyright]

Copyright, 1940, by

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

All rights reserved-no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

First Printing

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[Dedication]

TO

WILLIAM HERBERT HOBBS

Good Friend and Great Teacher

Contents

-

Voyagers

-

Godhavn

-

Arctic Coal

-

To Work!

-

Balloons, Graves, and Glaciers

-

Waiting for Winter

-

Week-Ending with Eskimos—Winter Tales to Max . 59

-

More Village Life

-

What the Well Dressed Eskimo Will Wear .... 79

-

Eskimo Ways and Means ............... 83

-

While Night Approaches................. 97

-

October Miscellany.............. no

-

Eskimo and Dog Neighbors . 119

-

Twilight.................. 132

-

Of Radios and Kings......... 149

-

The Long Night.................. 164

-

Beckoned North................. 180

-

Toughening Up.................. 193

-

Voyage to Augpilartok.................. 204

-

Vacationing............ 217

-

Last Efforts............ 230

-

Return..................... 232

-

The Long Night Ends........ 237

-

Northward Ho!................... 245

-

Toward Devil’s Thumb................. 259

-

Ramparts of the Ice Kingdom....... 268

-

Last Days............... 284

Appendix............. 291

Acknowledgments.......... 303

Glossary............... 305

Illustrations

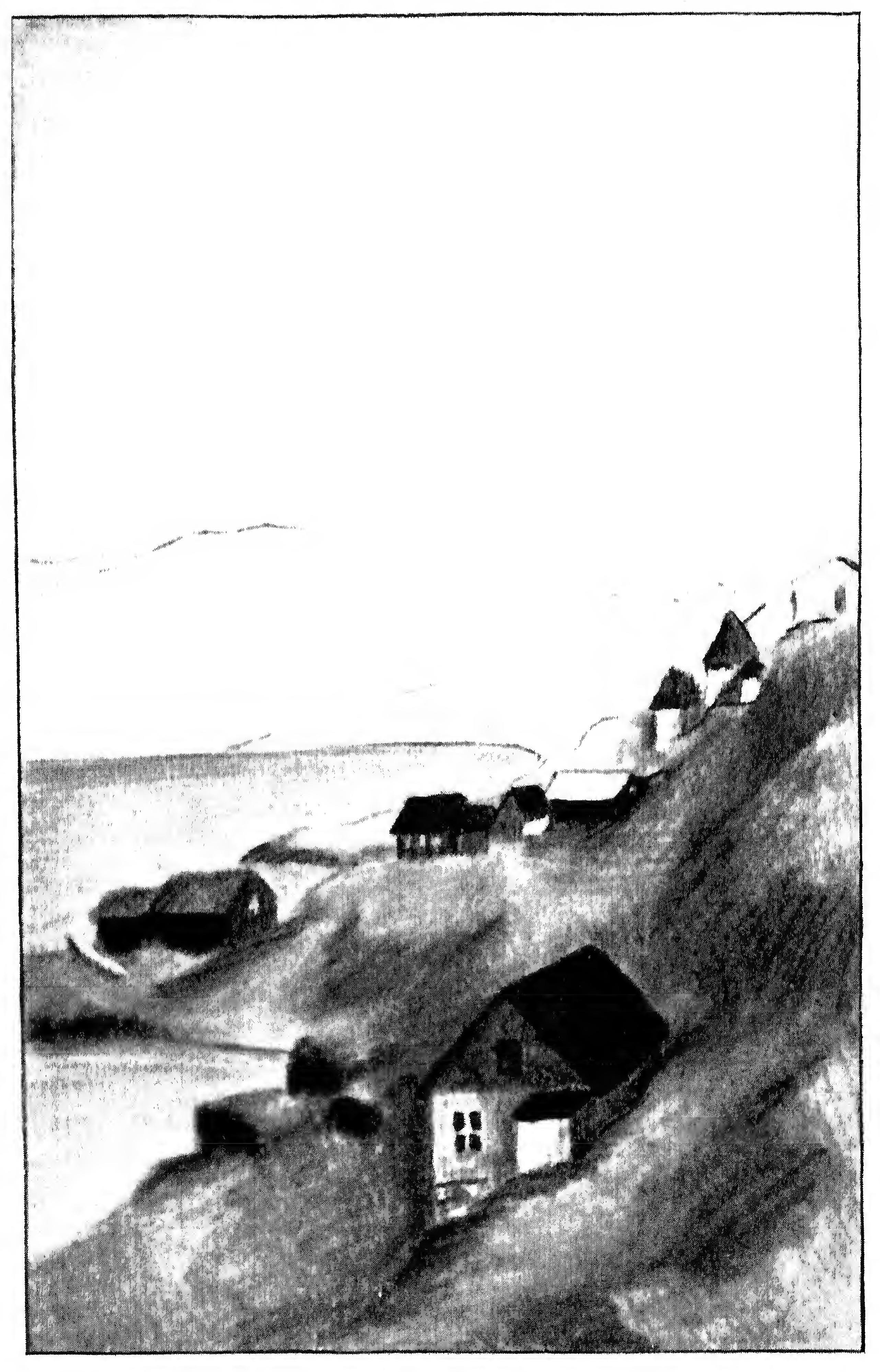

Village.................... 28

David Olsen........... 74

Gustaf..................... 88

Ewa.......... 122

Takamuak............ 158

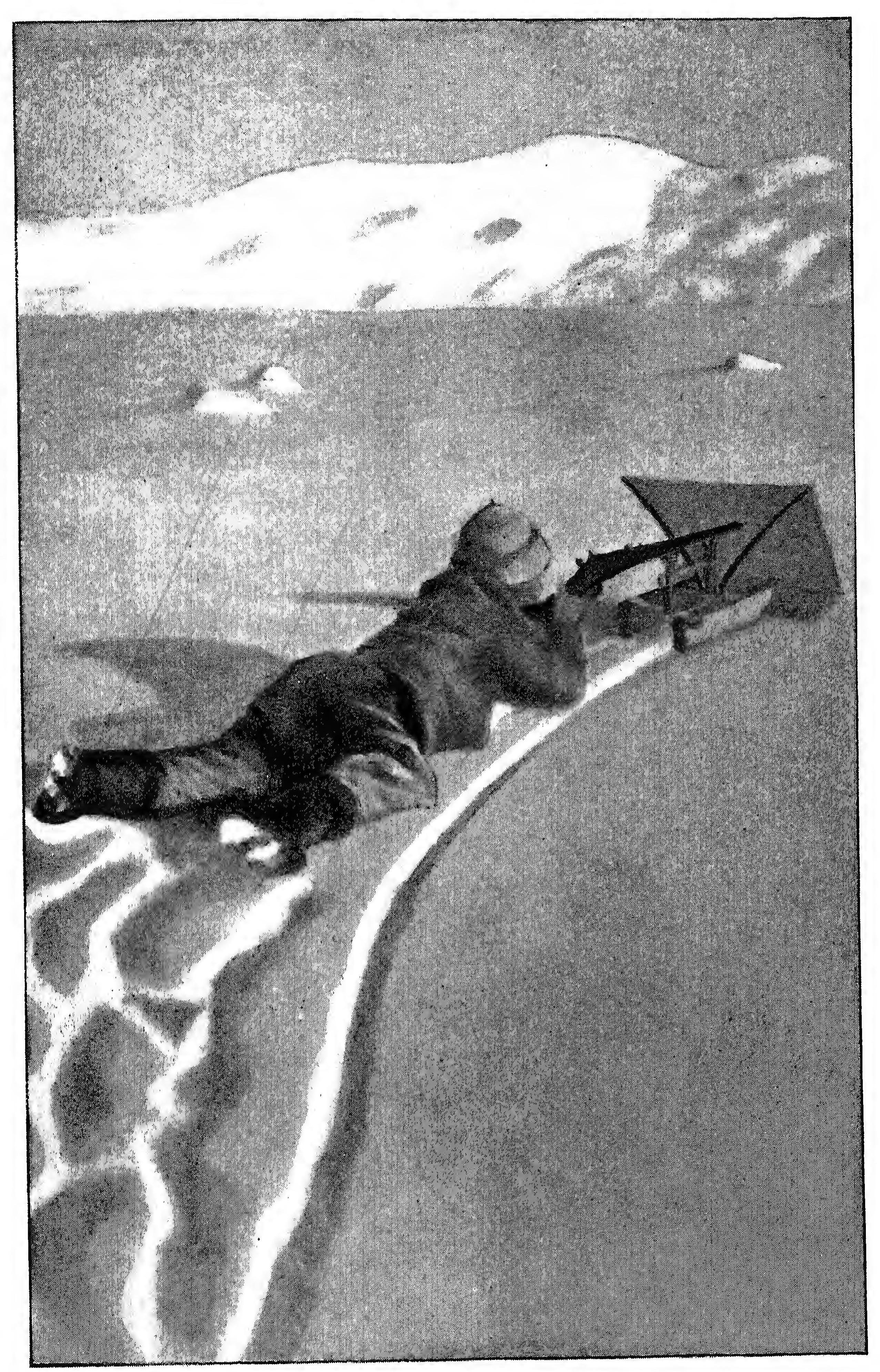

Utok Hunting................... 206

Susan.................... 238

Knud..................... 282

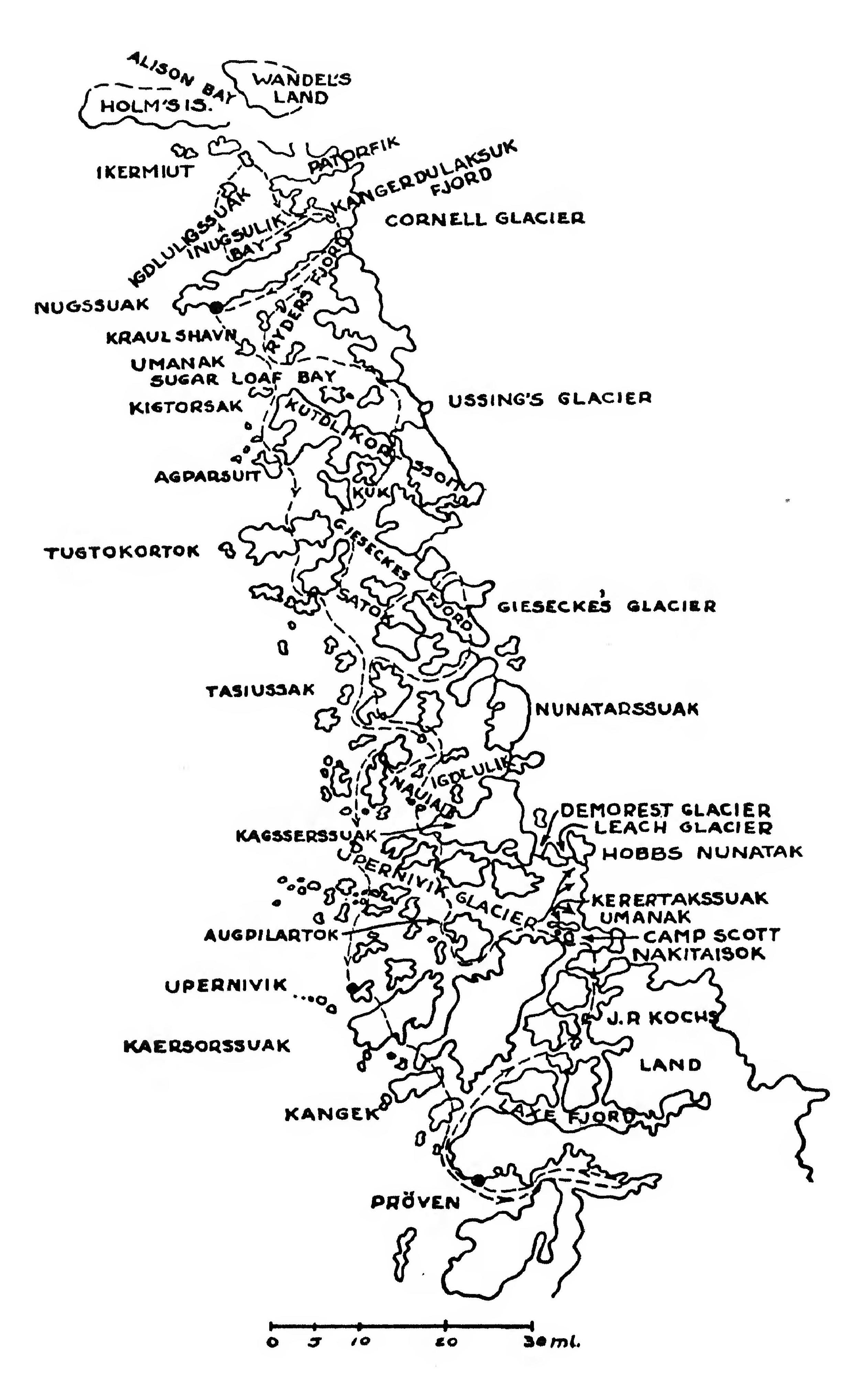

Maps

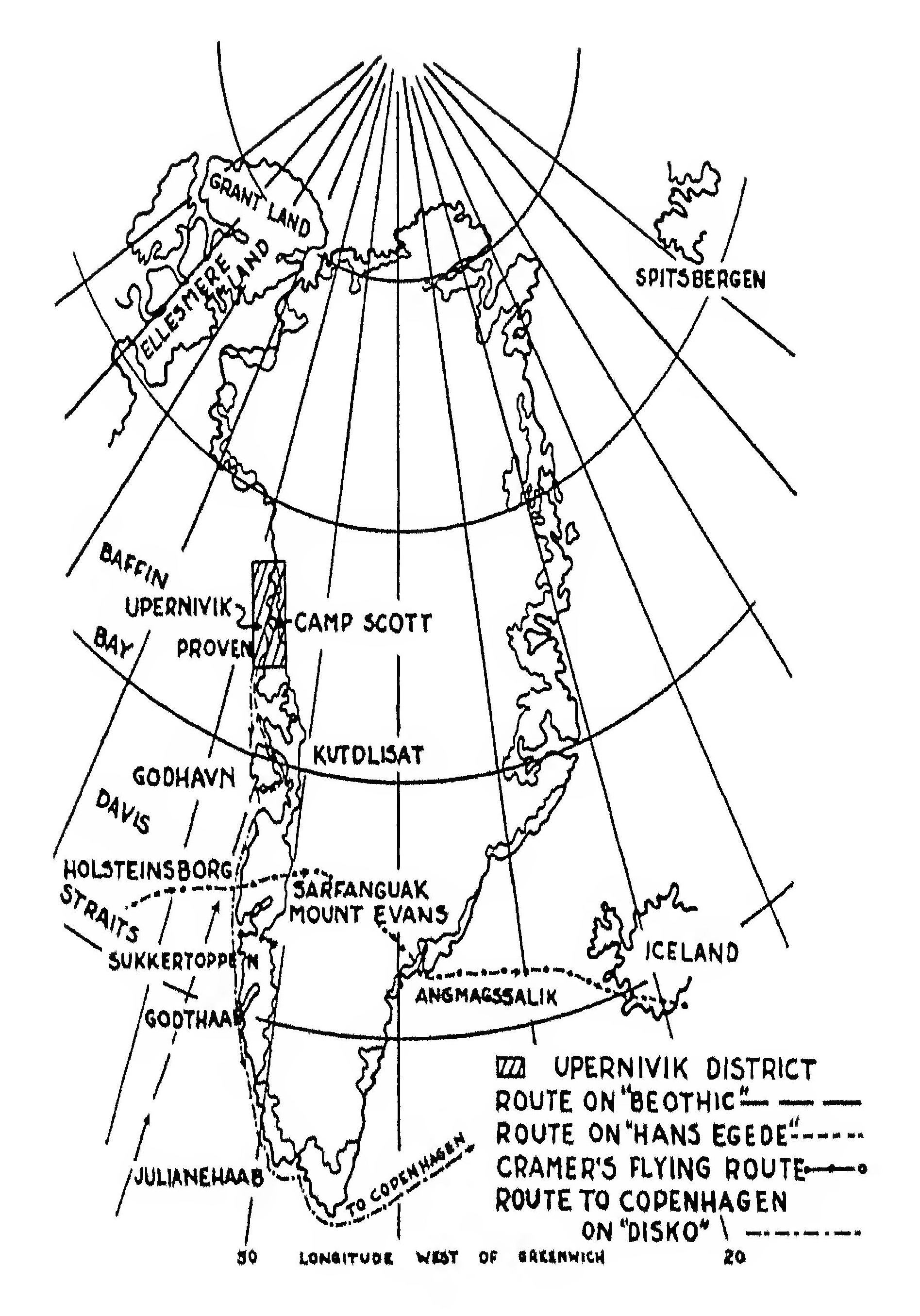

Greenland Showing Location of Upernivik District .. 3

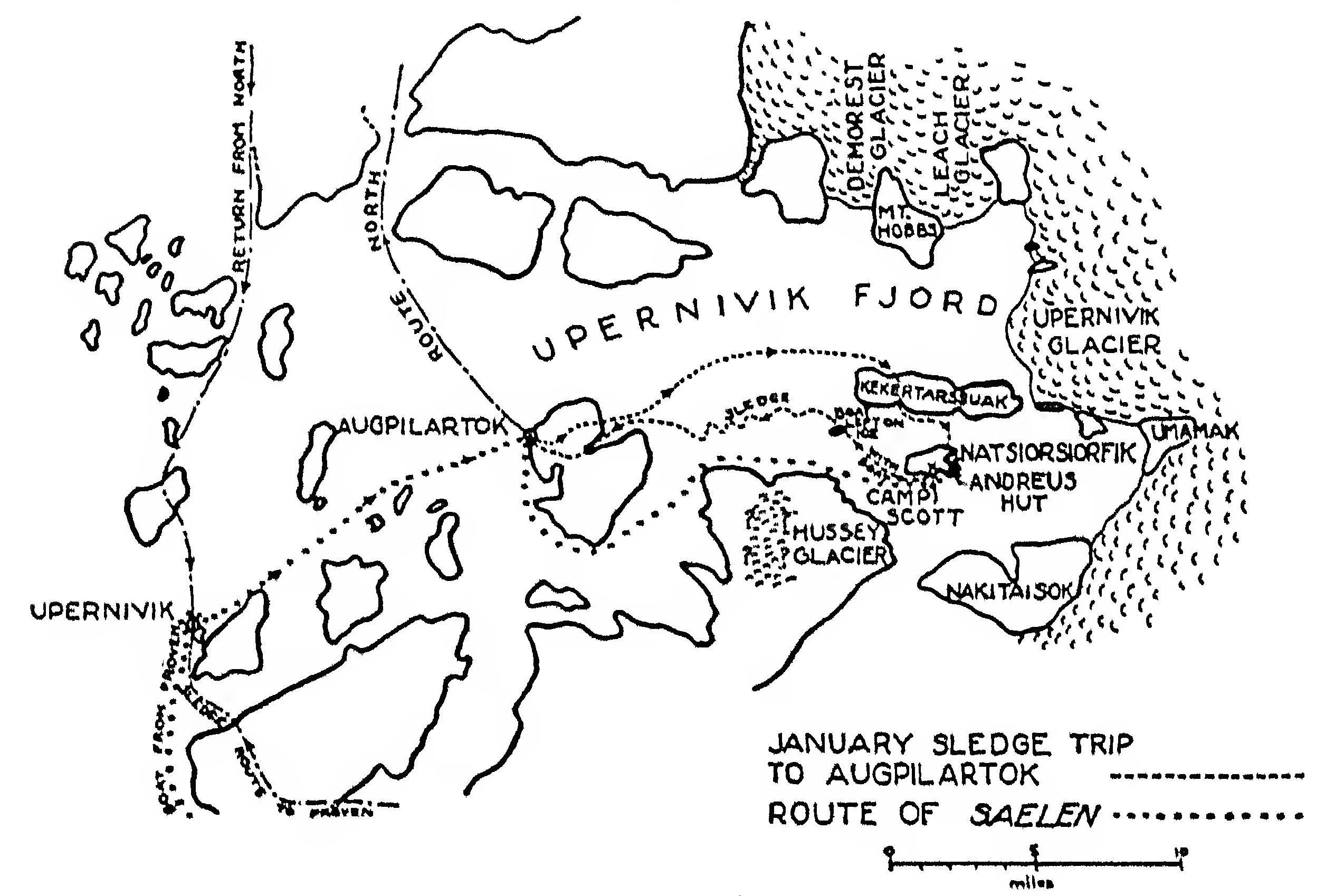

Camp Scott and Vicinity............... 35

Upernivik District Showing Route of Winter Sledge Journey ....... 247

Chapter I: Voyagers

JULY 31st, our last day in civilization. Weather clear and cool.

For the first time since the Beothic anchored in North Sydney harbor to take on supplies, her squat soot-caked smokestack belches forth smoke, which drifts away rapidly landward, a brown stain against the blue of the sky.

Within a few hours we start with the Beothic on her annual voyage to Arctic waters. Our expedition is on its way to establish a new station near Upernivik for the study of northland winter air currents. Having spent a year in Greenland, I survey the scene calmly. The rest of the expedition is beside itself with repressed excitement; he is Max Demorest, a University of Michigan undergraduate, for whom all this is a novel experience not quite to be believed. He stares incredulously around the decks, where a whole barnyard of domestic animals is scrambled promiscuously with hatch covers, winches, barrels, lumber, an assortment of boxes, ten Canadian Royal Mounties in scarlet full-dress uniforms, a student of Eskimo pathology, two artists engaged by the government, an explorer-botanist, and his small granddaughter—not to mention the little vessel’s harassed crew which labors between despair and heroism in making ready for the North Atlantic.

It is a heady setting for our start. When at last the bow dips gently under us, then thrustingly into the incoming swells as we point out to sea, I breathe deep of the stinging air. I tell myself it is pure satisfaction that I feel, but my thoughts are confused. Six months have flown by in the excitement and haste of preparation, and now, for the first time, I have a chance to think; indeed, must think. New York nine hundred miles away. The shores of Nova Scotia, ebbing behind us, in a few weeks more to be two thousand miles distant. Then, Max and I alone on the edge of the Greenland icecap.

I think of the stores of food and lumber in the hold, of the clothing, the scientific instruments, the other equipment prepared for us, and weigh them against a winter on the edge of the icecap....

“Dreaming of that cozy station beside the Ice Box?”

This question, accompanied by a jovial thump on the back, jerked me up and cut short my daydreams. I grinned rather sheepishly at Inspector Joy of the Mounties, and began pacing the decks with him.

Inspector Joy and his troop were to prove excellent companions, which was fortunate, as Max and I shared their quarters on the after deck. These men were replacing others whose two years of solitude in outposts on lonely Baffin and Ellesmere islands were at an end. Max and I never ceased to marvel at—and secretly envy— the unemotional manner in which they looked forward to their vigils. If ever there was a group of unsung heroes, these casual Mounties must be among the most laconic! Not that they were silent as to the hardships of the North. We heard many lurid tales, most of which probably were true, for it was only when they came to refer to their own experiences that their speech dried up.

We never did learn very much about the Inspector’s own thirteen-hundred-mile sledge journey, one of the longest on record. What a feat it was can be guessed by one episode. Joy and his companion had just completed a temporary snow house, and had gone into it, leaving their firearms outside, when a bear caved the roof in on top of them, increasing their number to that of the proverbial “crowd”! Through quick thinking and quicker action, the visitor was diverted, the weapons reached, and an end put to the “incident.”

Presently we all retired to a sort of spare pilot house built for us on the after deck. The Beothic had been constructed by the United States Government during the World War—one of the old “one-hundred-day” boats—and her sleeping quarters were limited; hence the addition of the Chateau-on-the-After-Deck, or Rampasture as it was known in our lighter moments. Admission was by a password not to be repeated here. The interior proved stark but crowded. Four all-purpose tables, on which boots and belts were being polished much of the time, occupied most of the floorspace. The walls were lined by an even dozen double-decker bunks. Baggage was put under the bunks.

In the cramped space there was remarkably little confusion, though much noise. When that died down a little, lots were drawn for bunks—I secured a lower, with Max over me. Then, in almost perfect unison, off came twelve pairs of shoes, twelve pairs of trousers, twelve shirts; and, race as I might, the Mounties had all turned in before me!

I stretched out arms and legs, blissfully tired. This was the life! The dip and sway of my berth lulled tense nerves while it stimulated imagination pleasantly. Above the mild hiss and slap of waves outside the open port there came to my ears an argument between two of the Mounties as to the relative advantages of snow rub and warm-water rub for relieving frostbite. I was still undecided whether cold or warm friction was to have the better of it, when the solid comfort of my berth lulled me to sleep.

The next morning I awoke to a hubbub of voices in a foreign tongue. For a moment I could not imagine to what land or situations I had been transported. Then my sleepy eyes took in the bare woodwork of walls and tiered bunks, and saw the French-speaking Mounties in all stages of dress, some already polishing their apparel, others, like Max and myself, still yawning rebelliously; I felt the motion of the ship under me, and I realized that I was on the way to my wintry station beside the great Greenland icecap. With a shiver, I arose.

A dash, of cold water on the face gave me die energy for a brisk walk around deck. Then I was ready for breakfast.

The Mounties by that time had had their breakfast, and Captain Falk of the Beothic and Inspector Joy alone awaited me at the long table for fifteen. This was the regular arrangement for meals. While stewed fruit, pancakes, and coffee were disappearing, I spent a pleasant hour listening to the Captain and Inspector Joy. The latter, I found, was a “brother under the parka skins,” for he had had his share of the same ferocious foehn wind that had rendered my previous Arctic stay so memorable. The blow, he told me, had shot pebbles through window panes at such speed as to cut clean bullet holes! Joy had an inexhaustible fund of such North Country lore. Nor were Captain Falk’s sea experiences less interesting. However, what impressed me most about him was that he did not accept a single hot dish from the steward. This in a man accustomed to voyaging in Arctic waters!

When Captain Falk became aware of my curiosity, he admitted that it was a rule with him never to eat any but cool dishes. Woe to the careless doughboy who so much as served a cup of hot coffee! It was resented as an attempt to poison him, for, reasoned the worthy salt, individuals who eat meals hot become “wormy” —he had once been, himself! For years he had suffered, and the best medical aid in North Sydney had been helpless to relieve him. Succor came finally in the form of advice from a retired midwife, who pointed out that worms were conquering him before the end of his allotted span, and explained the reason why. The Captain never erred again. He warned us gravely to follow his example, and seemed grieved when we did no more than promise to think the matter over.

That day, and the next also, the weather remained fine. The Beothic passed the narrow Straits of Belle isle, with towering cliffs on either hand, left Cape Baird behind, and continued “down North” along the 55th meridian. The rugged coast of Labrador, our almost constant companion, we saw for the last time. The open sea surrounded us. We should not see land again until Greenland was reached.

The fourth day it began to blow. When we came up the companionway it was necessary to grasp the rail. A choppy sea flecked with whitecaps greeted our eyes, and even as we watched the waves grew and the rolling of the ship increased to distressing proportions. The full strength of the storm descended on us. At intervals, heavy waves crashed over the side to thunder against the battened-down hatches. Every lurching dip flushed the after well scuppers with a torrent of racing, foaming water, and the livestock marooned aft cried out hysterically, like a chorus.

Captain Falk could scarcely be induced to leave the bridge. He gave orders for all passengers to stay below, where the close confinement added to our discomfort of mind and body. It was like being jolted along a mountain road in a wagon-borne shut coffin. For the first time our ravenous sea appetites were affected, and the evening cocoa and sandwiches ignored. We came to avoid looking at one another. Dr. Porsild, the explorer-botanist, alone remained unmoved, lecturing away calmly on the history, political organization, and economic problems of Greenland to a wincing, ever-shrinking audience.

That night our sleep was broken. I recall dreaming fitfully of being swung round faster and faster in the swaying, dipping scat of a Ferris wheel, Dr. Porsild at the controls adamant against my pleas for mercy; and between times, in a dreamy stupor, I longed for the approach of daylight.

But dawn brought no comfort. The storm was battering us with heightened violence. Racks were put on the messroom table, and we sought with weary hands and elbows to hold down as many dishes as possible, unsuccessfully. No one cared. Max confided afterward that he was glad to see his coffee spurt across the cloth and his eggs slither after it. It was an excuse not to eat. As for me, the little food I managed to down seemed to follow with embarrassing sympathy the antics of the food on the table.

The entire well deck was now awash. As the Beothic wallowed in the ponderous seas, tons of water were sent swirling through winches and loading booms to crash with stunning violence against the opposite rail. To maintain footing was next to impossible. The water that filled the well deck swished back and forth as though the Beothic were a cocktail shaker in the hands of some indolent Gargantua.

Instead of climbing monkeylike over hatches as did everyone else, Max Demorest elected to go aft along the well deck itself! Maybe Max had been roused to fighting mood by the “roughing” of the sea. We shouted warnings when we saw what he was about, but it was too late to be of use, too late even for him to turn. He could only go on. We looked at that churning water, and we looked at Max, cautiously progressing. I felt suffocated, as though I were lying under the water where Max might soon be. But all was going well; he had timed his attempt perfectly. He was no more than ten feet from reaching the quarter deck when the rail went under.

Where he had stood beside the rail an enormous wave greened against the ship. We could see nothing but water, and the tops of the loading gear, meeting each other at an acute angle. Then, after moments of sick agony, the Beothic heaved over painfully under us, the watery mountain leveled off the deck, and a thoroughly, chastened Max rose into view, choking for air, and clutching desperately at a coil of rope.

No word was spoken when we hauled him up the after-deck stairs.

Next, one of the pigs marooned on the after hatch took it into his fat head to break loose from his crate and enjoy a plunge into the swirling lake of the well deck. Shocking squeals of terror rent the air and tore at our ears. It was almost more sickening than the suspense of Max’s immersion. I looked at him. He looked away. Then Margots of the Mounties went out to Get His Pig, crawling from quarter deck to after hatch and from there to a stalwart winch, waiting for the swimmer to be washed his way. Luck was with the pig. But not for long. The seagoing Mounty had just grabbed him and started cautiously for safety when another wave plucked the slippery burden from under his arm. Mountics arc hard to discourage, however. A second time Margots found the porker within reach, and this time, with a toehold on the starboard stern side, he splashed his way successfully back to the crate.

“Worth his weight in gold here,” he beamed, smacking his lips, as he returned to his bunk to change.

There followed a hot argument as to whether the pig ought to be rolled over a barrel to get the water out. The argument came to an end only when someone asked how you could roll one barrel over another.

The third morning of the storm still saw heavy seas running, yet the worst was over. Max reappeared on deck and perched himself on the foe’s’le head. He had been there about an hour when he shouted, in chorus with the lookout, “Iceberg ahead!”

We all rushed to the bow. There, several miles away, but looking much nearer in the crystal-pure atmosphere, and glaring in the morning sun as though illumined from within, a block of ice the size of an apartment house rose like a frosted volcanic isle in our path. Already the quartermaster had given the Beothic the wheel, veering her so that we would pass to port of the berg.

“Looks like it’s from the Antarctic,” muttered Max, puzzled by the regular shape. Arctic bergs are seldom tabular, though certain Greenland glaciers send off ice as cubistic as any to be found off Antarctica.

As we passed wide to avoid treacherous submerged shelves, the sides of the berg rose sheer and smooth and white from the surface of the pale green water to the height of the Beothic’s smokestack.

This was an exceptionally large mass to be encountered so far south at that season, but we were soon to see many more, and during the spring thaw behold them breaking off from the parent glacier to sidle away south on a journey that was to end, perhaps, at the Gulf Stream—if the United States Coast Patrol did not first dynamite them for fear of injury to transatlantic shipping.

It was now August 6th. Since our departure from North Sydney harbor the thermometer had been dropping steadily. We had progressed in a few days from the scorching pavements of New York to a region where a heat wave meant an early afternoon temperature of 450 Fahrenheit, and where keeping a fire lighted in the main cabin was a necessity. From noon on, glimpses of the Greenland coast showed through the thick curtains of fog. It was very quiet. Jagged peaks, occasional half-guessed-at cones of snow, and great rocky headlands unrolled against a dull sky like a moving stage panorama unaccompanied by sound. Presently the wind, too, died down, leaving the sea calm save for the slow ground swells. I think we all felt that we had entered a different world. Max lost much of his exuberance, and I stared away ahead wondering what pale Greenland had in store for us.

The distant passage of a ship during the afternoon was a welcome distraction from our funereal progress. The omniscient Dr. Porsild declared it a 10,000-tonner—probably the Arctic Prince or the Arctic Queen—large vessels used to supply trawlers working along the Greenland coast with coal, fresh water, even doctors and operating facilities. At one time we counted no fewer than fourteen of the dependent power trawlers. Sailing vessels are seldom seen now on the fishing banks, as they are less reliable.

The waters into which we were moving were full of icebergs and growlers, and the Beothic proceeded cautiously through the fog, sounding the boat’s whistle three and four times an hour to determine by echo the location of the most formidable bergs. From time to time there would be dull thuds and scraping as floating ice bumped along the iron-plated sides of our little ship.

These noises worked on us strangely. The melancholy whistling, the thud and grind of ice alongside, only emphasized the enveloping silence, and combined with the dull vapors in the air and our sense of nearing the hardships and solitude of our northern post to depress us beyond our powers of concealment. Perhaps we should have felt it less if we had not been compelled to remain inactive. But there was little to do beyond futile rechecking of stores, and I, for one, was glad when night came and offered the refuge of sleep.

Our last evening aboard was welcomed as the end of “a trial.” It signaled the departure next morning of Dr. Porsild and his granddaughter, also, and marked as well the birthday of James Richards, assistant to the director of the Beothic s expedition. It was Jim’s first birthday north of the Arctic Circle, and a celebration was called for. After much mysterious preparation the steward admitted us to the main cabin. There on the center table stood an elaborate birthday cake, suitably inscribed, and flanked with bowls of fruit punch laced with whisky! An excited murmur of laughter and jokes broke out, as we hastened to forget our constraint. Toasts were drunk, amidst cheers, to the guest of honor, and in turn to every passenger about to leave ship. Dr. Porsild replied fittingly, and Max and I attempted to follow suit. Then followed a variety of entertainment. An amateur magician among our number amused us with successful sleight-of-hand tricks, and still more with others that we saw through without much difficulty. Jim Richards furnished us with the last edition of his typewritten daily newspaper—one of the high lights of our trip—and as his items went the round of our company, roars of laughter were leveled at the amused but helpless victims of his witticisms. When the excitement died down, the remainder of the evening was spent in “yarning” before the fire. As usual, grisly tales predominated. One particularly choice narrative was told of a Mounty who took his young wife north with him. In that lonely situation she became very fond of the sled dogs, feeding and petting them daily until she became a favorite with them. She continued that until she slipped and fell one day and was chewed to death.

In the morning a strong westerly wind lifted the fog curtain, revealing the Greenland scene in all its severity. The great central ice plateau was a gray glitter in the distance. Nearer were ranges of mountains, less high than those in the interior, and merging in turn with the narrow strip of comparative flatland along the coast, whereon dun-colored Eskimo settlements were sparsely scattered. Existence for these people is impossible in the bleak interior. The Eskimos’ way of life depends upon maintaining contact with the sea, which for them is highway, and food reservoir, and general supply house. The shore line itself was rugged with rocky islets, low islands, steep-walled fjords and bold, jutting cliffs. Suddenly the Beothic seemed the very essence of civilized luxury.

Despite the striking appearance of the coast, my eyes turned always and unconsciously toward the interior, where the immense flattened dome of eternal ice mountain-thick dominates the whole island which is Greenland. That icy interior is one of the most intensely cold regions in the northern hemisphere. It is as much colder than the North Pole as Montreal is than Miami, Florida. Air coming in contact with the ice of that desolate expanse is chilled still more, and because of the dome shape of the plateau, slides down toward the margin as does a dense volcanic cloud down the side of its parent mountain. The sliding of the frigid air is further accelerated as it nears the sharper inclines toward the sea. Sometimes explorers traveling inland meet with hurricane blizzards of this origin. Almost as dreadful as liquid fire is this life-withering blast of frozen air and sleet hurled in torrents of 120-mile-an-hpur velocity. Well is Greenland named the storm center of Earth’s northern half!

The camp Max and I were to pitch beside the icecap would have to be a snug one.

Chapter 2: Godhavn

AGAINST the harsh background of the land there came into view a huddle of European buildings. The Beothic slowed, coasted idly, then dropped anchor opposite the coal bunkers conspicuous on the waterfront. Our voyage was over.

Kayaks began paddling out to us by ones and twos, while from Godhavn town the curious trickled down to form a puddle of humanity on the wharf, hands waving in response to our greetings. Presently a motorboat coughed hopefully. Our eyes turned,” toward a landing-dock where a small-boat was illumined by a glory of brass buttons, epaulets and sword hilt.

“The Governor!”

I straightened my clothes and prepared my request. The director of the Beothics expedition had offered to take us on to Upernivik instead of dropping us at Godhavn as had been originally planned, and now I had to request the formality of the Governor’s consent.

Aboard he came in all his majesty and, having welcomed us, declared he had no authority to allow the change.

“But it would save us two weeks!” I protested, thunderstruck. Two weeks of Godhavn, not to mention board bills, instead of one more pleasant day on the Beothic, and all because in the correspondence between the American and Danish departments of state, it had been arranged that the ship Disko was to pick us up! “Why, the Disko doesn’t leave Copenhagen for three days yet!”

But red tape is no more elastic for being north of the Arctic Circle.

Inspiration struck me. “Can’t you radio Copenhagen before the Beothic sails?”

Unfortunately, no. And with a polite bow the Governor, unquestioned master of the deck, retired to his launch.

It was with ill grace that we proceeded to unload our baggage, lumber, and gear, and store the whole in a waterfront warehouse. It increased our disappointment to know that the weather was ideal for home-building. Delayed two weeks, we might have to perform that arduous task under the torrent of autumn rains— sheer torture even to contemplate. No wonder that on our last return to the ship Inspector Joy took one look at us, and then herded us into a cabin to drink a few healths with him! Others joined the party to help console us. By the time the Beothic was ready to up-anchor, we understood sympathetically that the Governor’s very remoteness from civilization made official correctness all the more necessary. Dear old Gov’nor! Noble soul! Then we piled into a sealskin boat already filled with Eskimos. When informed that this was an umiak—a woman’s boat—Max grew indignant, almost forgetting to wave farewell when we landed.

Out of nowhere the Governor appeared to escort us to the house at which we were to be guests during our stay. The owner, Johannes Olsen, was director of a magnetic survey being conducted in that part of Greenland, a pleasant, witty scholar, master of excellent French and English. Though his wife spoke neither language, she, too, proved an amiable person. Four small children, in addition to Max and me, completed the cheerful household— cheerful, that is, after that night, for just then Max and I were sorry company. Having apologized for being such unsatisfactory guests, we went to bed with the greatest pleasure.

The next morning, refreshed by sleep, I observed with interest the construction and furnishings of the Olsen house. Built to resist the Arctic storms and painted the typical red and white of all

government buildings, outwardly the house had little to commend it architecturally. Inside, however, Mrs. Olsen had managed to contrive a bit of Denmark. The furnishings were typical of a house in the old country with its curtained windows, feather bedquilts, iron-posted beds, hothouse flowers, rugs on the floor, and a china cabinet filled with Dresden porcelain. Only the scene through my bedroom windows belied the surroundings. On one side icebergs loomed in the calm blue waters of Disko Bay; on the other the imposing basalt cliffs of Disko Island reaching heavenward toward a summer sky streaked with soft, pastel colors.

I waited until nearly noon to make sure I should not disturb the Governor in bed. Then I called on him, determined to see whether some of the official red tape might not be unwound. The Governor received me in his office, decorated with the oil paintings of a former local Danish official who was an amateur artist. In the haze of good cigar smoke, His Excellency mellowed, grew cordial, gave me a map of Greenland as well as valuable advice based on his acquaintance with the Upernivik district, and even granted permission for us to sail north on the first boat to arrive from Copenhagen! I congratulated myself on my superior discernment of character the day before when restored to normalcy by the healths drunk in the Beothics cabin. Decidedly, my visit had been a success.

I hurried briskly toward the radio station, quite a little elated by the cleverness of my maneuvers and by the crisp air. A short stay in Godhavn might not be at all a bad thing!

The radio operator disposed of my messages in short order. A jovial chap, Poulsen, insisted that I remain to take coffee with him and his agreeable wife—all Greenland Danes somehow seem fortunate in their marriages—and we were deep in exchange of reminiscences when an excited Eskimo small boy burst in. Arfangniaq! Arfangniaq! A whale had just been towed in by a government whaler, and the Eskimos were getting ready to flense it.

Poulsen hurried me out to view the spectacle. As we joined the crowd streaming down toward the sea, I was told: Sixteen species of whales known in Greenland waters. Hurry! All but three species summer visitors from the Atlantic. The whaler had once been a Danish destroyer. It makes a practice of towing its catch to the nearest sizable Eskimo colony. Hurry! Hurry! A whale means plenty for all. The Eskimos are given the meat in payment for stripping the blubber, which is sent salted to Copenhagen, manufactured into oils. Behold the whale!

People were streaming from all directions toward the shore where the seventy-five-foot whale was being dragged upon the rocks. Everyone seemed to know where to go. A group of urchins kept the yapping dogs at bay with stones; some men were pulling on tow lines; others were sharpening implements; the women were preparing for their tasks; like the crew of a circus, everyone knew his job and the time to do it. Finally, when the great beast’s tail was high on the rocks and only its huge head lay in the water, a half-dozen butchers climbed upon the corrugated back to start the flensing operations. With razor-sharp spears they went about their work with the zeal, dispatch, and care of a great surgeon. The freely flowing blood was carried off by a bucket parade to be cooked, and the surplus was slowly turning the water crimson. The expert dissection progressed from the tail toward the head. The blubber was cut into squares with slits for grappling hooks with which the chunks were dragged up the rocks to long wooden tables that had been set up. Here the women were busy salting the blubber and packing it into barrels.

Where the blubber had been removed others were cutting off the red meat and stacking it on the rocks. Little boys who were not busy with dogs scurried under the feet of their elders and with pocketknives sliced chunks of raw meat. Everyone seemed to enjoy the carnage; everyone was smeared with blood; and everyone was busy chewing the red meat and delicious matak (hide).

We could no longer restrain ourselves; the mass psychology of the crowd overcame us, and soon we had changed from interested spectators to enthusiastic participants. The meat was tough, but the matak was palatable. It tastes like peanuts and chews like rubber—a delicacy for a king! When filled beyond endurance, Max and I left the hilarious festival for a near-by hilltop where we stretched out to doze in the warm sun. Thus ended our first whale party!

The third morning of our stay, a messenger arrived with an invitation for me to call on Dr. Porsild, our scholarly shipmate of the Beothic voyage. I hastened to accept. Having knocked at the door of the Arctic station, a huge rambling structure a quarter of a mile from the colony, I was greeted by a native servant who ushered me into the vestibule. Dr. Porsild appeared almost immediately. After the usual formalities, and mutual questions as to plans, he showed me through the Arctic station.

“This,” said Dr. Porsild, “is my library.”

I stared about the twenty-five-by-forty-foot room, lined like a modem library with stacks of books of all descriptions. “It must be the largest one in Greenland!”

He smiled, and told me to browse around. I did so with increasing wonder as I came across books on exploration in Danish, English, German, French, Swedish, and Norwegian. There could be few works on matters Arctic or Antarctic not represented there in that remote Godhavn library. The collection seemed all the more remarkable because Dr. Porsild was so much of the time isolated from the rest of the world. Gratefully I accepted his offer to use the library as much as I desired, and came away at last laden with invaluable books and pamphlets, including a survey of the district where Max and I were to winter when we left civilization behind.

Godhavn is the most important settlement in North Greenland. A monthly newspaper in the native tongue, Greenland’s only newspaper, is printed there, and in addition to Dr. Porsild’s Arctic station there are Olsen’s magnetic station, a stone archives building, a wireless station, numerous other official buildings—one might almost include in this category the great coal bunkers on the waterfront—hundreds of houses and Eskimo sod huts, and a long, low church which was Max’s particular joy. Rows of metal cuspidors, one strategically placed beneath the pulpit itself, were, I hesitate to say, the attraction. Greenlanders are among the most inveterate of tobacco users.

The chief entertainment in Godhavn was tea and coffee drinking. My experience with radio operator Poulsen was but a hint as to what was to come. Wherever we went, alone or in company, Max and I were offered tea, tea, tea, or coffee and more coffee, the hospitable Godhavners never tiring of the hot drinks which are so vital a luxury in the Northland. Tea and coffee might well be termed the local medium of social exchange, relieving the monotony of routine existence. Of course, “society” is quite haphazard. For instance, the Olsens, Max, and I decided to “drop in” on His Excellency, the Governor. We marched into the hall, took off hats and coats, and delegated someone to tap on the livingroom door. No answer. The correct thing now was to search for the missing owner. We found him in his garden, where proudly he displayed hotbeds, modem chicken coops, and radishes, turnips, and lettuce of a very good size for Greenland. I felt a little confused at the discrepancy between this shirt-sleeve informality and the Governor’s extreme official dignity. However, I was able to console myself with the feast the Governor’s lady created impromptu, with wine added to the more customary beverages.

The morning after I visited Dr. Porsild there was much excitement among Danes and Eskimos alike. A second whale was being towed ashore, and as though that were not cause enough for celebration there steamed into the harbor, shortly after, a gray yacht of a cruiser! The Ville d’Ys of the French navy. The graceful ship from the romantic-sounding South brought to mind thoughts of another world, contrasting strangely with our present bleak surroundings. What could the vessel be doing here? Already I experienced the exaggerated curiosity of the colonial.

Presently the captain came ashore officially dressed in tricornered Napoleon hat, epaulets and buttons, long coat and sword, to pay his respects to the Governor. Max and I could not tell which exotic-looking dignitary enjoyed the ceremony the more. Provoking as the scene was to midwestern risibilities, we could see that these men represented their countries in all earnestness, making it a point of honor not to lessen formalities established under such different circumstances.

When the captain withdrew with the Governor I approached the crew of his gig. It was a pleasant surprise to find my doubtful French readily understood. Warmed by success, I concealed my astonishment and sat down to ask questions.

What was the Ville d’Ys doing here? The contre-maitre thrust his pipe stem at the waterfront coal bunkers. “We clean furnaces, we refuel,” he drawled.

“But why Greenland? Or is that a naval secret?”

The sailors smiled at one another. One fellow of Mediterranean swarthiness replied, “It is a secret, but we will let you in on it, m’sieur. The Ville d’Ys looks after the many French trawlers on the Greenland fishing banks.”

Despite my hesitant French I learned that the crew numbered one hundred and twenty-five, that they had been in Greenland water all summer, and that they were soon leaving for Halifax. Members of the crew came from all parts of France, the contre-maitre from Bordeaux.

“And you, m’sieur,” asked the contre-maitre, “where arc you from? New York?”

I shook my head.

“Ah, Boss-tone, then.”

“No, not Boston either. I’m from Detroit.” He looked blank.

“Detroit is a city east of Chicago.” When he still showed no sign of recognition, I asked in desperation what American cities he had heard of before.

“Oh,” said he, relieved, “Montreal.”

I gazed around at our Eskimo audience and wondered whether they could not do better in an American geography test. Nevertheless, the gig’s crew were fine intelligent fellows, and had they not been such thorough seamen, I am sure they would have heard of Automobile City.

I made the acquaintance of their captain the next morning. His round of calls had brought him to our hosts, the Olsens, and we spent a pleasant two hours in his company. This time the conversation was in English, which the captain spoke very well. Max afterwards agreed with me that the captain was the perfect example of the Frenchman met with the world over in official or military life, a gentleman devoted to his country and to his profession. Not even Max’s insistence in asking about a mystery ship reputedly a-building could make him less a gentleman—or less discreet. Though he would not deny the vessel’s existence, he put off questions with so much skill and tact that we could learn nothing.

Coaling the Ville d’Ys held the spotlight until the arrival of still another whale. This was a profitable, busy week for the Greenlanders, and a happy one for the dogs. Max and I contented ourselves with taking snapshots of everything and with awaiting the dance to be held that night, at which Danes, sailors, and Eskimos would be present. Eskimo girls in their fanciest anoraks (shirtblouses) and Sunday-best kamiks (skin boots) kept passing our home for hours before the festivities began. It was the Grand Ball for those north of the Arctic Circle.

The carpenter shop in which the ball was held was jammed early with all the villagers. Only a small space, no larger than a modem night-club floor, was left for the fun makers. There were two girls to every man, and the girls without escorts crowded the doorway, preventing extrance and exit once the dance began. Seated on a window sill in the far end of the room was an especially clever member of the group playing a wheezy accordion. The music he urged out of the concertina had the sameness of the tone reels of the Scottish whalers. Several times the concertina changed hands—sometimes for better, sometimes for worse—but the tune never. The sailors and native girls were prepared for anything; there were no collars to wilt and no flimsy dresses to tear. The girls wore sealskin shorts, bright-colored blouses with beautiful beaded collars over their shoulders, silk sashes, and purple skin boots topped above the knee with a black dogskin band.

From the row of girls standing along the wall I chose one and walked across the floor to her. She squealed, whether from embarrassment or from delight I have never known; but we whirled across the floor. Four steps forward, four steps back; whirl, whirl, whirl!

We danced until my feet blistered and my shirt was wringing-wet. The interior of the cramped building with its narrow door and sealed windows became a steamy mist. Then at last the dance came to an end, and Max and I went home and to bed. But it was still light, and for a long time I lay watching the groups of sailors and girls divide into pairs. Through the open window I listened to the echoing in the hills of the laughing voices of lovers.

It was a sad day for all when the coal bunkers of the Ville d’Ys were full and the cruiser ready to sail. Godhavn gathered at the waterfront, remembering the liveliness of the amiable sailors; and even little Eskimo boys, still rehearsing the leapfrog and tag they had been taught with much gesticulation and loud French shouts, had a glum look that the exciting farewell salvo of the shore guns could not erase. The guns of the cruiser boomed in reply; and as the Ville d’Ys arcked gracefully away in the direction of the fishing banks, the rails were crowded with waving figures, many perhaps as sorry to go as we to see them leave.

Thus passed our first week in Godhavn. Tea and coffee fests, a dance, the arrival of whales and occasional ships—all the summer variety of a northern port—punctuated my study of reports on the Upernivik district and Max’s exploration of the countryside. Once, characteristically, Max ventured so far that he was not able to return before the whole town was alarmed. I thought uneasily of the time when the weather would no longer be mild, but raging with blizzards; when I should have to sledge into the Devil’s Thumb country; when we should have exchanged this soft communal life for a solitary station beside the Great Ice; and I hoped that Max’s ignorance of fear would be chastened by that time. If not—Nature in winter Greenland is a mother that devours her own children.

One typical Godhavn day, cloudless and keen, while we were drinking coffee with Dr. Porsild and listening to Negro spirituals being played on his phonograph, there came an interruption in the form of the inevitable Eskimo small boy. A ship had come into harbor. The Hans Egede out of Copenhagen, three days ahead of schedule.

Too surprised to know whether that sinking feeling was excitement or nervous dread, I threw myself into the transfer of stores from warehouse to ship’s hold with furious blind energy. My friends, I avoided. It was best not to think of them until safely at sea. Untroubled ease was in any case over, and now it was necessary to turn my face to the future and responsibility.

Loading finished, leave-taking could no longer be postponed. The Governor, radio operator Poulsen, Dr. Porsild, and our many other firm friends, Dane and Eskimo, came and left. As I leaned on the ship’s rail and gazed nostalgically at Godhavn’s familiar houses, I winced at the realization that for me also it had become “home.” The Olsens, our “own” family, still lingered behind, displaying two of a Etter of pups, Max and Bill by name, to be treated impartially during our long absence. Would the ship never sail?

“Favell! Favell!”

The Hans Egede gathered speed, turning back into Davis Straits from whence it had appeared. Jagged headlands began to ghost by alongside. Here and there on the rock, like tiny patches of lichen, showed human settlements; and as we turned northward around Nugssuak Peninsula snow-covered peaks and valleys loomed gigantic behind them. It commenced to drizzle.

Chapter 3: Arctic Coal Mine

KUTDLISAT,” said Hans Ejornes, pointing ahead into the mist. Ejornes and his wife were the only other passengers aboard ship. The Swedish civil engineer had spent three years in the United States and spoke the language freely: in the few hours that Max and I had been at sea with him, he had become a sincere friend. It is often the case in sparsely peopled regions that men, having sized one another up, abandon the caution that renders friendship so slow a growth where human contacts are many, and human dependence upon a particular individual slight. Ejornes had befriended us, and we acknowledged our appreciation.

Now I sought to follow his directing arm. But I could see nothing. Cliffs and steep-walled fjords, their bays rugged with rock islands, showed intermittently through the fog with an etching’s delicate faintness, but of Kutdlisat itself no sign appeared. Even when the Hans Egede’s six hundred tons glided close in to the cloud-bank of cliff which mocked the water-beetle smallness of our ship with its echoes, the settlement remained hidden.

“What’s the town Eke?” demanded Max.

In her musical voice Mrs. Ejornes explained: “Kutdlisat is not Greenland. It is a mining town, a typical mining town; you have so many like it in the United States!”

Max looked blank.

Listening to the growl of drift ice scraping against the ship’s plates, thinking of the more than polar cold, of the immense ice dome capping all the island save its rim, I tried to picture a Minnesota iron-ore mining town in that setting.

“There.” Hans Ejornes pointed up an alluvial plain that stretched stepping-stone-wise to the base of the dimly seen white high valley beyond: “The powerhouse—you see the smoke?”

A puff of streaky brown against the pale expanse of background. Then powerhouse and high smokestack, rows of dull gray wooden cabins, tiny in the distance, electric power Unes, the two-storied houses of engineer and his assistant standing aloof, hills of coal dark beside a cleft embankment, rails leading down to a tramway overhanging the water’s edge, under which lighters could be freighted—all these bore evidence of an American mining town transplanted, or—what proved to be the case—of a town built all at once where no town had stood before.

The government, Ejornes informed us, had six or seven years ago decided to commercialize the old coal mine, previously worked in a primitive maimer. An engineer and a score of Eskimo families had been imported, together with lumber, electric drills, and other modern machinery. In a short time rose Kutdlisat, a new ‘lichen on the rock.’

I thought: Mongoloid Eskimos abandoning their pointed kayaks and the sea rich in fish and seals, to delve deep under ice-encrusted ground into the black, carbonized remains of florid plants that had flourished here many million years before, when Greenland was green and luxuriant with semitropical foliage. Then the ancestors of the present dwellers in a misplaced Minnesota shanty town were feeble insectivores scrambling timidly in palmlike trees halfway across the globe.... The picture grew too fantastic for the conscious mind to hold.

More than a little dazed by my reflections, I scarcely noted the preparations for landing.

Because Kutdlisat has no harbor, the Hans Egede was anchored a hundred yards from shore and coaling operations were started immediately. Big, double-ended flat-bottom lighters were loaded with coal and towed by motorboat to the ship’s side, where the coal was shoveled into wicker baskets which the Eskimos dumped by hand down chutes leading into the hold. It was a slow process. After watching awhile, Max and I went ashore on a returning lighter with lumber brought by the Hans Egede.

From the wharf we picked our way toward the mine through a litter of lumber, barrels of oil, packing boxes of all sizes and description, bales of clothing, and all manners of merchandise.

Close to the mine entrance stood a huddle of sod huts. These, I learned, belonged to those Eskimos who had fished and hunted in near-by waters from time immemorial, and who had fled to other regions with the encroachment of civilization.

A rumble and squeak of wheels announced the approach of tramcars from within the mine. Presently the laden cars came into view, pushed by stolid Eskimo women black with coal dust; human draft animals. I was not surprised at this, since in all Eskimo communities it is the women who labor, whether at preparing seal hides in traditional fashion, or serving as stevedores to passing ships. Our eyes followed their tireless bodies impelling the cars over uneven rails down to the water’s edge, where lighters waited to be freighted.

The mine proved to be much like others of its kind: gloomy, stifling with dust and foul mine odors. Splintery boards ready to burst under the strain were used for roof supports instead of the cedar posts demanded by safety, since all lumber must be imported from remote Norwegian forests. Eskimo men, dressed in typical miners’ outfits and covered from head to foot with coal dust, wielded picks and pneumatic drills, while their womenfolk loaded the cars and shunted them away.

Some of the miners had migrated to Kutdlisat from other parts of the country. Many of these were kayak hunters who had lost their skill in hunting. Not wishing to become dependent upon others, they had come to the mine for work. The natives of Kutdlisat, who were hunters and had not moved elsewhere with the opening of the mine, had lost the art of hunting, were no longer adept in their kayaks, and were absolutely dependent upon their ability to make a living shoveling coal. However, most of them still owned dogs and hunting gear, and sledging on the glaciers overlooking the mine was a popular Sunday pastime.

During the afternoon Max discovered an inflated ball in one of the government warehouses. “Hep!” he cried, forward-passing it to me.

I kicked it back. This was a pleasant diversion from our activities of recent weeks.

Moving further away, I sent him another to be scooped out of the air.

“Hep,” he grunted, returning it; and with him grunted nearly a score of grimy Eskimos gathered miraculously out of nowhere! The ball whizzed by my paralyzed fingers. When I retrieved it, Max grinned and winked. Thereafter we forward-passed in silence—at least Max and I were silent, though our audience continued grunting for us.

Before long the mine director hurried up, anxious to determine why the link between coal pits and stock piles had ceased to function. For a moment he gazed staring-eyed. Then, to the great glee of the football fans, he leaped between us to confiscate the ball! Thus did the Eskimos of Kutdlisat learn about football and football referees.

That night we stayed at the Ejornes’ comfortable home; and the next day, upon leaving, we received an invitation to visit them on our return the following spring. Warm hospitality on short acquaintance is typical of the country.

At sea again, we encountered the same fog that had haunted us ever since we left Godhavn. Max and I were now the sole passengers, so we sought out the officers of the Hans Egecle to learn what we could about them. Captain Breignhoffi a short, whiskered man of sixty-five, had spent most of his years at sea, and on the

Great Lakes waterways. Although my home is only eighteen miles from Lake Superior it was from Captain Breignhoff that I learned that Whitefish Bay, because of its frequent storms, is one of the most dreaded areas on any inland sea.

General Grant had been his hero since youth, although his faith wavered when a visit to the general’s tomb revealed the great man to be as stumpy in physique as himself.

Assisting Captain Breignhoff was Chief Mate Nordhoek. This modest gentleman was memorable to us because of his cosmopolitan background. Of Dutch parentage, he was bom aboard an English ship passing through a German canal, and was at present employed by the Greenland division of the Danish government. He owed his position largely to his record as skipper of the Godthaab in Lauge Koch’s 1929 expedition to explore the east coast of Greenland.

Second Mate Murk looked the personification of the old-time “salt.” Topping his six feet of rugged sailorman was a worn, flat-peaked cap, beneath which a badly scarred nose set between large, black sidebums failed to spoil a pleasing appearance. His ancient sea jacket seemed a relic of sailing-ship days. Yet Murk was no mere navigator, for his interest in botany had led to a collection of Arctic flora highly valued by those who were students of die subject.

Toward four o’clock my eye was caught by the massive outline of Kaersorssuak (Sanderson’s Hope) rising above a bank of fog, and later I could make out the peculiar hanging glacier that covered its crest like a little boy’s skullcap. We were nearing Upernivik.

The sea about us was now so thick with block ice that the Hans Egede slackened speed until it became difficult to discern progress by watching the cloud-hung shore. Max and I leaned over the rails, staring ahead into the obscurity which shrouded our destination. My thoughts pierced the fog. I saw myself in Upernivik’s winding paths, preparing to engage the services of a native family, buy additional supplies (coal, kerosene, butter, dog feed, dogs, and skins), make arrangements for transportation into the interior, write final letters home, check our supplies and see them safely on our next mode of travel. All this must be done quickly. Further loss of time after two weeks’ delay at Godhavn might be disastrous. Already the summer season was drawing to an end, and soon the chill autumn rains would merge into snow and sleet and blinding blizzards that must not catch us unprepared. Yet nothing could be done until the ship found her way through the fog to a landing.

The weather was characteristic of Upernivik. That town is one of the most northerly in the world, even closer to the pole than Norway’s Hammerfest. Our winter station on the ice to the northeast would be the veritable Ultima Thule. Only white bears and Arctic foxes habit that desolation—white bears, Arctic foxes, and the ravenous storms which go howling out over the entire northern half of the globe.

We waited for the enshrouding fog to lift, so that it was late evening before the Hans Egede dropped anchor. The following morning I was up and on shore before the unloading of the cargo had begun. Hurriedly I climbed over the rocky promontory separating the ship’s harbor from the town.

Upernivik straggles for a half-mile along a rocky peninsula facing the sea to the west. To the north and east it is protected from Arctic storms by a low hill, and to the south by the towering Kaersorssuak. The buildings are a huge church, a doctor’s ornate residence, the manager’s fine old home, the well constructed home of the priest and manager’s assistant, a store, a dingy hospital, and, unique in Greenland, a dance hall built by a colony manager as a memorial of lais affection for the natives.

Fortunately, I found Jensen, the manager’s short, round, jolly assistant, up and about. Sympathetic toward our needs, he was greatly helpful in expediting our purchase of kerosene, coal, and butter. Upon liis recommendation we decided to employ a native family and make final preparations at the small settlement of Augpilartok, twenty miles nearer the ice cap. The matter of transportation into the interior had not been settled and could not be, except by order of the manager. Tentatively we were promised the use of the Saelen, the colony’s motorboat, but only after the Hans Egede was ready for the return voyage to Denmark.

As little more could be accomplished during the confusion of cargo discharge, I controlled my impatience and joined Max at the dock. He was watching the clumsy twenty-foot fighters transfer cargo from ship to shore. Boxes, barrels, and lumber were swung aboard from the Copenhagen steamer, stowed roughly, and brought to land. There, sturdy women workers carried away immense loads on their backs, on stretcherlike frames; or, if drums of oil were to be moved, they rolled the great barrels before them. The men mostly contented themselves with working the lighters and burdening the women.

That day and the next, having finished checking our supplies on shore and making final arrangements for our departure, we waited impatiently for the word to proceed with loading of the Saelen. Time dragged on our hands; we were anxious to start on the final lap. Would the weather hold oute According to the statutes the Saelen must remain in harbor until the Hans Egede was ready to sail.

The second evening we were invited to the inevitable Greenland party. “Society” consisted of all Upernivik Danes and those from two visiting Royal Danish Geodetic Survey motor cruisers, the officers of the Hans Egede, Max, and myself. The atmosphere was very cordial. Outside, Eskimos crowded the windows to watch us laugh and joke and consume cake, apples and oranges, several kinds of candy, coffee, wine, schnapps, three varieties of French liqueurs, whisky and soda. Max, pragmatic, tried everything. Coming away, we were presented with four bottles of schnapps to be emptied January first in honor of Dr. Knud Rasmussen, the explorer. A staggering assignment.

The next morning we carried our personal belongings aboard the Saelen, the sixty-foot motor schooner we had been tentatively promised to take us to Augpilartok. This is an Eskimo community where recruiting was to begin. As our schooner threaded its way through the ice and out of the harbor, the Hans Egede gave us a last fav ell with three long blasts of her whistle. We waved back, but uncertainly, for the ship was soon lost to sight from our low position in tire fog, and our attention was occupied by the Saelen s whims and the constant threat of the ice which nudged and shocked from time to time. Low above the water, it was very damp and still. We felt as though we were hemmed in by the silence and the fog.

In about two hours run the boat swung hard over and pointed inshore, then coasted to anchor. From dun-colored skin shelters and sod huts Eskimos thronged down to greet us. I was favorably impressed with the appearance of these men, with their erect postures and their well kept clothing. Only the native trader stood apart, sullen and watchful. A harsh, unscrupulous bargainer, this Dahl resented contact with any who might hold him to account, and but grunted in reply to our skipper’s greeting. I was told that often Dahl knew no Danish at ah. Fortunately he was in a linguistic mood today, and consented to render into Eskimo the skipper’s interpretation of our English.

This determined, we proceeded up to the settlement, followed by as many of the curious as could tear themselves from the spectacle of the Saelen s unloading. Dahl’s “store” was to be used for recruiting. It was the largest of the score of sod huts and official buildings, measuring about twenty by forty feet. Max gazed about him with a rather incredulous air. He was more used to Detroit and Chicago department stores than to an Eskimo trading station, and did not know quite what to make of the barrels of rice, raisins, and hard sugar and the bits of colored cloth on the shelves. Shaking his head, he seated himself on a barrel, and the process of interviewing Eskimos began.

A suspicious-looking fellow would come before us, shy in his oily cotton jacket and worn sealskin trousers, and the conversation would proceed somewhat as follows: First, our question in English, then Skipper Saugmann’s Danish version of it, and finally Dahl’s Eskimo translation. The reactions of the man interviewed would then travel the reverse order: From Eskimo, to Danish, to English.

It was a little like telephoning Timbuctoo from New York, and seeing the operators of all intermediate nationalities “plugging in” until a reply came back over the circuit, while you wondered at the miracle of it. Once the message started speeding in the direction of my target, I had nothing to do but sit back and wait. Presently, like an alpha particle shot from an atom gun, the message jarred an answer from the villager.

Finally we engaged one Andreus Petersen and family as our helpers. “Andy” was a sturdy Eskimo, about five feet four inches tall, with an expression of a man who always sees the bright side of life. He would not deny the justice of his reputation as the best sledger, the best kayaker, and the best hunter in the settlement; and informed us as well that he was local representative in the native commune meeting regularly at Upernivik to decide local civic policies. The “gentleman from Augpilartok” was to receive 578 kroner—about $150—for these items:

The services of his wife Ewa, a seamstress of note.

The services of his aged mother Betsy.

The services of his seventeen-year-old son Axel.

The services of his fourteen-year-old daughter Susan.

The use of the men’s two kayaks.

The use of the men’s two dog sleds.

The use of the dory of Andreus’ own construction.

The services of fourteen sled dogs, which he must feed together with the rest of his family, since the 578 kroner included “extras” for that purpose.

As he translated the details of the agreement, our skipper looked grave. It was no business of his, of course, but we were overpaying—

You see, it was only for the winter’s duration that we were engaging this help.

The Saelen put out promptly for Proven when our business was completed. It was the wish of the Upernivik Bestyrer (manager) that we visit this community also, although we should have preferred returning without further loss of time. I fretted constantly. Were we never to get started? At Godhavn I had been shocked at the prospect of not continuing on to Upernivik in the Beothic; but that was long since, and the end was not yet in sight.

My emotions were far from amiable as we neared the small harbor beyond which the village of Proven blended into a background of reddish rock. Presently the red and white paint that proclaims an official building became visible; then the settlement flagpole, and the three pup-size salute guns, white-muzzled black barrels set on toy red wheels. To me all the gay red was the maddening color of official tape.

“Hi, Bill!”

Someone was shouting my name from the landing dock. Astonished, I looked at the waving figure. Nicolaisen, whom I had known at Holsteinsborg!

Nick, it seemed, was stationed there for the winter with his wife. She was a Pennsylvania girl who had come north three years before as companion to the wife of a Greenland official, and had Americanized Nick by a tour through the States during his leave of absence.

The warmth of their welcome, their baby daughter, Mona Lisa (whose smile was naughtier than her namesake’s), and the luxury of conversation in slangy American, reconciled me a little to the procrastinations of officialdom. As for Max, he exploited the Nicolaisens’ hospitality shamelessly. Tea in bed! Were these the rigors of life north of the Arctic Circle about which I had cautioned him? If so, he could endure them with the best!

My own enjoyment was tempered by gnawing anxiety. August 25th, fifteen days behind schedule, not one aerological balloon yet sent up, not even a decision made as to our station’s location. Always in the back of my mind there loomed a picture of our being caught by the impending rains: building under torrents of chill water, our parkas and undershirts drenched, our hands clumsy with cold and wet, footing treacherous, supplies ruined, no chance to become warm, to sleep dry, until the impossible task was completed.

The hooting of a ship’s horn announced the visit of the Hans Egede returning to Denmark. The evening was blind with fog. For hours I helped Nick load and fire the salute guns to guide the incoming vessel, until my head ached with the explosions and the ship’s continual dreary echo-soundings. Not until one o’clock in the morning had the Hans Egede passed through the shoals— despite the gloom, rocks were several times seen under the very hull—and into the channel. At three o’clock I dropped on my bed and slept.

Cargo discharge was completed by noon the next day. Still the ship did not leave. Had something gone wrong? No, the steamer merely awaited the arrival of the Bestyrer’s motorboat from Upernivik with some last-minute letters he wished posted.

“Imaka,” say the Eskimos, and Greenland Danes have adopted the word. “Perhaps.” A philosophy, imaka, a contempt for time’s mastery akin to the manana of Latin America; but to Max and myself, agonizing. For in the morning we were to get under way —imaka.

Chapter 4: To Work!

IT looks like a manure pile,” said Max.

I scoffed. “Your esthetic sense is dull; tins is good functional architecture, therefore beautiful to an unprejudiced eye.”

We gazed at the black and strawlike sod wall rising yard-thick about our shack, happy despite aching backs and sore hands because at last things were going right.

Luck had been with us ever since the Saelen dumped us and our stores on this stony islet of Natsiorsiorfik. It had not seemed so then, however. To find ourselves with all our possessions strewn on a hummocky rock at three-thirty on an Arctic morning was not stimulating, to say the least. Despairingly we had piled crates and boxes into three walls, thrown a tarpaulin over the top, and crawled into the hole like wounded animals.

But the next morning a perfect location for building was found not two hundred yards away. This was no small matter. The situation had to be such that it was sheltered from wind, yet exposed to the sun; near a hill suitable for balloon ascensions, but protected from snow slides; not too far from running water, and at the same time safely above the ice-thronged sea. What realtor would dare promise so much? Snug in a horseshoe of hills, the bend of which rose a hundred feet above sea level to provide a logical balloon ascension station, our dwelling site was unsheltered on only one side—providentially, the south. We should have the benefit of the departing sun to its last ray, and be ready to hail the prodigal’s return in February. Moreover, all about were tumbled boulders, some cottage-size, which would furnish additional protection from the wind. Thirty feet from our doorstep-to-be flowed a brook. No snow slide could deluge us from our collar of hills, for they sloped gradually. And supplies would have to be transported only a few hundred feet! The weather was immaculate. What terrible setback could be in store for us?

Our justified skepticism proved groundless, and we made rapid progress, working long hours from morning to night, most of the time in a twilight haze—though dawn and sunset still were more than twelve hours apart. Construction began as soon as our Eskimos had dragged our lumber the last short distance on its journey from Nova Scotian forests to the foundation of solid rock we had selected. We laid a double floor on a floor plan nine by fourteen feet. Separating this from the rock was a blanket of balsam wool over a six-inch layer of tundra insulation. On the 30th of the month, work began on the frames.

Meanwhile Max and I continued to live in the open, cooking over a primus stove when hunger could no longer be denied, and sleeping the sleep of the virtuously weary in our cave of boxes. Along with our work on the house we took scientific observations from the first day. Every two hours from eight in die morning until eight at night we dropped our tools to make observations. Max’s induction into cloud identification had started in Ann Arbor. Now we were recording clouds as to kind, amount, and direction. From them we moved to an improvised instrument shelter for a record of temperature, and a wet-bulb reading of the thermometer for temperature of the dew point, vapor pressure, and relative humidity of the atmosphere. Air pressure was recorded on a barograph, but, to keep an eye on the instrument, we soon fell into the habit of reading it at observation time. For wind velocity we relied largely upon our abilities of observation and former experience. Precipitation was noted as to amount and kind. Having made the last observation of die day, we would return to camp and pitch into construction work until long after midnight. Then, filled with satisfaction, we crawled into our box and tarpaulin cave.

I remember that ocean waves were washing over me in my dream when I awoke. It was undersea dark. The beating of waves could still be heard. For a moment I did not know where I was. Then I felt Max stir in his sleeping bag beside me, and I realized that torrents of rain were crashing down on our sagging cloth roof. I struck a match and looked at my watch. It was three o’clock. Runnels of rain spouted out from the box walls where my head had been, and only two yards away from my head the dogs were howling their protest against the downpour. I could picture them pressing their darkened fur against the lee side of boulders in a vain attempt to find comfort. Every day after sunset their weird concert began, but now they were outdoing themselves. It was the mournful voice of the northland.

Sleep would not return despite my weariness. My shifting about awakened Max—fortunately so, for his sleeping bag had settled into a foot of water. A cup of warm coffee would help, we decided. After much sputtering the primus finally decided to burn. Crouched in our cramped quarters, we fumbled about for a pan and cups. No fresh water! Max, already drenched, volunteered to get some. His appearance in the open brought a new chorus of complaint from the dogs. One beast, braver than the others, ventured to join me but was hurriedly induced to change its mind.

After what seemed hours we had the coffee boiling comfortably. As we finally prepared to settle down, another interruption —Andreus! The commotion or the smell of coffee (I think the latter) had awakened him. There was no room under the tarpaulin, so we passed a cup of coffee out to him. So happy was he about it that his whole family awakened to help adjust our sleeping quarters for greater comfort. Presently we were again ready to roll in. This time, Max, whose bag and clothes were soaked, stripped to join me in my bag. Thus we spent the night.

At eleven there were a few signs of clearing, but our hopes were soon drenched. Nevertheless, work went on. Between the heavier showers I put the anemoscope into operation, and anchored the theodolite on the hilltop, bracing its tripod with heavy stones to withstand the furious blasts from the icecap across the bay. Even in the rain that vast, unmelting dome of ice and snow, which promises to outlast mankind, as predicted in northland myths, loomed formidable and somehow sublime. It seemed a giant of primal antiquity, brooding patient in exile until time ripened for it to descend again upon our ephemeral human world. In Greenland it is still the ice age.

My task completed, I rejoined Max. Seeking to keep out the persistent rain, he had tacked strips of tarpaper over the roof, but through the unfinished windows and door drizzle still spattered in. The interior was dry by comparison with our sea cave, however, and we began the transfer of valuable supplies, together with our sleeping bags. A floor underneath, a roof overhead. What luxury! Beginning with that first night indoors, this isle of Natsiorsiorfik spelled home.

Next morning the rain and mist were gone. Overhead the sky showed brilliant with stars, for the sun was not to rise until six o’clock, and we set to work with renewed energy, hoping to finish our task before the advent of cold weather. We succeeded in tarpapering the entire outer shell of our double-walled house. In the rays of the rising sun the steel discs used to prevent nails from tearing the paper glinted splendidly against the dark background. Nothing but the promise of our initial balloon ascension could have tom Max away from his task.

Our aerological program was really die primary objective of the expedition. Next to observations of clouds, the pilot balloon is the least expensive and simplest method of sounding the upper atmosphere; hence, we were equipped to make a large number of ascensions—we had more than two hundred assorted red, white, and blue balloons and forty kilograms of calcium hydride.

Filling the balloon requires some delicate handling. The balance indicating balloon lift as it filled with hydrogen is managed with extreme care. The flight of the balloon from die hilltop is followed through the theodolite. At fifty-five seconds a buzzing warning signal comes from a timing device. Every minute at another signal the exact position of the balloon is determined and recorded. Then comes the final computation derived from the theodolite readings with the help of a plotting board in our hut. The aerological records were all made and computed along the approved lines of the United States Weather Bureau.

We took time off only to snatch a few mouthfuls of cold beans, pilot bread, and fruit. On the occasions when we had attempted to cook a formal meal in the open, half our energies were required to keep off the Eskimo dogs. They were intensely curious as well as permanently hungry. Nothing was safe from their raids, not even objects placed supposedly out of reach on the house roof, though once they had investigated anything they did not concern themselves with it again, provided they did not consider it edible —which classification did not exclude shoes, ham coverings of tar composition, and clothing.

During the afternoon we put finishing touches to the outer walls, while our Eskimo helpers packed dried tundra between the shells for insulation. But alas for romantic isolation! Andreus and his offspring, Axel and Susan, were not our only helpers. Though our station in this wasteland was north of the world’s most northerly settlement, precariously situated on the edge of an inferno of storms, to Max’s intense disgust kayaks paddled over every day from Augpilartok, fifteen miles distant. “Rubber-neckers!” he would murmur bitterly. This was not quite fair, since our visitors sought employment at the prevailing rate of three or four kroner a day in order to be able to buy sugar for their wives, and could not be blamed if there was not work for all.

One who found regular employment was Andreus’ old crony, Matti Hansen. Matti, of course, was unrelated to most Eskimo Hansens, this being a surname comprising half the native population, four-fifths of the remainder being Olsens, with a sprinkling of Petersens, Jensens, and other Danish “-sens” for variety. Our Mr. Hansen was my personal assistant, a specialist in wielding the saw. All day long he followed me about, alert for opportunities to exercise his profession, cherishing his chosen instrument, a ripsaw that behaved very poorly on wet lumber. It would have ruined anyone else’s patience to rip through a single board, but Matti sawed happily through hundreds of feet of wood, once measurements had been made for him.

Andreus, who was Max’s man Friday, was scarcely less devoted to the saw. However, Andreus was no novice. The twenty-foot wooden boat he had built for himself would have done credit to any carpenter, and had it not been for his timidity in offering suggestions he would have been the perfect helper. Like the rest of his people, he lost all initiative when dealing with white men.

His wife Ewa had been making sealskin trousers for Max and me while house construction was going on. I don’t know what the price of sealskin trousers may be in exclusive city shops, but including the price of the skins, ours cost us, complete, three dollars a pair.

We thought we looked very grand hi these sleek garments, with bright bandanna handkerchiefs about our necks. Despite inconveniences and slack standards in regard to meals, we were fastidious about our dress and our habits, brushing our teeth regularly, etc., and it is odd how much simple circumstances impressed the natives. Indeed, even the chaotic pile of painted wooden boxes excited far more interest and admiration than did our cameras and complicated meteorological instruments. This indifference to what civilized men most pride themselves on seems characteristic of primitive peoples. I recall that some years ago a Koloni-bestyrer of Godhavn escorted a young Eskimo girl visiting Denmark from the Copenhagen dock to her lodging, without eliciting more than a nod in response to his pointing out buildings, crowds, automobiles, bicycles, tramcars, and trees—all of which were as utterly new to her as to a stray from another planet. Unlike their inquisitive dogs, Eskimos have Ettle abstract curiosity. “Can use?” they ask.

September 4th the thermometer at noon registered more than fifty degrees. Sweltering in our heavy outer garments, we discarded them to work; then at once wished we had not. Hot sun and windless air had brought forth swarms of mosquitoes and buffalo gnats eager to sample imported blood. Our “family” dismissed the pests with casual waves of the hands, but Max and I were persecuted almost beyond endurance despite tobacco and frenzied semaphoring. Neither of us had thought to bring netting or repellent preparations: we were going to winter in Arctica’s most frigid region! Young Axel regarded us with a show of sympathy, but did I imagine that he muttered ‘too much bathe’? Certainly it was Max’s belief that characteristic Eskimo odors played no small part in discouraging insect enthusiasm.

Fortunately, my own work confined me to the house much of the time. I was building tables, desks, bunks, chairs, bookshelves, and equipment racks. When the stove and the remainder of our supplies were brought in, and we sat back cherishing our first hot meal in more than a week, we could survey our surroundings with justified approval. Until then I had never fully appreciated Walden’s charms for Thoreau. But the snugness of the dwelling wrought with our own hands, the clean boards, smells of fresh-sawed wood and tangy tarpaper, the cherry-red stove with its efficient draft, full bookshelves, supplies for belly and for work ranged round us where we could see them, made up an experience of complete, sensual satisfaction. We knew no wants. Mellowly I looked forward to my first real bath since Godhavn’s chilly tubs....

Chapter 5: Balloons, Graves, and Glaciers

THE balloon soared rapidly upward; and Max, unable to screw the vernier in order to follow the balloon, lost it from the field of vision.

“Release the vernier and point the telescope at it,” I cried.

The balloon was plainly visible, but Max’s actions were not quick enough; so I went to his rescue.

“I’ll point the barrel while you follow it in the field.”

“O.K. There it is! I have it again!”

Filling the balloon to its correct lifting power, following it through a theodolite, recording its position every minute, making all of the succeeding computations, and, in addition, performing all of the other tasks imposed by our meteorological program was no sinecure.

I prepared myself with the five-second warning buzz and made the reading at the full minute. When the ascension had been completed, the position of the instrument was again checked. Moving the theodolite and adjusting it daily in the cold winter would have been trying work; so we had anchored it and improvised a snug sailcloth covering for it.

“It’s not so easy as it looks,” he grinned, flinging nonexistent sweat from his forehead.

“You’ll get the hang of it soon.”

“I hope so.”

“All right. Now let’s complete the observation.”

As he took the temperature, humidity, pressure, and cloud readings, I thought of the time two years before, when I was the novice of the expedition, unable to send up a balloon without losing it. Max would leam. Indeed, he had to, for when I went north to study conditions in the Devil’s Thumb country he would be left to make observations alone.